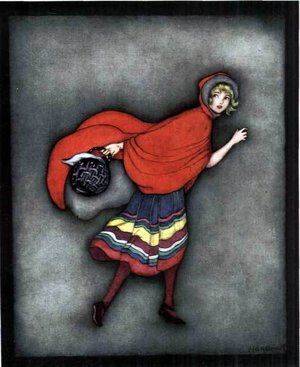

We all know the story of Little Red Riding Hood. A little girl goes into the woods to bring gifts to her grandmother, meets a stranger and tells him of her plans, the stranger turns out to be a wolf, the stranger eats the grandmother and waits for the girl. In more modern versions, a woodsman comes to the rescue and kills the wolf, rescuing the still-living grandmother and girl from inside its stomach. Older versions are various shades of gruesome. You probably heard this story as a child, and may have told it to your own children. If asked where the story originated, you would likely say something about the Brothers Grimm.

We all know the story of Little Red Riding Hood. A little girl goes into the woods to bring gifts to her grandmother, meets a stranger and tells him of her plans, the stranger turns out to be a wolf, the stranger eats the grandmother and waits for the girl. In more modern versions, a woodsman comes to the rescue and kills the wolf, rescuing the still-living grandmother and girl from inside its stomach. Older versions are various shades of gruesome. You probably heard this story as a child, and may have told it to your own children. If asked where the story originated, you would likely say something about the Brothers Grimm.

However, if you grew up in East Asia, you might have heard a version where a group of siblings are coerced into spending the night with a tiger or monster posing as a grandmother; in central and southern Africa, a young girl is tricked by an ogre imitating the voice of her brother. All of these stories share similar themes and subtexts, and the fact that they appear over and over across human cultures might speak to our universal human fears. Are these stories related? Do they share a common ancestor? How have they changed over time?

Studying the origins of folklore has often proven difficult, as oral traditions change drastically over time, with sections constantly being added or lost. In fact, you might say oral stories are the definition of “descent with modification”. Recently, historians and sociologists have begun utilizing techniques used in the study of evolution to try and track down the origins and evolution of our most well-known stories. A recent study published in the open-access journal PLoS One uses phylogenetics to try and find the answer to some of these questions.

Phylogenetic analysis was originally developed to examine evolutionary relationships based on shared traits. Here, the author uses traits such as aspects of plot, nature of the villain, nature of the protagonist, whether there are multiple children or just one, how the villain disguises itself, etc. to group stories together.

He found that the African stories are actually not of the “Little Red Riding Hood” type, but group together closer to a story known as “The Wolf and the Kids”. The East Asian stories do not group with either type, but instead represent a “missing link” that blends aspects of both the “Little Red Riding Hood” and “The Wolf and the Kids” groups. By applying a technique developed in one field to another, we may be able to answer outstanding questions across disciplines. If you are more interested in culture and history than in science, it might still pay off to pay attention in science class! (As a tangent, I should also note here that much progress in the study of animal behavior is owed to techniques developed in Economics.)

Fairy tales are not just ubiquitous across cultures, but they play into our everyday lives. Here at the University of Illinois, researchers in the department of business administration found that people describe their holiday shopping in terms of fairy tales. As they define it, “consumer fairy tales are narratives that are partially enacted in the marketplace, in which consumers employ magical agents, donors and helpers to overcome villains and obstacles as they seek out goods and services in their quest for happy endings.” In the quest for the perfect holiday, we apply narratives from fairy tales to our everyday experiences, creating villains and obstacles and envisioning ourselves as the heroes. Interestingly, the people who are more likely to describe their Christmas/holiday shopping in terms of fairy tales are those who strive to create a “perfect” holiday experience, and these are often the same people who apply a lot of time and energy into creating a “perfect” wedding or party.

And so, fairy tales have not only developed universally and spread and evolved across cultures, but it turns out we have a hardwired human desire to share our experiences in terms of heroes, villains, and triumphs. And, of course, to have a happily ever after.