Last week at the Ubben, Illini basketball coaches continued to drill small groups. Dominique Keller worked out with the guards, suggesting he’ll see time at the wing this year. Bill Cole continues to practice exclusively at the wing. Even Mike Davis occasionally drills wing skills; dribbling, running around screens, passing from the top of the key, running from particular spots on the floor to other assigned spots on the floor, passing from the wing.

Last week at the Ubben, Illini basketball coaches continued to drill small groups. Dominique Keller worked out with the guards, suggesting he’ll see time at the wing this year. Bill Cole continues to practice exclusively at the wing. Even Mike Davis occasionally drills wing skills; dribbling, running around screens, passing from the top of the key, running from particular spots on the floor to other assigned spots on the floor, passing from the wing.

Each player drills individually. Here, Keller dribbles under a scrim. This drill prepares players for facing triple-teams in which two defenders are stationary poles (Manute Bol, Les Jepsen) and the third a hovering carpet (Stacey Augmon).

Next the team broke into groups of three for offensive drills. And suddenly I found myself reliving past nightmares.

Next the team broke into groups of three for offensive drills. And suddenly I found myself reliving past nightmares.

In 2006, Dee Brown’s senior year, I puzzled at the stagnation of Bruce Weber’s “motion” offense. Many Illini fans did. The message boards featured numerous WTF! threads about passing the ball around the three point arc for 34 seconds before Dee launched from NBA range.

I suspect an unintended consequence of the motion offense derives from drills in which groups of players earn reward points for ball-movement, regardless of scoring. In these drills, Weber awards points for passes, deflections and the like. It’s easier to pass the ball around the arch than inside the lane. And thus a tendency develops.

Players are discouraged from standing still, and that tells us why Rich McBride continually ran his feckless route along the baseline. “Where is he going?” you wondered silently, to yourself. “Where is he going!” you screamed at the teevee after a few cold ones.

The answer, it turns out, is both nowhere and anywhere. Just so long as the ball moves, and nobody is standing still. If the drill required three passes and a basket within 12 seconds, you’d see an entirely different set of instincts come game time.

Another aspect of these small group scrimmages that manifests itself in game situations: players are discouraged from dribbling. In the individual drills they dribble. But once they go three-on-three, etc. any pass is preferred. I have to assume that this stifles an instinct toward dribble-penetration. I also assume that Bruce Weber is smart enough to recognize that consequence. His winning percentage is better than mine. It must be a part of the grand plan.

The stagnant motion disappeared last year, but the reluctance to shoot the ball remained. So we saw a lot of passing, and still no buckets. Atrocious final tallies of 36 and 33 points thrilled Midwestern soccer fans, who hate scoring.

Weber may be as surprised as anybody, because we know that he tells players to keep shooting. He told the Final Four squad to keep shooting when they were having doubts. Bruce Weber has been telling players to keep shooting practically since he arrived on campus.

But before a player can keep shooting, he has to shoot. So when?

The theory behind Weber’s regimen is that opposing defenses will tire after chasing Illini around the court for 34 seconds of each possession. But opponents may have it figured out: They don’t need to do anything for the first 15 seconds.

Maybe this year, Weber will surprise everybody by attacking the basket immediately. It could happen. One of Bruce Weber’s greatest attributes is that he learns, and evolves. After parlaying a Final Four run into the recruitment of gridder C.J. Jackson and grappler Chester Frazier, Weber changed his tactics. This year, after digging a 14-point hole against Northwestern on my birthday, Weber heeded Wayne McClain’s counsel to press the Wildcats full-court. The previous year, Weber heeded McClain’s demand to start Demetri McCamey, the guy whose last second shot beat those Wildcats.

The motion offense is chess. It really is. And like chess, players with lots of experience do much better than players without. It can be aggravating at times, but it’s less painful to watch than that forced, telegraphed pass to the post which seemed the singular component of Bill Self’s Hi-Lo.

Just my take. I could be wrong.

FRESHMAN’S FRESH LEGS

FRESHMAN’S FRESH LEGS

DJ Richardson runs effortlessly. In wind sprints, his light bounce and explosive propulsion draws attention to the strain required from others. You see them working, you see him gliding. It’s weird.

In fact, “explosive” is a bad adjective, because an explosion draws attention to itself. In DJ’s case, it’s not like that. You weren’t aware that he moved. He’s just not there anymore.

And then he looks back, feels bad for the other guys, and lets them catch up a little. Smells like team spirit.

FRESH MAN, MENDING LEGS

FRESH MAN, MENDING LEGS

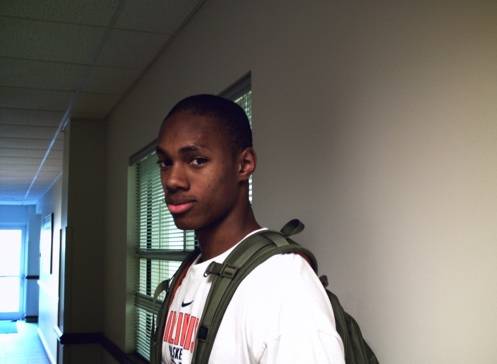

While everyone else drilled and scrimmaged, Joseph Bertrand biked a few miles on the stationary cycle, keeping his knee loose following arthroscopic surgery. Bertrand took some weight off his knees by chopping off his curly locks, revealing a shorn scalp for the first time since puberty. It turns out that maintaining corn rows takes a lot of time, and so does the scholar-athlete gig at a Big Ten school.

When confronted with a decision between the two, Bertrand gave up the braids.

CRANDALL’S BUSTED LEG

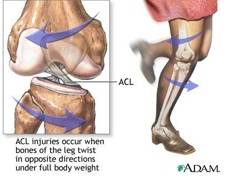

Crandall Head is following  Steve Bardo’s path to success. Bardo prepared for four glorious years at Illinois by breaking a leg and missing his entire senior season at Carbondale High. Head will sit out his senior campaign at Rich South while his anterior cruciate ligament mends.

Steve Bardo’s path to success. Bardo prepared for four glorious years at Illinois by breaking a leg and missing his entire senior season at Carbondale High. Head will sit out his senior campaign at Rich South while his anterior cruciate ligament mends.

Here’s Crandall in simpler times, when Joseph still had hair.