The past two weeks have brought the first flush of this year’s spring — steady rains, then hours of sun; dandelions, flowering trees, and deep grass that needs mowing. Lilac blossoms scent the city; they bring to my senses the six or eight lilac bushes that marked the border between our drive and the neighbor’s yard when I was a kid. Thick as trees, these large, old plants bore enough fruit to overwhelm the whole neighborhood.

The past two weeks have brought the first flush of this year’s spring — steady rains, then hours of sun; dandelions, flowering trees, and deep grass that needs mowing. Lilac blossoms scent the city; they bring to my senses the six or eight lilac bushes that marked the border between our drive and the neighbor’s yard when I was a kid. Thick as trees, these large, old plants bore enough fruit to overwhelm the whole neighborhood.

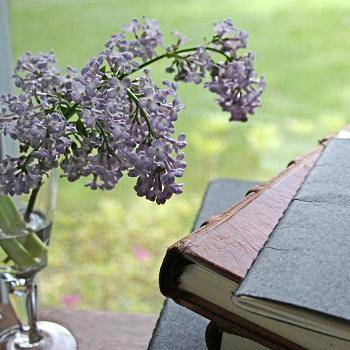

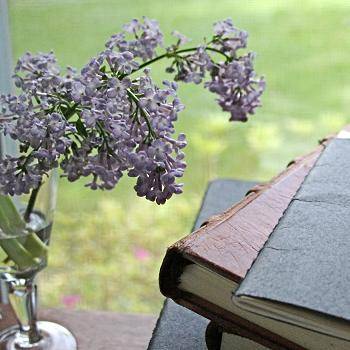

So I’ve clipped a sprig of lilac from some stranger’s yard and put it in a glass of water on my desk. I’ve found and unfolded a birthday letter from my father, written in 1987 when I turned 21. “I remember the April morning when you were born,” he wrote. “I came out of Carle Hospital and the streets were wet from rain. It was a perfect day.” If I could just stay in my little perfumed, nostalgic world.

But before the sentiment can fully settle on my desk, I remember my father’s end-of-May death at 59. After a pulmonary embolism killed him, my mother and I walked out of Bro-Menn Hospital into idyllic, even mythic spring weather and sunlight. We wandered around for a while. We couldn’t find the car in the parking garage.

I sit here and slice open the lilac blossoms with my thumbnail. Or I crush them like little glands between my fingers until they stink. I remember how the wide, tongue-shaped leaves of the plants will mildew and molder in summer heat. I think about how Whitman spread the fragrance of “Lilac blooming perennial” around his elegy to make Lincoln’s death more bearable.

Like a Central Illinois spring, memory proves to be unsteady, equally lush and harsh. “April is the cruelest month,” writes that old Midwestern poet T. S. Eliot, “breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land / mixing / Memory and desire, stirring / Dull roots with spring rain.” Eliot preferred stasis and hibernation to resurrection. All the coursing water in the stems of plants, and all that coursing blood in the body, all that desire and hope lead to nothing that can last.

From the time I was 6 or 7, my job on spring and summer Saturdays was to pull up weeds and grass from our gravel driveway. I’d crawl on my hands and knees in the matted down rocks and pull the weeds by hand, or dig them out with a dulled kitchen knife. Fingertips would bleed and bruise a bit. Rocks would impress little maps on my bare knees. Without a shirt in late June, my back and neck turned red. By July, I was browned and immunized against sunburn.

In April and May, though, I liked this weird work. While the neighbors watched through the lilacs, I made determined faces and filled a sand pail with weeds. I would pour them into a pile on the porch to count at the end of the morning. I got paid two-cents a pull, and I rounded up. My father paid in cash, enough to offset my resentments and ripped up knees. Sometimes he would crawl around in the rocks with me and contribute his weeds to my pile. And when the lilacs died, the stones of the drive would be covered in purple for a time.