In Losing my reality, pt. 1, I discussed how recent advances in information and communication technology pose a threat to certain aspects of our lives. This concept came from a recent project I did for a class at the U of I last fall; the project was a video called “Technological Dependence.” For this video I decided to take a week break from cell phones, computers, and television.

In Losing my reality, pt. 1, I discussed how recent advances in information and communication technology pose a threat to certain aspects of our lives. This concept came from a recent project I did for a class at the U of I last fall; the project was a video called “Technological Dependence.” For this video I decided to take a week break from cell phones, computers, and television.

However, throughout my week I often slipped up (sometimes without even noticing it) and used these devices. If nothing else, it became obvious that the connection between my daily life and these forms of technology were blurred together so completely that it was unclear what constituted as breaking my experimental promises. Was I no longer able to use the intercom to get buzzed up to my friend’s apartment at Burnham 312? Could I sit in Murphy’s with the TV in my peripheral vision while hearing the sportscast? What about my everyday classes . . . could I even attend knowing that they use a computer and projector? How could I do my homework . . . what would I do in an emergency?!

When I realized how difficult it would be to keep in touch with friends, do assignments, and go to class, I decided that I might as well just forget about cutting those devices out of my life completely. They were ingrained into my daily life, and unless I had some sort of religious excuse, would not be able to pass some of my classes or maintain a friendship without them.

That was December ‘09, and fittingly, as I write this article, I have just come back from a vacation at the Yellowstone National Park, where cell phone service and Internet are rare. Coincidentally, I also lost my phone on this vacation (check again, Best Western). However, I had no difficulties adapting to these changes, be it because I had lived through it before or because it afforded me the opportunity to truly experience my beautiful surroundings.

Yet throughout the week, I noticed something I may have otherwise been oblivious to; I realized how important cameras seem to be on vacation. Most were digital, some were film, but it was obvious that the majority of people were looking at amazing sights they had traveled thousands of miles to see through a camera lens. Why? Do we rely on these pictures and videos to remember what we “witnessed?” Are we all practicing a type of delayed gratification — wanting to be able to look at these pictures at work, bringing ourselves back to the moment they were taken? Or perhaps we use these photos as “proof.” Proof that we were there, and that we have experienced something great. Suddenly these photos become a part of us. They are a kind of evidence that we exist, that we can appreciate, and that we understand the rule of thirds.

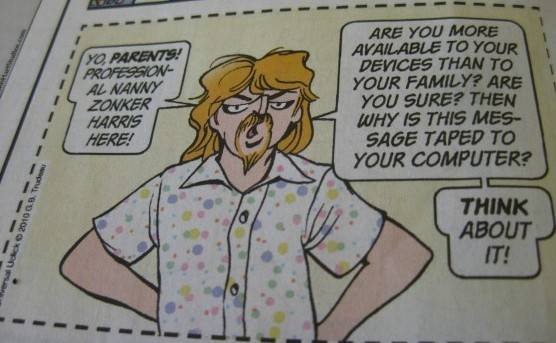

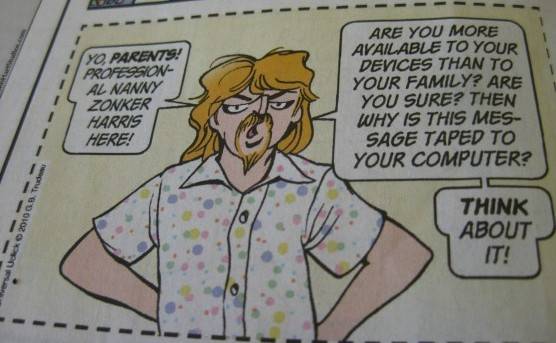

There’s no turning back now, we became caught up in a self-fulfilling concept of “the future” that is inseparable from technology, and now we can’t live without it. It has become a part of us, much like the pictures we take on vacation. Our smart phones are our new windows into the world, soon to be replaced by new, smarter phones. With these devices, we are now connected to each other 24/7, with no excuse for not returning calls or emails. We are not directly responsible for keeping information or getting in touch with our peers; that responsibility has been passed onto our new technology. And though I don’t know what it’s like to have the level of responsibility shared by many professionals (be they teachers, doctors, attorneys, etc.) I have heard that it can get quite daunting having such efficient technology as email. People are held to an expectation that they will be available at all times to return messages. There is no excuse . . . unless, of course, you lose your cell phone in Yellowstone.

Feature image from studentlife.univ.edu