I am embarrassed to admit that I encountered Joan Didion for the first time this just past winter, when I read Slouching Towards Bethlehem over the Christmas holiday. Of late, I find myself returning to the essay “Can’t Get That Monster out of My Mind” from that volume. Reflecting on the tension between artistic license and commercial viability, Didion invokes the novel, characterizing it as “nothing if it is not the expression of an individual voice, of a single view of experience.” The line resonates because I have been working with a literary form even more personal and individualistic: the zine.

Photo by Michael O’Boyle.

For the uninitiated, I do not believe I can give a satisfactory definition of the form. After spending the last three or so weeks looking through the Independent Media Center’s Zine Library, I share scholar Stephen Duncombe’s inclination to hand over a stack and say, “These are zines.” Any attempt at a firm characterization could be easily refuted with dozens of counterexamples. They are small volumes of fiction, nonfiction, polemics, poetry, journal entries, or any form of written content, except art collections and comics. They are the work of one creator, except compilations and those which accept general submissions. They are handmade, except those professionally printed. They are created around subcultures and underground music — especially punk rock — except those which exist on literally any other imaginable subject.

The closest thing to a unifying feature is that they are emphatically amateur: their creators, known as zinesters, practice their craft without expectation of circulation, acceptance, or payment. They do not bother with the approval of an editor or consumers to share their content. They often craft their volumes at a financial loss and release very small quantities to immediate acquaintances. They pride themselves on working outside the mainstream and creating without regard for marketability or even accessibility. They may not have something worth sharing, but they have something worth saying. Zine making is anti-establishment, anti-Capitalist, and anti-anything-else-you-can-think-of.

Photo by Michael O’Boyle.

As an aspiring writer who hopes to join the establishment, this baffled me when I began looking through the IMC collection. A central idea in the very small amount of formal training I have received is that we write for an audience. Even in personal essays, memoirs, and published diary entries, which detail the most private of thoughts, writers believe they have something valuable to general readers, so they polish their work to a “consumable” form. Zinesters defy this maxim. Pouring over the IMC’s perzines (a portmanteau of personal zine), I encountered unintelligible rants about incidents while grocery shopping, narratives of unrequited love, open letters to Britany Spears, and drawings which so grotesquely distort human anatomy I may have nightmares in the coming weeks.

Photo by Michael O’Boyle.

Some contained reviews of other zines and interviews with rock bands, but the majority are understandable only if the reader knows the zinester’s personal history. And personal does not mean good. I include the Didion passage for what follows it: a novel is “nothing if it is not the expression of an individual voice, of a single view of experience — and how many good or even interesting novels, of the thousands published, appear each year?”

Photo by Michael O’Boyle.

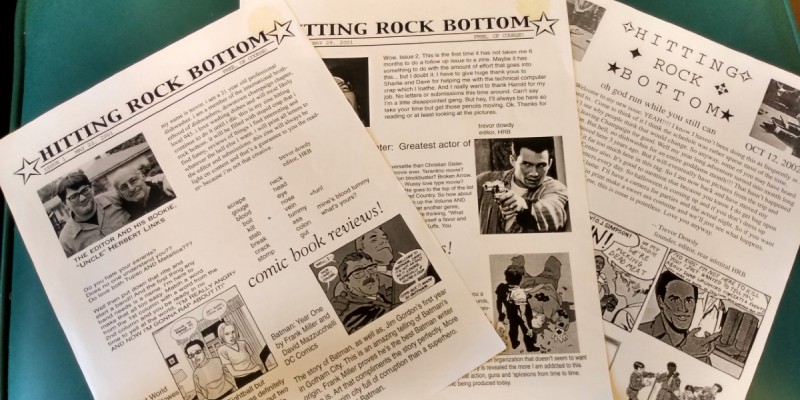

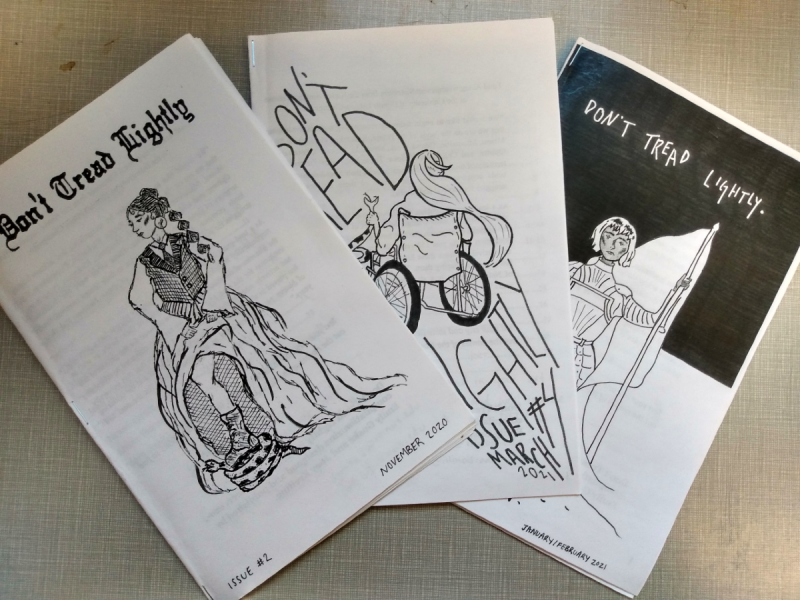

Still, a few of the hundreds if not thousands of volumes I considered tickled me. For instance, Trevor Dowdy’s Hitting Rock Bottom, wherein the creator’s life as a professional dishwasher in downtown Champaign and comic book aficionado is chronicled. Aside from the ability to carbon date it by references to Radio Maria and The Great Impasta, I was captivated by Dowdy’s sarcasm. He tells us he is a card-carrying member of the International Brotherhood of Dishwashers, Local 945. His professional pride shines through, guaranteeing his dishes are always clean enough to eat from. He reveals his refined artistic instincts by declaring Christian Slater the greatest actor of all time. Another favorite is Don’t Tread Lightly, a “feminist, queer, eco-compilation zine” produced by students at U of I. Issue #3, from January/February 2021, contains Emily Guske’s drawings of the women present at the Biden-Harris inauguration titled “Coats of the Inauguration 2021;” the surprise at the final drawing being the iconic Bernie-in-mittens made me laugh out loud.

Is this the reason to create something so populistic it ironically excludes a vast majority of the population? A zine titled Personally Yours… Life on Zines shelved at Ricker Library contains zinesters’ reflections on their craft. Liz Mason quotes Tim Kreider describing zine making as “radioing messages into interstellar space: more a gesture of faith than anything else.” A zinester known as Galia describes the communal sense she feels by creating: she describes the experience of going to zine gatherings where “girls who reminded [her] of [herself] picked [her zines] up and read them and said things like ‘thank you, this is so real.’ [She] felt seen and heard.” I suppose the off chance of reaching another human is reason enough to create.

But the real rewards seem to be pure, unrefined expression, the satisfaction of crafting something with one’s own hands, and a channel for creative outlet. Dowdy states that “When [he] first picked up HRB, [he] was a loser. [He] drank all day long and smoked 3 packs a day … [his] life is on track now … when [he thinks] about all that Trevor Dowdy and HRB has done for [him, he gets] a big HARD ON!!!!! [sic]” The long tradition of irreverence in zines notwithstanding, Dowdy’s zine allowed him to create something that is completely his own, a cultural space where, unlike in the “real world,” he is never a “loser.” This is the magic of zine making.

The value to the creator is at the expense of the potential reader, though. Zinesters purport to create community, but their zines are virtually inaccessible to those outside their circle. To find a scene, you have to know where the scene is. It is easier in larger cities — Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Portland, and the like — and the usual suspects are well represented in the IMC collection. However, I can count the number attributed to Champaign-Urbana residents on one hand. To be fair, the IMC was only founded in 2000 and the collection goes back about that far; the simplest explanation is the underground migrated from printed zines to blogs and Myspace pages around that time. Even so, the problem of knowing where to look is only amplified in the online world.

Besides, merely having a presence online places you on the grid and makes you just another data point to be classified and marketed to. Zines at least preserve the core of underground culture: existing outside of mainstream recognition and thus beyond the reach of Corporate America. I suppose obscurity and inaccessibility is the cost. In that regard, we are fortunate to have the IMC Zine Library (and U of I’s own collections scattered across several libraries), where we have a trail, if not a doorway, to the scene.

The IMC Zine Library is open to the public whenever the IMC is. A special thank you to the IMC staff and the Art and Architecture librarians at U of I for their invaluable assistance and generosity as I researched this piece.