When it was conceived a year and a half ago, the Planet U conference set for itself perhaps the great task of academic discourse in this century: “The goal of the conference is to stimulate dialogue between various academic disciplines in their research on climate change, and to encourage more effective communication between the academy, the media, and the general public.”

When it was conceived a year and a half ago, the Planet U conference set for itself perhaps the great task of academic discourse in this century: “The goal of the conference is to stimulate dialogue between various academic disciplines in their research on climate change, and to encourage more effective communication between the academy, the media, and the general public.”

These efforts toward interdisciplinary research and conversation are trying to span a great chasm between the sciences and the humanities.

The listed speaker to welcome the conference participants was Steven Sonka, the Vice Chancellor for Public Engagement. He did speak, if you wish to call it that, mouthing the bloodless encomiums typical of university administrators who are careful to say as little as possible and offend no one.

Far more interesting, however, was the unofficial welcome given by Gillen Wood, Associate Professor of English and one of the organizers of this conference. He began with a statistic: 98% of scientists believe in the existence of anthropogenic climate change. A bare majority of the American public believe the same, and the trend is in the wrong direction.

Wood attributed this to a massive public relations campaign by polluting industries, a “triumph of disinformation”. Aiding in the construction of a political coalition to educate the public, reverse this trend and pass legislation to restrict carbon emissions is, in his opinion, a prime goal of this conference. Wood then introduced the dance performance commissioned from Illinois faculty member Jennifer Monson and performed by her and students Kyli Kleven, Stephen West and Jennifer Allen.

I am no expert on experimental dance. The best way that I can understand it is through analogy to the art of Jackson Pollock. If you wanted him to draw you a picture of a tree or a bowl of apples or a nude woman, you’re SOL. It’s just not what he did. Pollock’s art does not operate in terms of one to one representation of objects in the external world. It has its own internal structures and logic which are available to careful observation but cannot be understood with reference to anything outside the work of art itself.

For this reason, asking Monson’s style of choreography to answer to this particular purpose, opening a conference on climate change, seems odd to me. It seems better suited to be presented on its own in a recital where it can stand or fall on its own terms. Frankly, I don’t know what to make of the piece. It took me a long time to understand what Pollock was on about, so I will certainly seek out more of her work, but I’m not sure what to say. Monson was kind enough to give me some of her time after the piece and spoke about a rough equivalency between the layers of the atmosphere and the verticality of the body as a starting place, but if it was there, it was transformed beyond my ability to recognize it.

Brian Fagan delivered the keynote lecture, ”The Silent Elephant in the Climatic Room,” in a commanding performance. Professor Emeritus at UC Santa Barbara, his decades of experience teaching anthropology were apparent. His visual aids were clear and piercing, using striking photos and a minimum of text. Fagan’s Received Pronunciation is tinged with that slight movement of “r” toward “w” that reminds me of Sister Wendy.

Brian Fagan delivered the keynote lecture, ”The Silent Elephant in the Climatic Room,” in a commanding performance. Professor Emeritus at UC Santa Barbara, his decades of experience teaching anthropology were apparent. His visual aids were clear and piercing, using striking photos and a minimum of text. Fagan’s Received Pronunciation is tinged with that slight movement of “r” toward “w” that reminds me of Sister Wendy.

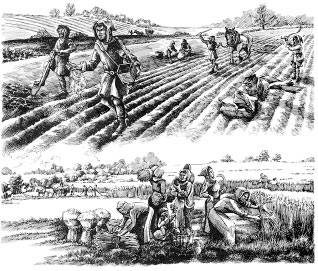

He began with an evocative description of life for the subsistence farmers of the Zambezi River Valley at the end of the dry season. The heat is unbearable, 105 degrees and above in the shade. Farmers set fire to the brush in their fields and work the ash into the soil to improve its fertility.

The tension builds. Everyone is waiting for the rain. People become short with each other. Fights break out. Finally, a shower comes. No matter how long it lasts, 20 minutes or all day, the farmers plant their seeds. They are at the mercy of the rains. If they come, the village will eat and survive. If they don’t, hunger sets in by Christmas. If living paycheck to paycheck sounds bad, imagine living harvest to harvest. Drought — no phenomenon associated with climate change receives less attention or has greater impact.

Fagan’s most recent work has focused on the Medieval Warm Period, a “rather ill-defined” period which lasted from approximately 900 to 1300. The temperature across Europe rose a few degrees and improved the weather, especially the critical period in late summer when the crops are ripening. While the Medieval Warm Period brought benefits to Europe, it devastated arid regions over much of the rest of the world. Chaco Canyon, where the Pueblo people built their Great Houses as centers for religious ceremony, was completely abandoned by 1190.

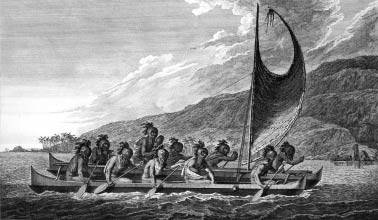

Unpredictable rainfall made it untenable. The litany of droughts during this period went on — Palmyra Island in the South Pacific, Tiwanaku on Lake Titicaca, Wanxiang Cave in northern China. We need to learn more about how cultures reacted and adapted to these dry conditions, because droughts have returned. The total amount of drought has increased 25 percent since 1990. Extreme drought conditions will cover 30 percent of the world in 100 years, up from three percent in the present day. 130 million Asians will suffer food shortages by 2050. It will not be possible to grow wheat in Africa by 2080.

One of the things we know about drought is that people migrate en masse. Movement away from regions that were too dry was part of the planned adaptations that the Pueblo in Chaco Canyon employed. They maintained kin relations with tribes in wetter areas in order that they’d have a place to go. What, Fagan asks, will we do with people from Central America if they suffer extended droughts and migrate north? What will we do with people from Phoenix, Los Angeles and Las Vegas, for that matter? We know that droughts of 200 years are possible in California. Despite these prognostications, Fagan ended on a hopeful note, rooting his optimism in Homo sapiens’ ability to adjust, to improvise, to plan ahead.

One of the things we know about drought is that people migrate en masse. Movement away from regions that were too dry was part of the planned adaptations that the Pueblo in Chaco Canyon employed. They maintained kin relations with tribes in wetter areas in order that they’d have a place to go. What, Fagan asks, will we do with people from Central America if they suffer extended droughts and migrate north? What will we do with people from Phoenix, Los Angeles and Las Vegas, for that matter? We know that droughts of 200 years are possible in California. Despite these prognostications, Fagan ended on a hopeful note, rooting his optimism in Homo sapiens’ ability to adjust, to improvise, to plan ahead.

The Planet U conference moves from the Illini Union to the Beckman Institute tomorrow and Friday. A full schedule is available here. I would recommend Calvin DeWitt’s talk at 4 p.m. I’ve heard him on the public radio program “Speaking of Faith” and he is a penetrating thinker, trying to understand environmental responsibility within the context of evangelical Christianity.