Editor’s Note: With permission, we are republishing Will Leitch’s recent newsletter entry, originally entitled “Candyfloss”, here on Smile Politely. Subscribe to his newsletter on Substack.

The first thing I remember that ever made me cry uncontrollably, deep heaving gulps of tears, was the 1983-84 Illinois Fighting Illini basketball team. Specifically, that team’s 54-51 loss to Kentucky in the Elite Eight, at Rupp Arena, back when teams could play NCAA Tournament games on their home courts. That was a great Illini team, with Bruce Douglas and Efrem Winters and Doug Altenberger and George Montgomery, and they’d made a rush through the tournament that year, beating Villanova and Maryland en route to that matchup with the No. 3 Wildcats, a team with Kenny “Sky” Walker and center Sam Bowie, who, two months later, would be drafted one spot before Michael Jordan.

I was seven years old and only recently obsessed with sports, and as much as I loved Ozzie Smith and my St. Louis Cardinals, Illinois basketball always hit closer to home. The University of Illinois was only 45 minutes away from Mattoon, where I lived, and the local CBS station, WCIA, showed every Illini game live, preempting whatever national programming that might have been on the time. (I talked about this phenomenon with Illini Board’s Robert Rosenthal on his podcast this week.) This led, I’d argue, to a Central Illinois-wide obsession with Illinois basketball that is so powerful still today, and it made me think that every Illini game was the biggest, most important thing that had ever happened. I loved that team and didn’t think they could possibly lose. And then that game. They had Kentucky on the ropes late, but, in front of all those Kentucky fans, referees missed an obvious traveling call on the Wildcats’ Dickey Beal (even Sports Illustrated called it “Kentucky’s home cookin’” at the time) and next thing you knew the game was over and I lay on the floor of my parents’ bedroom, the only room with a TV, and wailed and wailed and wailed. My mom thought there was something wrong with me. She was right.

Sports — for the obsessives, a group I quickly realized I belonged to, as I lay weeping on a shag carpet floor in a rural Illinois township in April 1984 — are stupid and cause nothing but pain. Until they don’t. Your team surely does the same to you. Our teams do the same to all of us.

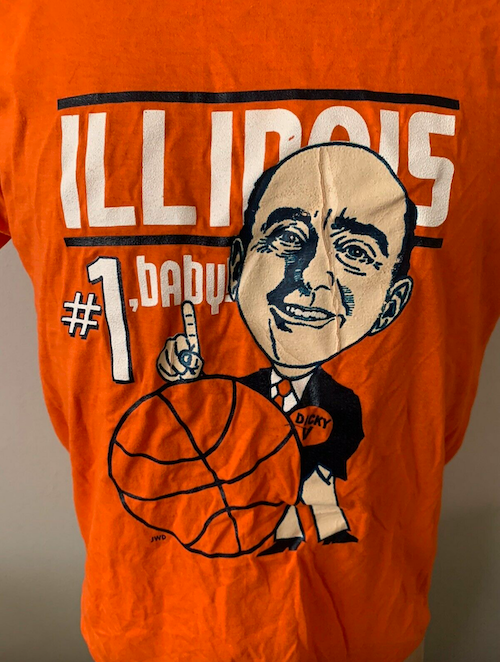

More than the Cardinals (whom I’ll admit I briefly lost a little touch with when I was in college, in Champaign), more than writing, more than even my closest lifelong friends, there is no more central organizing principle of my life than Illinois men’s basketball. Lou Henson was just getting started in 1984, and he built a machine that reached eight consecutive NCAA tournaments from 1983-1990, the exact years in which sports were most important to me. I threw a shoe against the wall when they lost to Austin Peay, hugged my father (something we never did, and still really don’t) when Nick Anderson hit that 3-pointer against Indiana, was 13 years old, just the perfect age, when that Flyin’ Illini team with Anderson, Kendall Gill and Kenny Battle took the nation by storm before falling in that cruel Final Four loss to Michigan. There is a class picture of me in the seventh grade wearing a T-shirt I bought at the local IGA with a drawing of Dick Vitale, holding his finger in the air, saying, “Flying Illini No. 1 Baby!” You can still get one of these on eBay, and I would like you to buy it for me for Christmas.

Photo image from eBay.

I applied to two schools out of high school: The University of Southern California (because my friend Tim was going there, and because I liked movies) and the University of Illinois, and there was never really any doubt where I was going to go. My first assignment for the Daily Illini (and my first byline ever outside the Mattoon High School newspaper and the Mattoon Journal-Gazette) was to cover a fraternity basketball game coached by Illini guard Richard Keene. (I was 17 years old. He refused my request for an interview.) I ended up covering the team for the paper, had dinner with Lou and Mary Henson at their home and drove all the way to Albany, New York, in the Daily Illini Nissan, only to watch them lose to Tulsa in the last NCAA Tournament game Henson would ever coach. I was (very) occasional drinking buddies with Kiwane Garris, Matt Heldman gave me his Econ 104 notes, Chris Gandy was high school buddies with my college girlfriend. Being this close to the Illini blew my mind. It made me feel more successful and more important that I had ever felt before and honestly have ever felt since. Illinois basketball was the center of everything. To be close enough to feel its heat made me wonder if maybe I’d already accomplished everything in my life that needed to be accomplished. You can see how college towns can become too closed off, too reverent of their sports heroes. In that tunnel, it can become all that matters.

I moved away from the Midwest in January 2000, and in many ways, Illini basketball became the one portal I had for an instant virtual trip home. I was as connected to Illinois basketball as I ever had been after I left, from the Bill Self era to Bruce Weber to that wonderful Dee Brown/Deron Williams/Luther Head team, whose games I made sure never to miss, even if I had to harangue various bewildered bar owners on Smith Street in Brooklyn to turn the games on for me. I remember, at the under-three timeout of the Elite Eight game against Arizona in 2005, at the old Camp Bowery headquarters in New York, I called my father back in Illinois. We have a tradition, when the Illini lose their final game, of saying, “well, looks it’s time for baseball season.” (We do the same thing when the Cardinals lose their final game: “Looks like it’s time for basketball season.”) Illinois was down double digits, with just three minutes left, the end of the most memorable season in Illini basketball history, falling just short again.

“Shit,” I said.

“Just wait,” Dad said, always still believing. “This ain’t over yet.”

And then of course this happened.

My dad ended up retiring and going to a ton of Illinois games now that he had time: It’s all he’d ever really wanted to do. It also led to this wonderful moment of my father not realizing he was wondering into a live show on the Big Ten Network.

(He’s lost some weight since then.)

And I now go back every year, or I did until the pandemic, to catch an Illini game, which is of course just an excuse to get to go home, to be home. Heck, I even pulled some strings and got to hang out with the Orange Krush one time.

Photo provided by Will Leitch.

It’s a little bit absurd to still care this much about college basketball. The sport itself is inherently corrupt and perhaps in a death spiral, or at least in serious existential peril. It’s dumb, even immature, to be this invested. I spoke to a class of Illinois journalism students a few years back, and then-current Illini point guard Jaylon Tate was in the audience; it occurred to me as I talked just how much, in the privacy of my own home, I had screamed at him and for him (but mostly at him), and how silly and even a little deranged it was for a grown adult to have so much emotional expenditure in, as I could now see in that class, simply a young college kid. I am now 23 years removed from college myself, old enough to be the parent of all of these players. The star recruit on this year’s team is Adam Miller, who scored 28 points in the opener against North Carolina A&T and was born on January 23, 2002, which is so insanely recent I’m pretty sure January 23, 2002 was two weeks ago. It is, objectively, a little pathetic to care this much about college basketball.

But it of course means so much more than just basketball. It’s an unbroken bond, an eternal tie to home, a direct line from the eight-year-old boy pounding his firsts on the floor in his parents’ room, to the high school kid screaming when Andy Kaufmann hit that shot against Iowa, to the nervous kid sitting at Mary Henson’s kitchen table, to the dumb college schmuck doing a shot at Murphy’s with Kiwane, to the broke wannabe writer saving up coins to be able to afford a pitcher of beer so he could watch Dee and Deron at the Irish pub down the street from his apartment, to the visiting lecturer happy to spend all day soiling the young minds of fresh-faced undergrads as long as there are Illini tickets at the end of it. And now not only do I get to still share it with my dad, I get to share it with my sons too.

Photo by Will Leitch.

This season’s version of the Illinois men’s basketball might be the best team they’ve had in 15 years. (You know, since Adam Miller was three years old.) They’re ranked No. 8 in the country and, three games in, they look better than that. (Though it got a little hairy on Friday.) I don’t plan on missing a game.

Still. It is a strange time for sports. As I wrote for New York last week, for all the solace during this terrible time that sports has provided, there is a downside to that, a considerable one. I’m still not entirely sure sports are morally justifiable right now. But when I watch this team, I’m beamed right back to that 13-year-old in the Dickey V T-shirt, where the woes and wonders of the last 30 years fade away, when I’m just screaming and jumping and grousing and clapping for the one thing I care about just as much right now as I did when I was the age my sons are now. I do not know if this college basketball season will finish, and while that’s concerning, honestly, I do not know how much of anything in the world right now is going to play out. All I can do is take care of what is front of me, what is happening right now, and try to make the most out of it and hope for the best down the line. Watching Illinois basketball provides me true joy, and a connection to the person I once was and will, in a way, always be. I feel happy when I watch Illini games. But mostly: I just feel grateful. I feel grateful to have anything in my life that has meant that much to me for that long. It’s rare to hold onto anything your whole life. I’m certainly not going to let go now. So: Go Illini.

Photo provided by Will Leitch.