This article is authored with input from Setu Chakrabarty, Purba Chatterjee, Sambarta Chatterjee, Utathya Chattopadhyaya, Susan Koshy and others.

On March 9, several students and faculty at the University of Illinois came together for a teach-in on “Dissent, Democracy, and the Crisis of the Indian University.” In the week leading up to the event, the group “Students and Faculty of U of I stand with JNU” had set up a booth on the main quad providing information to passersby on what they saw as the stifling of dissent in Indian universities. Those unfamiliar with the Indian government’s higher education policies would not be wrong to wonder what such a crisis is all about, and what, if anything, does it have to do with students here at the University of Illinois.

This crisis in Indian higher education has been in the pipeline for years but has reached a gradual tipping point ever since the current national government was formed in 2014 by the conservative Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). On one hand, the Prime Minister and key members of his cabinet have consistently ridiculed universities as spaces which produce ‘anti-national’ elements in the same breath as they have espoused their version of cultural nationalism by arguing that ancient India had plastic surgery and genetic science, all on the basis of literary epics. On the other hand, since November last year, research scholars across the country have faced cuts in an already paltry public fellowship scheme alongside a slew of other initiatives aimed at making scientific research profit-oriented and raising tuition for public education. Their protests against such neoliberalism has only been met with more suspicion, ridicule and slander by the national government. If that wasn’t enough, the government also continues to make appointments to leadership positions in public universities based on the loyalty shown to the current ruling party. Last year, the chairman’s position at the country’s most prominent film school was unilaterally handed over to a yes-man of the ruling party whose only credential in the rich and multilingual world of Indian film was a Hindi television serial based on a Hindu epic. The contenders for the post included multiple award-winning luminaries of Indian cinema in various languages. Amid this looming sense of a crisis, the formal opposition within parliament to such policies has found itself to be either miniscule or simply exhausted. Outside parliament, however, activist students have come to form a dispersed but resolute students’ opposition in India, united across cities and towns, and composed of students coming from diverse economic and social backgrounds, a large majority of whom have entered institutions of higher education after years of struggle to make the Indian government enact and implement affirmative action policies in higher education.

In February this year, the current momentum of this student opposition was catalyzed by events at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), an internationally well-known institution of higher education in New Delhi. Government-friendly television media ran sensationalist and Islamophobic reports of “anti-India sloganeering” and “terrorist sympathies” during a cultural event against capital punishment and possible miscarriages of justice in such cases. This led to the arrest of JNU Student Union President, Kanhaiya Kumar, and two others on charges of sedition and criminal conspiracy, despite their claim that they never raised any such slogans. Video evidence which purported to show Kumar making statements against India were later shown to be doctored. When Kumar was presented for trial, he was beaten inside the courthouse and concerned citizens who came to the trial were verbally and physically abused in broad daylight by an angry mob of lawyers sympathetic to the BJP. The same men also attacked the reporters covering the event. The apex court of India appointed a panel of lawyers to investigate such violence inside a lower court. They described the atmosphere as “surcharging, threatening and frightening.” The charges made by the police didn’t stand in court and all three students were released on bail, pending any further hearings. However, that didn’t stop the university administration from handing out extremely severe financial and disciplinary penalties after it conducted a “high-level enquiry” in which students weren’t even allowed a chance to depose and the faculty union unequivocally boycotted citing the unconstitutionality of the enquiry process. Students in the university are now on an indefinite hunger strike to force the administration to retract its punishments.

Frenetically covered by the pro-government television media across February and March, the resulting circulation of doctored videos fostered the impression that JNU is a hotbed of “anti-national” and “seditious” activity. An entire student body was condemned, without trial, by the media. Students faced death threats from fringe right wing nationalist groups. The university community responded to the situation by conducting regular teach-ins on nationalism and the meanings of freedom which were then telecast on Youtube.

Nothing new

However, such intrusion of Hindu nationalist politics into the functioning of universities and the BJP’s attempts to brand dissent as anti-national is not new. Weeks before the JNU controversy blew up, Rohit Vemula, a Dalit student at the Hyderabad Central University committed suicide following weeks of institutional harassment. Vemula, one of the many students from lower caste backgrounds who have entered public higher education on the basis of progressive affirmative action, was suspended from Hyderabad Central University following complaints by a student member of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the militant student outfit allied to the BJP, which was also responsible for provoking students in JNU. The complaint was even supported by the local BJP leadership, and even the national Minister for Higher Education wrote to HCU to ensure that action had been taken against Vemula and others. Vemula committed suicide after repeated attempts to appeal his suspension failed. Lower caste political movements, inspired by B.R. Ambedkar’s legacy, are largely opposed to the upper-caste Hindu ideology of the BJP and students who identify with such movements are increasingly becoming targets for the ruling dispensation in their bid to control dissent on university campuses. But Vemula’s poignant suicide note has since become a rallying cry for the growing students’ movement demanding justice for his death.

The story of Vemula and his fellow student activists highlights the deep seated discrimination that persists in Indian education. The caste system in Indian society places great emphasis on textual and scriptural knowledge, something that only upper castes can have access to. Over centuries, upper castes have come to be the primary interlocutors of knowledge, something which got further codified institutionally under colonial rule. That privilege has been reconfigured over the years but the predominant majority in higher education continues to be upper caste students, an imbalance which has only provisionally been corrected by affirmative action policies that enable Dalit and Other Backward Class students to enter public education.

Sedition and Policing

Against such a student opposition, the Indian government has taken recourse to British colonial laws. Using the rhetoric of ‘anti-nationalism’, the government and police have used Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalizes different acts as sedition. M.K. Gandhi, who was once arrested under the same law by the British said “affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by the law. If one has no affection for a person, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote or incite to violence.” The Supreme Court of India, in interpreting this law, has similarly stated that “strong words used to express disapprobation of the measures of government with a view to their improvement or alteration by lawful means would not come within the section. Similarly, comments, however strongly worded, expressing disapprobation of actions of the government, without exciting those feelings, which generate the inclination to cause public disorder by acts of violence, would not be penal.”

No acts of violence ensued after the February 9 protest at JNU. No evidence exists that any of the defendants intended any form of violence, or desired to incite violence from others. The suppression of free speech in JNU is thus not only based on a highly questionable law, it violates the constitutionally binding interpretation of that law by the Indian Supreme Court.

While sedition was the most prominent charge made by the government in the JNU case, the strategy in HCU wasn’t remarkably different. The HCU Vice-Chancellor, Podile Appa Rao has been given a free hand by the national government to use state police forces on the university campus. Following Vemula’s suicide, Appa Rao had quietly gone on leave to evade the media attention. He was one of the people charged for the responsibility of Vemula’s death, and has a pending police inquiry under the SC/ST Atrocities Act. Yet, despite being warned against returning to the campus, he did so. Students who were peacefully protesting his return were then brutally beaten and arrested by the Rapid Action Force and local police, had charges of violent activity filed against them, and those who weren’t arrested faced a besieged campus where food and water supplies were cut off and the local bank was forced by the police to suspend all debit cards issued to students. Meanwhile, faculty who supported the students were also arrested and following weeks of administrative apathy, faculty members from lower caste backgrounds resigned from all administrative duties in the university. Out on bail since then, the students have resolved to continue their struggle for justice in Rohith Vemula’s case as well as more equitable public education.

Responses

Universities are meant to be safe spaces for dissent and debate. Students at the University of Illinois have learnt the lesson the hard way, after a prolonged battle for the reinstatement for Steven Salaita ended in a court settlement last year. In a multicultural democracy like India, the voices of students from diverse socio-economic and religious backgrounds should be celebrated, not smothered. The greatest harm to democracy comes from actions that force students into the straitjacket of state-sponsored ideas.

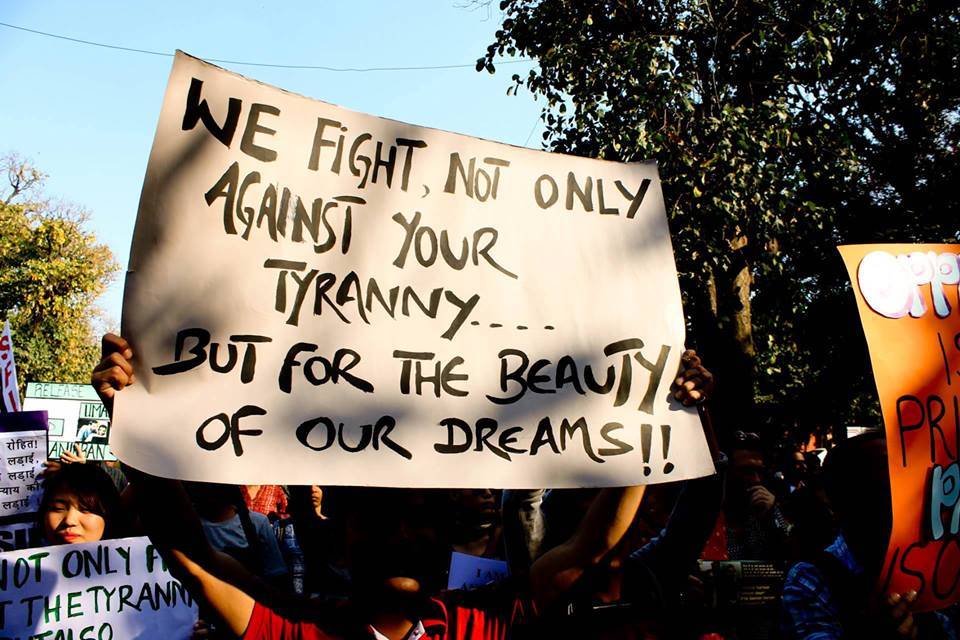

Provoked by this emerging student opposition in India, the #standwithJNU and #standwithHCU trended on Twitter as students from universities in four continents tweeted their support, read excerpts of speeches by Kumar, and signed petitions against the high-handedness of university administrations. Orhan Pamuk, Gayatri Spivak, Judith Butler, Noam Chomsky and many others wrote to the students as well as the JNU Vice Chancellor. The spurious manipulation of patriotic sentiments to suppress academic freedom has since drawn international condemnation from the press, as evidenced by editorials in the New York Times, Le Monde and the Guardian. But most importantly, the idea of a student opposition is taking root unlike ever before, where students are uniting across times and places to directly and coherently confront a national government every step of the way and completely on their own terms, by consistently using independent media and social media, even as they continue to foreground and participate in other movements for social justice inside and outside the university campus. Here at the U of I, students and faculty came together in support of such an opposition that celebrates the right to dissent and allows us to think of the student and the research scholar in more political ways than we have so far.