When I was sixteen, I asked my mother to buy me the stuff I needed to make a video game. At that time, I was obsessively replaying Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars and, especially, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (I’m told by semi-reputable sources that Majora’s Mask is worth another look — I gave up after getting sick to death of time resetting). She bought me How to Program in C++ on CD-ROM. It came in a green box that I never opened.

I fell away from gaming for a variety of reasons, but a big one was that I went to college. In college, gaming was a distraction, something you did when you could squeeze time in between driving your dinosaur to class and back to your cave to write really crappy papers about Paradise Lost on the world’s heaviest laptop.

But for Dr. Megan Condis, Morton native and Illinois alumna, video games are a subject of personal leisure and academic study. Condis recently completed her dissertation on video game culture, and to accompany it, she built a role-playing game.

But for Dr. Megan Condis, Morton native and Illinois alumna, video games are a subject of personal leisure and academic study. Condis recently completed her dissertation on video game culture, and to accompany it, she built a role-playing game.

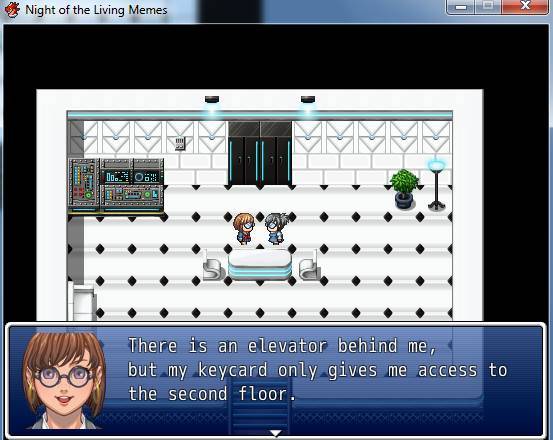

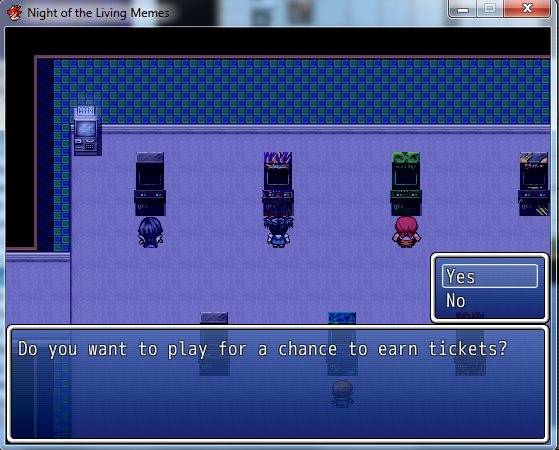

Night of the Living Memes was made with RPGMaker, and is available for play on any Windows system, completely free of charge.

I spent some time with Dr. Condis discussing her interest in video games, her first video game, and how she understands and hopes to contribute to gaming culture.

Smile Politely: Why video games?

Megan Condis: I grew up playing video games. My dad was a manager of a pizza joint that had arcade machines, and I remember pushing buttons on machines that had no money in them. Doing that was right up there with the movies for me.

When I went to college, I found out you could look at video games, you could study them, in the same way as literature or film. For a long time, I didn’t think doing such a thing was allowed. And there’s still a lot of controversy around studying video games in higher education. Some people in the community think they’re validated now, and others don’t want them to be because they don’t want them exposed to public view.

SP: What’s your favorite video game?

Condis: Chrono Trigger for Super Nintendo. It was the first game where a character could really die for real. It wasn’t like, “oh, Mario fell in a hole,” but something bad happened to someone I care about.

Chrono Trigger. Image courtesy of thatvideogamebog.com.

SP: Have you noticed an increase in people studying video games?

Condis: Yeah, part of it is that casual games got more popular on phones and on Facebook. It occurs to people to look at them. Academics who were kids during the ’80s and ’90s and played video games and are now like, of course this is a thing to look at. But there’s also an increase in established cultural criticism. Editors of academic presses say “I played words with friends on my phone” and become gatekeepers of what work gets published and what doesn’t.

SP: Do people who study video games consider themselves gamers? Why or why not?

Condis: I do, because I do play competitively. I’m not good or a professional, but the games that you see people professionalizing in like League of Legends and StarCraft II, I do play those games against other teams. It’s my sport, does that make sense? I’ll go home and be like, 8-10pm is scheduled to be my games.

League of Legends. Image courtesy of en.wikipedia.org.

But a lot of people who study are hesitant to identify themselves as gamers because gaming is associated with certain demographics of people, generally young, straight, white men who can afford an Xbox or good computer. It’s become this political action group rather than a subculture, it’s a group that feels as though it has been maligned in the popular media. Thus, if you criticize any individual game, it’s like saying gamers are racist, sexist, ignorant. So saying “I’m a gamer” can be a political statement that can, for some, translate to saying (or being heard as saying) “I’m against cultural criticism of games, I’m against social justice warriors invading our space.” And some people are afraid of being misheard.

But I continue to call myself a gamer because it is nerdy. If you grew up five years after me, it would be cool, but for me, it was nerdy — and that’s why I want to hold on to it. Nerds won, we own pop culture.

As an academic, I’m also interested in the boundaries of identity but also the sense of privilege that comes from needing to pick a team, especially with the rise of new technology.

Back in the day, you had to have a Nintendo or Sega to call yourself a gamer. Almost everyone now plays some game but there is this group that is very interested in maintaining that identity, which is weird. There’s no identity of “TV watchers”; there are fans of distinct shows. But right now, gamers like those involved in #gamergate want to have that distinction, like “we don’t want those other people to be recognized as gamers because they can’t give each other the secret handshake any longer.”

SP: Are there any games that haven’t been popularized?

Condis: Yes, visual novels or dating sims, are still stigmatized. Visual novels are generally romance-based, where your character seeks relationships with other characters, and that’s what the plot is, that’s the whole point. There’s an anxious defensiveness within the genre because, on the one hand, there’s all this romance stuff where characters are supposed to be sweet to each other, to form bonds with each other. But then, if you do this, you get rewarded with pornographic images. So if your character gets a second date with another character because you brought her flowers, the game rewards you with a picture of boobs or something similar.

Visual novel. Image courtesy of gmc.yoyogames.com

You also can’t really spectate a visual novel, because it’s meant to be personal. There’s a big trend in streaming your gaming experience to hundreds or thousands of people at conventions or online. But if you stream a choose-your-own-adventure, which is essentially what a visual novel is, it’s a very personal plot. And while some people would comment on the action by making fun of it, others are deeply moved.

Finally, visual novels are not very popular as a genre because they allow for immersion and experimentation. Just like fanfic is a feminized version of an already-feminized form (the novel), where women write themselves into stories, visual novels allow people who are interested in becoming other characters to write themselves into those stories. In a story about an abusive husband, for instance, a woman might occupy the role of the husband, to see what it’s like to be that type of man. And she might choose to be nicer to women within the game, but still as the man. Or she might choose to not be nicer. And that type of experimentation can make a lot of people uncomfortable.

SP: Tell us about the game you made.

Condis: It’s called Night of the Living Memes. It’s about the way that, because it exists online, Internet memes and memetic information can get spread through that community and adopted as gospel so fast.

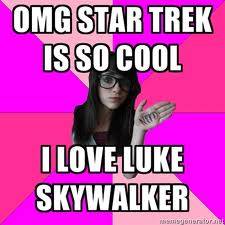

There’s this group of memes about who counts as a real gamer and how that’s gendered. There’s the fake geek girl meme where a girl pretends she likes games because she wants attention or wants to trick guys into giving her money for her stream on Twitch. This meme spread really fast, but if you’re outside of it, it makes no sense because it’s just a girl with the word “nerd” on her hand. Inside the community, though, she doth protest too much. In the text she’s always saying something about how she loves games so much, but she always makes a mistake like “I love Zelda so much when he swings his sword around.”

They proliferate and it becomes a substitute for actual experience, it becomes a trope online but in real life it makes you think “all women are fakers because obviously I’ve met them online.”

Fake nerd girl. Image courtesy of nerdybutflirty.com

In the game, people exposed to memes become zombies who spout the same claptrap the whole time. Your party is of three women who go to a gaming convention, and have to decide what to do. You have to replace that meme with other content and make your own objects and popularize them — things you take around and expose people to, and some of them take it up and internalize what you’ve made. When they take up the new meme, everyone becomes more productive and egalitarian.

Night of the Living Memes. Image courtesy of Megan Condis.

There’s no escaping memes, but there are ways to use them productively. You can’t get people to unthink or unsee something in real life or in this game. But you can take a little shard of the Internet (which doesn’t decide what gets popular and what doesn’t — people do that) and give each person a little shard to transform them. They’re able to see this other facet and that changes how they think; they don’t change back, they change again, if that makes sense.

There aren’t bad and good memes. We need to make sure that there are different kinds of voices out there for people to encounter before they start to think “well, that’s all there is.” You need to go to different corners of the Internet and see all different kinds of voices, and that’s how we become complex people and how we become complex characters.

SP: How did you make your game?

Condis: RPGMaker, because aesthetically the pixel sprites are reminiscent of that era of gaming I love (not 3D rendered realistic things). And also there are assets that are there. The game is like, “here are fifty dudes that are premade,” so you can use premade assets if you just want to tell a simple story.

For me, I can learn how to do the programming stuff. But I didn’t feel capable of doing programming and learning how to make things that are made out of pixels and animating those things. I just wanted to buy a thing that has that already. And there’s a huge community around this engine — it’s been around forever. So people have just built other random assets. The engine I’m using now is new and intuitive, but no community and no tutorials. But for RPGMaker, you can ask questions like “How do I animate lightning bugs?” and someone has written a script and you can just pop it in your game, or someone who wrote one will teach you about their script so you can do it yourself.

There’s an image of game designers that’s like the old timey writer, who’s alone and it’s late at night and he’s smoking a pipe, but it’s really not like that. You can choose an engine that makes it more like that, and that sounds really hard. But you can also go out and say that I’m relying on these community assets but I’m using them to tell my specific story.

These scaffolding systems though have a lot of assumptions too — the characters are all white, and one sprite that looks Middle Eastern or is maybe just a tan white guy. Why is the assumption that people want to tell stories about King Arthur and not about the Monkey King or other mythology? Not explicitly, but this suggests that the first game you make is Tolkien-esque with white people. Those things have a subtle effect. It’s not malicious but I’m sure they just market-tested it and a lot of people probably played D&D and they wanted to make a white elf character.

SP: How many people have played your game?

Condis: It’s been downloaded 30 or 40 times. But my hope is that those people give the zip file to other people; anyone can download and play in Windows. I’m looking into getting it on other distribution platforms. The underlying structure was designed for PCs but I want to make it available on iOS and Android, so that it’s not aimed at hard core, elite PC gamers. The more platforms, the more potential players. Just download, click open and play — but some are scared because it might look like a virus. No one on my committee has played it. They read the development blog but were like “No, I didn’t run around and fight trolls, I don’t have time for that.”

SP: Any advice for DIY game developers?

Condis: Don’t have a vision in your first two or three games; just make a thing and then you can figure out how to turn it into something that fits your vision later. If you start with really complex things like exchanging trinkets for weapons, you might get overwhelmed and quit. But if you start with just walking a dog around some obstacles, that’s a game. And now you know a lot more for your second one.