Read Part One of this series here, and Part Two here.

Read Part One of this series here, and Part Two here.

We’ve rambled on about the emergence via modern science of chemical warfare, inorganic nitrogen fertilizers and high explosives, the contest over Afghanistan 100 years ago, world natural gas reserves and usage, and today’s gas pipeline politics, maneuverings and wars in central Asia.

So let’s turn to the local organic food movement — the C-U farmers markets, Common Ground Coop, the UI student organic farms, chefs sourcing product locally, and all the other local manifestation of the growing national movement to produce more healthy foods from local soils.

It’s important to see this as not some liberal agrarian romanticism soaked in nostalgia for the hearty yeoman land steward (although sometimes it is portrayed that way). Nor should we see is it as some alternative universe divorced from existing political economy, geopolitics and wars, which are always about resources.

The connection of local organic farmers to American troops in Afghanistan is not as attenuated as it might seem.

The thread so far has focused on natural gas, but other agricultural inputs could have served: water or soil, or phosphorus or any number of other resources. But right now, gas is the resource most in play in global politics.

The related thread has been soil fertility. Its decline in the nineteenth century created a looming severe problem, which is why Fritz Haber and others were trying to synthesize ammonia. Declining soil fertility, which has led to the decline of civilizations, driven war, and been the cause of famines, may be our biggest challenge. It’s the heart of the local organic movement: building soil to create a regenerative rather than an extractive agriculture. Easier said than done.

In August, Governor Quinn signed a law by which state agencies must purchase 20 percent of their food from local sources by 2020. A good idea, but the local food supply chain is miniscule and fledgling. One local organic farmer said he could turn his whole substantial operation over to producing nothing but cherry tomatoes and still wouldn’t come close to meeting the U of I’s demand for them. Unless the U of I makes all three squares a day just shelled corn and soybeans, this 20 percent just ain’t gonna happen in 10 years, despite best intentions.

In August, Governor Quinn signed a law by which state agencies must purchase 20 percent of their food from local sources by 2020. A good idea, but the local food supply chain is miniscule and fledgling. One local organic farmer said he could turn his whole substantial operation over to producing nothing but cherry tomatoes and still wouldn’t come close to meeting the U of I’s demand for them. Unless the U of I makes all three squares a day just shelled corn and soybeans, this 20 percent just ain’t gonna happen in 10 years, despite best intentions.

As a young political economist once wrote, “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please.” You have to deal with the hand that’s “given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

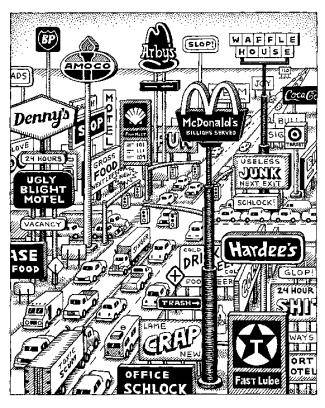

In this case, the dead generations put us between a rock and a hard place; we have a huge mismatch between population and real soil fertility. We are hooked, and have to get unhooked, but how? The material and cultural accretions of the longue durée of history make it damned hard to change direction. We’re more invested in the old world built on cheap but finite fossil fuels than we imagine. We are barely aware of the material and cultural parameters history has set. We consider them natural or normal.

The wag defines modern farming as the use of soil to convert oil and gas into food. That’s not the whole of it, but still, a third of the earth’s population would starve to death were it not for inorganic fertilizer. Agriculture now uses more energy than it produces.

The wag defines modern farming as the use of soil to convert oil and gas into food. That’s not the whole of it, but still, a third of the earth’s population would starve to death were it not for inorganic fertilizer. Agriculture now uses more energy than it produces.

Fortunately, natural gas is currently cheap, clean and plentiful, as the gas industry tells you in their ads. That doesn’t mean it’s free, limitless and pollution-free, but because of its characteristics, gas has increasingly replaced other fuels in home heating, industry, and electricity generation, boosting demand.

Transportation will be next to put its thumb on the demand side of the scale. Two weeks ago Qatar Airlines announced the world’s first use of natural gas-derived fuel on a commercial flight from London to Doha. Jet fuel is a significant part of overall petroleum consumption, and switching aviation to natural gas would greatly increase natural gas consumption, but it pales in comparison to what gas substitution in automobiles and trucks would do. Part of the T. Boone Pickens plan is to do just this.

Transportation will be next to put its thumb on the demand side of the scale. Two weeks ago Qatar Airlines announced the world’s first use of natural gas-derived fuel on a commercial flight from London to Doha. Jet fuel is a significant part of overall petroleum consumption, and switching aviation to natural gas would greatly increase natural gas consumption, but it pales in comparison to what gas substitution in automobiles and trucks would do. Part of the T. Boone Pickens plan is to do just this.

There are all kinds of energy substitution schemes around, but a lot of them are looking at natural gas as the replacement, as well as the way to help stem global warming by displacing coal and gasoline. But substitutions often have unintended consequences. For instance, the corn ethanol boom has driven up world food prices, leading to many hardships. This at a time when one in seven is hungry and experts think food production will have to grow by 50% in the next 20 years to meet demand.

Gas consumption is going to rise, probably sharply. Production and reserves will rise as more is discovered and technological gains and rising prices make more extraction possible. Rising prices will make food more expensive because five percent of the world’s gas is used to make fertilizer.

We want to go quick, with quick returns, but soil-building takes time — years, and it’s easily washed away. We inherited a bountiful prairie, but half of it is now at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, where the applied nitrogen is killing off sea life.

But nitrogen fertilizer is not just killing the Gulf. It contributes to global warming and it kills the soil. I recently toured via hayrack ride one of our local organic farms, and as we cruised by the neighbors’ conventional corn field, our guide pointed out that nothing was growing in the field except the corn. What once was phenomenally productive on its own, with proper rotation and care, is now dead soil, a place to stick corn plants and dose them.

So what is to be done hereabouts? Obviously supporting and working to expand existing local food businesses and institutions matters, but it’s not enough. In his keynote address last week at the World Food Prize meeting in Des Moines, at which he announced a $120 million gift from his foundation to boost agricultural production, marketing and farming expertise in the developing world, Bill Gates said this: “The next Green Revolution has to be greener than the first. It must be guided by small-holder farmers, adapted to local circumstances, and sustainable for the economy and the environment.” This is good to hear about plans for the developing world, but the same concept needs to be applied here.

So what is to be done hereabouts? Obviously supporting and working to expand existing local food businesses and institutions matters, but it’s not enough. In his keynote address last week at the World Food Prize meeting in Des Moines, at which he announced a $120 million gift from his foundation to boost agricultural production, marketing and farming expertise in the developing world, Bill Gates said this: “The next Green Revolution has to be greener than the first. It must be guided by small-holder farmers, adapted to local circumstances, and sustainable for the economy and the environment.” This is good to hear about plans for the developing world, but the same concept needs to be applied here.

Tax laws, subsides past, present and future; archaic property laws, research funding systems, government regulations and all our cultural predispositions and attitudes make it exceedingly difficult to farm in a regenerative manner. Only the most ideologically committed, who are willing to sacrifice a lot to make a go of it, can do it. That keeps it miniscule and fledgling. That has to change. But even if a comparative advantage on a level playing field were to be achieved for local organics, and there is evidence that this is or will be increasingly the case, there are still powerful interests opposed to it.

With the public sector, government and universities increasingly captured by powerful economic/political interests, room to maneuver is scarce. It’s easier to fight wars for gas than to turn the ship of domestic food production around. A project to make local agriculture regenerative has to take on the kind of decisions powerful interests are making. Regenerative agriculture has long been the poor stepchild at land grant universities in terms of funding and prestige. Constituencies are needed to demand more research here, and in the field; why not pay local organic farmers to do studies, and provide them with the necessary resources? Why not work on ways to get more land in regenerative production, instead of basically supporting the old ways?

Government planners and taxing bodies, often in cahoots with developers, continue to think of agriculture as the lowest, worst use of land. We need to start thinking of it as the highest, best use and a development tool for the future. Plans that create more sprawl-inducing roads on the urban periphery and that destroy agricultural land need to be challenged.

The obscenity of making motor fuel from food crops in world where people starve needs addressing. The whole point of ethanol is trying to keep a dying old world going, and making big winners out of firms like ADM, Monsanto and Cargill. It is not sustainable, despite the corporate propaganda you might have seen on “Public” Television.

It takes effort — thought, discussion and political and physical action — to change things, to go against the usual drift. It means taking on the presumptions that rule us, articulating why change is needed, and what kind of change is possible and how to do it. The heroic efforts of organic and small scale farming pioneers are just the start. As North Carolina farmer and “Grist” columnist Tom Philpott says,

“The sustainable-food movement needs to step up and start grappling with big questions. [There are] three big challenges for the sustainable-food movement as it scales up: 1) soil fertility-in the absence of synthesized nitrogen and mined phosphorous and potassium, how are we to build soil fertility on a larger scale?; 2) labor-sustainable farming requires more hands on the ground; who’s going to work our farm fields, and at what wages?; and 3) access-in an economy built on long-term wage stagnation, how can we make sustainably grown food accessible to everyone?”

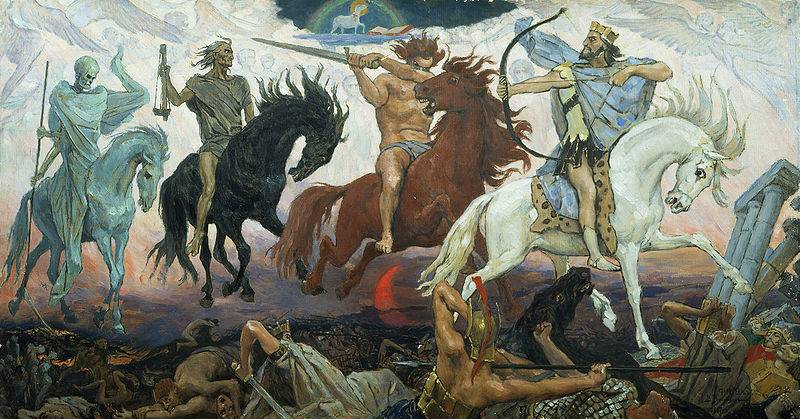

The alternative is literally the four horsemen.