“Dangerous” ideas have always existed and been debated on university campuses. It is perhaps the sign of a healthy university system and society that this happens; academics are meant to think about the historic, current, and potential future problems facing humanity. In his latest book, University of Illinois Emeritus Professor of Journalism Matthew C. Ehrlich looks at two cases of academic freedom on the U of I campus in the 1960s. Dangerous Ideas on Campus: Sex, Conspiracy, and Academic Freedom in the Age of JFK considers the cases of professors Leo Koch and Revilo Oliver. In 1960, Koch was fired for writing a letter to the Daily Illini defending premarital sex. Four years later, Oliver claimed a communist conspiracy was the source of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and made a slew of white supremacist comments. Oliver was not fired.

Dangerous Ideas on Campus considers who should be in charge of determining which academic ideas are valuable, viable, and worthy of pursuit, as well as the role of institutions, like the University of Illinois, in trying to establish morality and acceptable ideas on campus. It considers the specific social and cultural mechanisms and ideas circulating in postwar America that facilitated the responses to these two cases of academic freedom. The book implicitly asks: What does academic freedom actually afford scholars and students? How do those contested ideas reflect and inform American culture?

Reading this book, it is clear that in many ways, not much has changed since the 1960s. The most recent iteration of the culture wars has continued the discussion of what young adults should/could/must be intellectually exposed to, and who should do the exposing, so to speak. While in the 1960s the stakeholders — administration, donors, Boards of Trustees, politically connected alumni — seemed to be a relatively small, albeit powerful group, the corporatization of higher education expands those with great influence to include those with a (social media) platform, as well as parents and students as “customers.” But the book makes clear that a whole lot has indeed changed since the mid-20th century, including what is or isn’t considered a dangerous idea.

Even if you’re not particularly interested in the historic politics and interests of higher education or the U of I, there is a fundamentally human story presented in Dangerous Ideas. It’s the story of toxic coworkers, pettiness, and delusions of grandeur. No matter the time or place, people will find ways to betray each other to further their own ideological and material interests. Plus, beloved Urbana native Roger Ebert makes a bit of a cameo in this book.

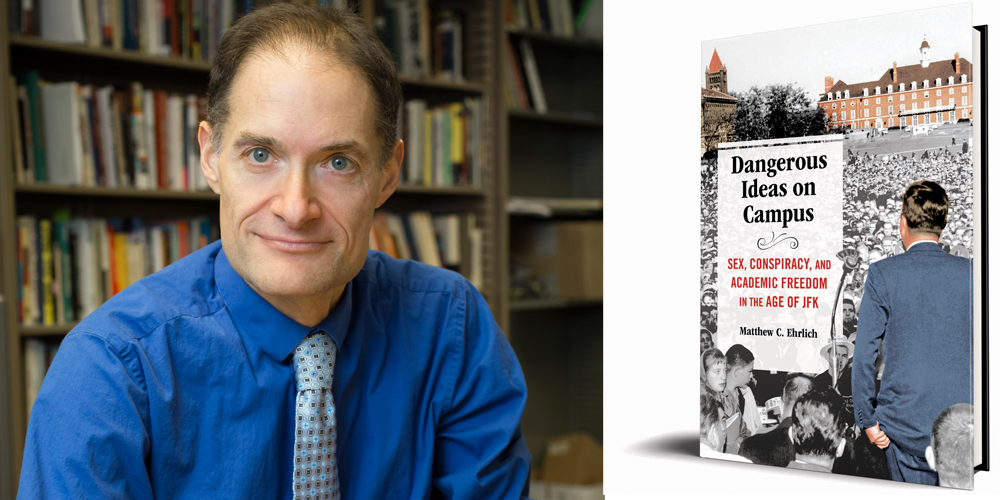

I found this book to be incredibly interesting, relevant, and insightful, and I learned a lot about the history of the U of I. I recently spoke with author Matthew C. Ehrlich about his book; our interview is below. In the meantime, you can order your copy of Dangerous Ideas on Campus: Sex, Conspiracy, and Academic Freedom in the Age of JFK from the University of Illinios Press.

Smile Politely: One aspect of your book I couldn’t stop thinking about was the researching of the institution, the University of Illinois, where you taught for many years. No research or investigation is wholly without bias, of course, and I am curious about your approach to that component of your project. Could you talk a little about that? How does the temporal distance from the mid-20th century create an intellectual or academic distance for you?

Matthew C. Ehrlich: I do have strong ties to the university. I was a full time professor there for more than 20 years (and still teach there occasionally); before that, I worked at WILL radio while getting a Ph.D. from the U of I. In addition, my father and my aunt earned five U of I degrees between them. That said, I didn’t feel at all awkward or constrained in writing about the university. With Dangerous Ideas on Campus, it certainly didn’t hurt that the events in question had occurred six decades previously and that almost all the principal characters had since died (it can be touchier addressing recent happenings or living people). But I view the U of I much like any other large university with a long history, not as uniquely beneficent or venal. It’s experienced both highlights and lowlights, proud moments alongside not-so-proud ones. When we study specific episodes from the U of I’s past, we can find parallels with what many other universities were dealing with during the same time periods. That’s what drew me to examining the Leo Koch and Revilo Oliver academic freedom cases — they centered on issues important not just to the University of Illinois, but also to higher education broadly, both past and present. And whatever is important to higher education is also important to our society and culture at large.

SP: Following up on that idea, I see this sort of research as an opportunity to engage on a small scale with difficult histories of misogyny and racism, in particular. I believe there has to be a way to acknowledge the realities, harms, and legacies of the past while finding ways to build toward a more inclusive and equitable present and future (though I acknowledge that we do not all agree with what the present or future should look like, or even the facts of the past). What are your thoughts on that sort of excavation, and the usefulness for the contemporary/future?

Ehrlich: Academic freedom controversies like the ones involving Koch and Oliver are good entry points for examining just those sorts of histories. The controversies always are triggered by debates over what should be taught and not taught, what should be researched and not researched, and what should be said and not said. Leo Koch was fired after writing that sex between unmarried students was acceptable. He implicitly argued that society needed to question traditional gender roles, particularly the double standard holding that what was acceptable for young men wasn’t acceptable for young women. That argument raised a furor in 1960, even though it seems tame today. Revilo Oliver got into trouble for writing that the recently assassinated John F. Kennedy had been a loathsome traitor liquidated by an international communist conspiracy. Again, that argument raised a furor in 1964; today, people are more apt to view Kennedy critically and to think that some sort of conspiracy was behind his murder. But Oliver also stirred controversy by being virulently racist and anti-Semitic in his public speech, viewpoints that seem even more abhorrent today. Unlike Koch, though, Oliver held tenure, and because there was no evidence that he was pushing his political views in the classes that he taught, he kept his job.

There are important lessons here. Public opinion never should be the standard to judge what ought to be taught, studied, or said on campus, in part because opinion can shift over time and accept more progressive ideas about inclusivity and equality. Allowing people outside the faculty ranks to restrict the exchange of ideas — even ideas that seem truly dangerous, such as Oliver’s — will in the long run inevitably squelch progressive thought more than it will reactionary thought, because (as history shows us) progressive thought is more likely to provoke backlash. And universities must be willing to embrace debate and controversy. Students need to grapple with the classically liberal idea that truth and merit will eventually triumph, even as students also need to grapple with ideas questioning the whole notion of meritocracy and challenging deep-seated misogyny, racism, and homophobia. The goal never is to “indoctrinate”; the goal is to encourage thoughtful examination of difficult issues that remain stubbornly persistent.

SP: What was most surprising to you during the course of this project?

Ehrlich: It probably should not have surprised me that Revilo Oliver and his wife Grace indirectly worked to get Leo Koch fired. They funneled information about purported subversives at the U of I to an archconservative minister who launched a letter-writing campaign calling for Koch’s dismissal. That happened at the same time that the Olivers were protesting that the university was out to “get” Revilo for his outspoken opinions. (People who complain the loudest about how they are being muzzled are often the quickest to try to muzzle other people.) I also found that people 60 years ago expressed the same worries and criticisms about college students that they still do today: the students were supposedly too fragile, frivolous, and coddled. That seems to be a perennial theme, whether the year has been 1962 or 2022.

SP: Do you think much has changed since the 1960s in regards to ideas of academic freedom?

Ehrlich: The Koch case encouraged some strengthening of academic freedom protections. The American Association of University Professors added language to its Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure indicating that “extramural utterances” (that is, a professor’s expression as a private citizen) “rarely bear upon the faculty member’s fitness for continuing service.” Other than that, the basic AAUP principles asserting faculty freedoms of teaching, research, and extramural speech have remained largely unchanged since the 1960s. However, in recent years universities have become increasingly reliant on adjunct or contingent faculty who don’t have the protection of tenure. Much of that trend stems from financial pressures on higher education (tenured faculty are more expensive), but there are also political pressures opposing tenure for faculty whose teaching, research, or expression is deemed controversial. That in turn represents one of the biggest threats to academic freedom these days.

SP: What do you think the media and we, as consumers of the media, can learn from the Koch and Oliver cases?

Ehrlich: The media are not and never have been monolithic. For example, there are obvious differences among Smile Politely, the News-Gazette, and the Daily Illini, just as there are clear differences separating WEFT, WCIA, and WPGU. In the cases of Koch and Oliver, many news organizations were sharply critical of the two professors’ speech (the mainstream Chicago newspapers were unanimous in calling for Koch’s firing). But the Daily Illini supported both professors even while its columnists decried Oliver’s rantings; the students understood the importance of protecting free expression even when they didn’t agree with it. Contemporary media producers and consumers should similarly appreciate the importance of free expression, and we should seek out multiple news outlets as opposed to relying on just one. We also should recognize that certain outlets (including on social media) may play up only the most provocative or inflammatory aspects of a particular controversy or take seemingly damning comments out of context. Again, faculty ultimately should judge the merits or demerits of academic freedom cases — not transient public opinion that some folks may try to rile up for the sake of money or clicks or votes.