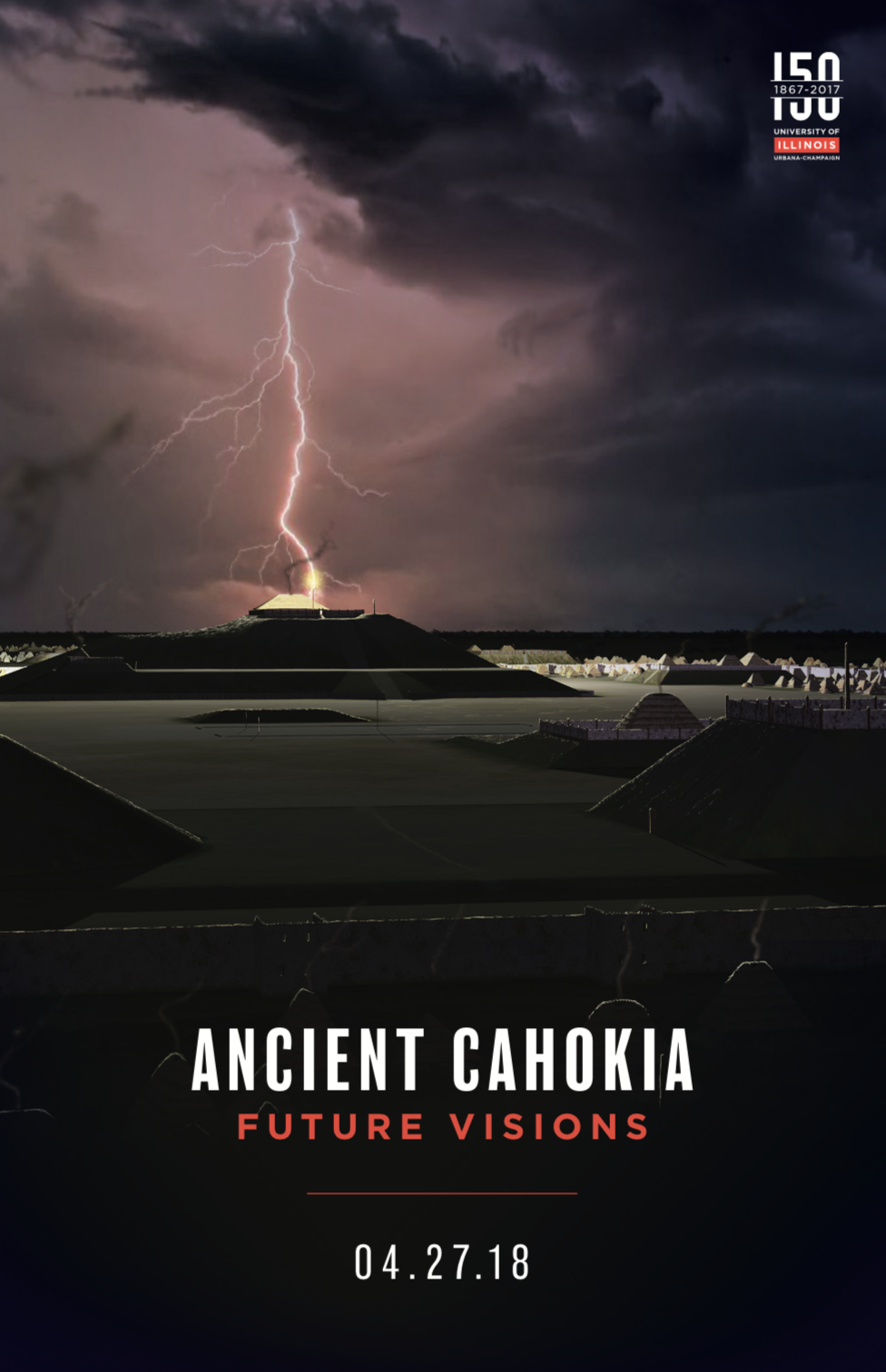

On Friday, April 27th, the University of Illinois hosts the Ancient Cahokia Future Visions Conference. According to the press release:

The Illinois State Archaeological Survey (ISAS)–Prairie Research Institute (PRI) is bringing together world renowned archaeologists and leaders from around the country to take part in a public conference that will rethink the global relevance of an ancient American Indian city—Cahokia in southwestern Illinois—for today’s world.

The Ancient Cahokia Future Visions Conference ( is part of a series of open forums at the University of Illinois intended both to celebrate the land grant institution’s sesquicentennial (150th) anniversary and to honor its esteemed tradition of research.

Illinois Governer Bruce Rauner will make opening remarks, Illinois Lieutenant Governor Evelyn Sanguinetti, and an array of esteemed Cahokia scholars and experts will be presenting at sessions throughout the day.

UIUC is both examining the ancient American Indian past and continues to grapple with the legacy of Chief Illiniwek, evidenced by UIUC Chancellor’s “Critical Conversations” about the Chief. I spoke with Ancient Cahokia Future Visions Conference presenter Marisa Cummings (Miakonda) to discuss her involvement in the conference, the legacy of Native American communities in Illinois, and her hopes for Ancient Cahokia Future Vision Conference participants.

Marisa Cummings (Miakonda) is originally from Sioux City, Iowa. She is a member of the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska and Iowa and belongs to the TeSinde or Buffalo Tail Clan of the Sky People. Cummings holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Iowa in American Studies and a Certificate in American Indian/Native Studies. She currently serves the University of South Dakota as the Project Coordinator for a grant through the Office of Violence Against Women. Prior to this, Cummings held the position as Chief Tribal Officer for the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska. She has also served her people in higher education as an administrator for Little Priest Tribal College and through the Center for Diversity & Enrichment at the University of Iowa.

Cummings has done extensive research in relation to the Omaha Tribe and the Missouri River. She organized and led actions against the Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) for their involvement in the Dakota Access Pipeline and was involved at Standing Rock during the pipeline resistance.

Angela Patton, Media Coordinator for Illinois State Archaeological Survey and the Prairie Research Institute explained that Cummings was invited because she has been an advocate for land preservation, most notably during the Dakota Pipeline protests, and for her advocacy of other issues related to Native American peoples. Patton stated, “We also thought she would add a very unique perspective when talking about Cahokia and other sacred land spaces.”

Smile Politely: Why did you agree to participate in the Ancient Cahokia Futures conference?

Marisa Cummings: I agreed to participate in the Cahokia Conference because I have established a relationship with Dr. Pauketat (the Associate Director for Research at the Illinos State Archaeological Survey) over the years and I believe in the work he is doing to preserve what is called Cahokia from future destruction.

SP: Can you describe your personal connection to the Cahokia area?

Cummings: I was raised by my father on the oral tradition of Cahokia. I know that our people visited and had a ceremonial connection to the city, although we resided to the north. Cahokia is used as an example of the complexity and intellectual capacity that people indigenous to the Americas possess. Our spiritual beliefs manifested in our environment and daily world view. That spiritual connection has never been lost.

SP: What do you plan to share with the UIUC community during your presentation at the conference?

SP: What do you plan to share with the UIUC community during your presentation at the conference?

Cummings: I hope to relay a message of continuance in regards to Native peoples connection to place and the spirit realms. Our voice is often silenced in academia and our spiritual worldview is often pushed aside as an unreliable source. In reality, our people had thousands of years of applied science, astronomy, agricultural practice, medicinal knowledge, and health practice. Through colonization, many academics view our culture and world view as lost. In reality, there is a continuance of knowledge that is connected to places like Cahokia.

SP: As the UIUC community has been grappling with the legacy of Chief Illiniwek and the use of a Native American faith leader as the school’s mascot, how would you advise our community to move forward on this issue?

Cummings: I have been keeping informed about the mascot issues in the community. Your community will not move forward until leadership confronts active racism and puts an end to the discussion. We know that the perpetuation of Native American mascots harms Native children’s self image and self esteem. We know that Native mascots operate on a stereotypical ideology. The Native community at U of I has openly spoke about their dislike of the mascot. If not for the practice of systemic and institutionalized racism, why is this topic still even on the table?

SP: In your opinion, how does Central Illinois more broadly navigate Native American removal from this area in the early 19th century and the subsequent establishment of the university by the mid-19th century?

Cummings: In my opinion, every state has a strong history of genocide towards Native people and a history of removal. The entire basis for statehood was prefaced on removal of Native people to make room for settlers. The word “removal” is synonymous with rape and murder. United States policies and institutions, such as institutions of education, have inflicted economic, physical, emotional, and psychological harm on generations of Native people. As an institution, the University of Illinois has an opportunity to help mend these wounds or continue to harm. It is a choice. It is a choice rooted in their power and privilege.

SP: Can you recall instances of disrespect against you personally as a Native American?

Cummings: As a young student at the University of Iowa, I recall activist Frank LaMere coming to campus. It was a weekend when the University of Iowa would play the University of Illinois in football. I remember the uproar when someone broke a pipe and left it in the Iowa Memorial Union in response to the protests that University of Iowa students were launching against the mascot coming to our campus. This incident illustrates the disrespect, disregard, and dehumanization of Native people and our spiritual practices by the supporters of the mascot. It caused emotional harm to the Native students on campus. It made me feel as if I did not belong at the institution. When we consider generations of systemic racism and genocide, why would anyone want this tradition of disrespect to continue if not to perpetuate racism towards Native people?

As a child, I was the only Native child in my class. My classmates would run around the room and make a sound over their mouth with their hand. “Marisa is an Indian!” and “WHOOWHOOWHOOWHOO!!!” I would sit at my desk humiliated, ashamed to be UmoNhoN, and hurt. I would cry. My teacher would watch and do nothing. Those incidents caused me harm and affected my self esteem and my productivity in school. Those experiences were perpetuated by the practice of stereotypical images of Natives in the media and as mascots.

SP: In your work as an educator, how do you raise the consciousness of non-Native people about the history, legacy and restoration of Native rights and resources to a new generation of Americans?

Cummings: My spiritual work is rooted in the healing and perpetuation of my UmoNhoN language, culture, traditions and spiritual way of life. This is very time consuming work. As a people we are responding to generations of trauma. We also must put our time and energy into continuing with ceremonies, learning and speaking our language at home, educating our children and young relatives in our way of life. This is my priority. If non-Native people ask me to speak, such as at this conference, and I can lend to their greater understanding as an ally to our people, that is good. But one must remember that my people exist as a Nation within an oppressive Nation. It is not my responsibility to educate settlers on their oppressive history and the benefits they receive at the expense of my peoples’ genocide and removal. They can go out and learn that on their own. I can only hope to build allies that may choose to gain understanding so that sacred sites are not destroyed and my peoples’ relationship with creation is not diluted any more than it already has been through the destruction of our earth mother and precious waterways.

SP: Finally, what do you hope participants gain from participating in the Ancient  Cahokia Futures Conference — particularly with regard to Native American communities?

Cahokia Futures Conference — particularly with regard to Native American communities?

Cummings: It is my hope that participants at the conference gain a stronger understanding of the spiritual and cultural significance of sacred places and waterways and then become allies in the protection of these amazing places.

Registration for the Ancient Cahokia Future Visions Conference is now closed. Be sure to follow the conference via social media at Prairie Research Institute via Twitter @PrairieResInst and Facebook, and on the event Facebook page.

To learn more about Ancient Cahokia, check out the Cahokia’s Religion: The Art of Red Goddesses, Black Drink, and the Underworld exhibit at the Spurlock Museum in collaboration with The Illinois State Archaeological Survey until May 20th.

Nicole Anderson Cobb, PhD, is a Staff Writer for Smile Politely.

Screenshots from Ancient Cahokia Future Visions Conference program. Photo of Cummings at Interpretive Center at Good Earth State Park, South Dakota courtesy of Marisa Cummings.