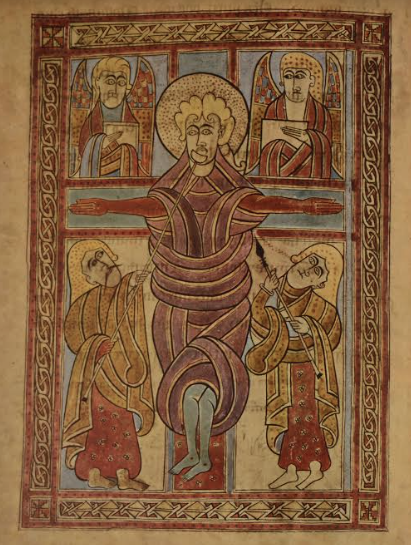

Everyone’s a little bit Irish, even the University of Illinois. Last week, the Spurlock Museum opened its exhibit “Medieval Irish Masterpieces in Modern Reproduction.” The exhibit, which will be open to the public until April next year, contains modern recreations of medieval Irish art, including metalwork and facsimiles, that have been housed in the University archives since 1916. Curated by Charles Wright, a professor of Old English literature at the University, the exhibit celebrates the history of the University of Illinois, the history of Ireland, and the art of reproduction.

Wright discovered the large collection of Irish medieval art reproductions housed at the University, and came up with the idea for the exhibit, last year while teaching a class on Old Irish literature. Soon after, Wright teamed up with Kim Sheahan, the Assistant Director of Education at the Spurlock Museum, to create a complete art exhibit. There was only one catch. Wright wanted the exhibit to be up and running by fall 2016.

According to Sheahan it takes an average of two years to prepare a temporary exhibit like the one curated by Wright, and the exhibits featured in Spurlock Museum are planned at least four years in advance. So why would Sheahan agree to help organize and create an exhibit on such a short timeline? Well, the year 2016 is significant in Irish history as well as the University of Illinois.

The year 2016 marks the the centennial anniversary of the Irish Easter Rising as well as the centennial of Professor Gertrude Schoepperle’s efforts to create an Irish Foundation at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. A large portion of those efforts included persuading the University to purchase the artifacts on display in the exhibit.

Despite the fact that the originals of these masterpieces are actually housed at the National Museum of Ireland, “the reproductions have significance and value in and of themselves,” Wright says. For one, the Irish reproductions are historically important due to their role in Gaelic Revival, a nationalist movement that began as Ireland was beginning to seek independence from Great Britain. Gaelic Revival was a way to revitalize the Gaelic language, culture, and art for the Irish people. And at a time when Irish people felt like their culture was dying out, reproductions of medieval metalwork and scripts helped make Irish culture widely available.

In addition to helping perpetuate Irish history and culture, reproductions have a history all their own. Edmond Johnson, an accomplished Irish jeweler, created 184 pieces of Irish reproductions for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign doesn’t own those particular pieces, but Johnson’s company created many of the reproductions that can be viewed at the exhibit. Each reproduction has its own story to tell, from who bought it and why, and the story of why the original was created in the first place. Reproductions contribute to the complexity of history, while reminding us of an event, time or place.

Reproductions also do this, while reminding us of our own failings in the way of art. For example, despite Johnson’s expertise and prowess in the creation of reproductions, there were styles and motifs he admitted to being unable to recreate. Some designs were so skillfully done in their complexity that Johnson didn’t know how they were done in the first place.

Reproductions are also important, Wright says; because they support scholarship for those who can’t see the originals by providing a viewer with a three-dimensional sense of what an original looked like. Further, they help create new forms of scholarship like medievalism, the study of how the medieval ages have been studied, interpreted, and reimagined in pop culture. What do these objects mean to us after the fact? What is their continued significance? How are we using them for our own purposes in today’s world? These are just some of the questions medievalism hopes to answer. These questions are very intriguing because some of the original pieces of these reproductions, like the Tara Brooch and Book of Kells, have political and culture significance, due to their association with Irish nationalism and independence.

To learn more about Gaelic Revival, medievalism, and the pieces themselves, the exhibit is open to the public free of charge until April next year. The Grand Opening took place last Friday, September 23rd, and featured a lecture from Charles Wright, as well as other speakers, food, and an Irish music concert.

In addition, an All-day Symposium will take place on October 1st. The symposium will feature talks from scholars from all over the U.S. and the world who are specialists in the medieval period or reproductions themselves.

On October 2nd, there will be a film showing of A Terrible Beauty. Free curator-led tours of the exhibit are being offered on December 3rd and March 5th. Numbers are limited, so contact Kim Sheahan at 217-244-3355 or ksheahan@illinois.edu to reserve a spot.

A full schedule of events related to the exhibit can be viewed here.

Charles Wright can be reached at cdwright@illinois.edu with any questions.

Photos courtesy of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.