S is for studio. The place where an artist works. Thick paint takes its course on canvas. Lush clay finds form and personality. A silver fork bends into loops and curves.

The place and surroundings are important, but it’s the commitment to being there that’s critical. The need to claim a physical space and dedicate it to creative pursuits is what I’m exploring with this meandering “S” — and so I asked five local artists where and how they focus on their work. Each studio holds its own incantation of space, mood, accessibility, and opportunity. And each artist has particular ways of inviting the Muse.

Don’t we all long to spend time with our small flame of creativity, undisturbed by Daily Stuff? Let this be an inspiration for looking at how you might claim that moment for yourself.

One sunny afternoon I drove into the forested edge of east Urbana, crossed I-74 and turned into the driveway of High Cross Art Studio. The building is a simple warehouse, but the surroundings are trees and meadow, quite different from the Champaign Urbana I spend my days in. Entering the door, I immediately responded to the light, the high ceilings, the open expanses. It’s like a clean canvas inviting work.

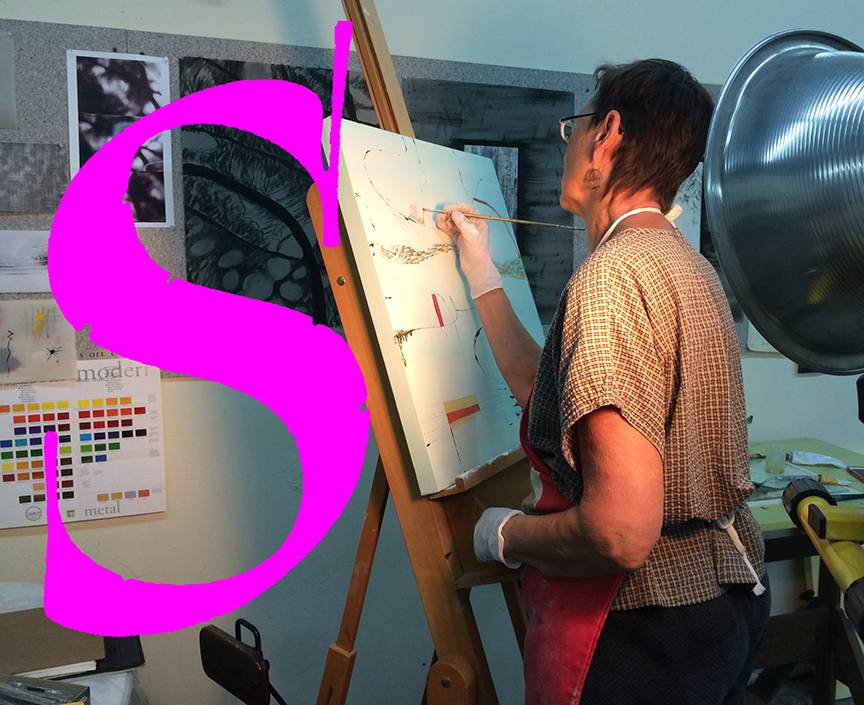

Viktoria Ford has her studio there. She is a veteran student, teacher, and curator as well as prolific painter and wire sculptor. She has moved past the studios of classroom days and corners carved out of various homes. She now rents a space in this building with its accumulated karma of art across many years. In the 1980s Ford worked for Frank Gallo there when he orchestrated a team to construct large productions of his cast paper works, blown glass, and also work for Erté and Vasarelli. The building supported innovative and expansive work then and still does, today housing a collection of painters, ceramic artists and sculptors.

It has what Ford seeks in a workspace: a place to be her own person, to think, to accumulate books, ideas, and sketches. A place for tall easels, large canvases, unfettered thinking. A concrete floor comfortably splattered with zigzags of paint. A wide sink. Storage. The inspiration of other artists’ sounds and workings.

For Ford, making art is an essential part of the day. It takes her on a journey that engages her mind, her hands, her eyes, her unconscious. It opens a place to take risks, make mistakes, create a world of her own imagining. In her words, “As artists we are visual philosophers. We take in the world of experiences, we digest these experiences and then some indescribable and unrelenting need takes over that demands processing through the act of making art.”

And what a beautiful place she has to work in. A door from her studio opens onto grass and trees, birdsong and sky.

Ford is currently working on a series of paintings that explore local waterways, their origins, evolution, and fragility. “The Journey” is part of that series.

It’s well worth a visit to Ford’s website, a thoughtful and intriguing exploration.

Another creative space in Urbana goes farther in sharing equipment, expertise, and energy. For a number of years the Champaign-Urbana Potters’ Club has resided in a storefront at the corner of Race and Washington streets in Urbana. It’s an orderly, light-filled space with a number of wheels, a large working surface and sink in the front room, storage and personal space behind. The club focuses on pooling their resources for purchasing, organization, education, and inspiration. They bring in teachers for workshops such as raku techniques.

For Stephanie Sutton, who has been a member about ten years, a central advantage is its accessibility, both in location and hours — it’s open to members 24 / 7. Equipment includes electric wheels and a kick wheel, several kilns, a slab roller, varied glazes and clays, and shaping tools. Sutton particularly appreciates the sink that collects clay particles for re-use.

Perhaps the greatest resource for members is their shared expertise. Sutton has seen the level of members’ work rise over the years. Each contributes pieces for group sales that help pay their costs. I first got to know their work from their annual booth at the Taste of Champaign.

Members contribute their expertise to good works as well. For several years the club has orchestrated Empty Bowl, a fundraiser for Daily Bread soup kitchen. Between them they donate 300 one-of-a-kind bowls, to be filled with soup at Silvercreek Restaurant. Contributors enjoy dinner and a bowl to take home — a most creative community repast.

The experience of working in clay has opened a new world to Sutton, who comes from a technical, business background. She enjoys the hands-on time and the meditative concentration it brings, in centering a piece of clay on the wheel and creating a harmony with her hands to shape a finished piece. Like all creative processes, the outcome takes its own turns depending on the variables throughout: the moisture in the clay, the shape it’s inclined to take, the inspiration of the day, then two firings and glazing. Opening the kiln at the end always reveals the unexpected. The promise begins with simply opening the door off Race Street and entering well organized working space and energy, away from home and daily distractions.

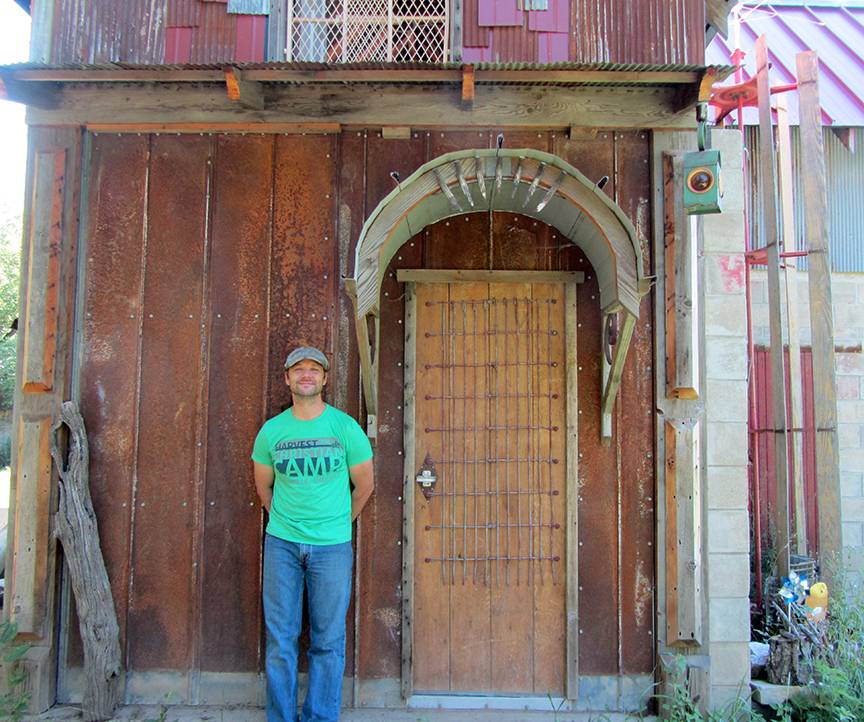

Then there is the above-and-beyond-the-normal-range-of-sanity drive to create an inspiring and functional workspace. Unusual inclinations and skills call forth unusual construction. Such things flutter off the fingertips of Tony Taylor, sometime welder, metal worker, woodworker, cabinetmaker, museum exhibit fabricator, electronics pro. And musician — primarily a drummer. Tony has messed around with all kinds of instruments since he was a child. He’s fascinated by making his own.

Taylor creates unique guitars and more from all kinds of found objects: vintage cigar boxes, yardsticks, spoons and forks, pie plates, keys and keyholes. He works under the name Ascendent — “moving up and moving forward” — and that’s what he does. He never was attracted to high end guitars with their clean modern sound. For him, the home grown warmer tones that rise out of the musician himself are what he connects with.

Taylor’s instruments are primarily 3-string guitars, the next step after the traditional homemade one-string diddley bow. They tune to A-E-A, which gives a root chord, a fifth, and an octave, the basis of an American sound profoundly different from the European 6-string guitar and tradition.

Taylor’s home is on farmland in Potomac, about 45 minutes northeast of Urbana. For the growing business that comes largely out of the Urbana farmer’s market he needed a place to work. There happened to be a cement slab on his land that measures 10′ x 21′ — and one thing led to another. 500 concrete blocks from an old Walmart building were up for grabs, and the rest took its own shape, right up to the cupola — his dream — and the lightning rods on top. Taylor built most of it himself, over the course of a year. The ground floor accommodates the wood work of sawing and sanding; the upstairs is clean for electronics.

Everything about the studio is home-built and surprising, from the two-barrel woodstove to a rescued school blackboard for notes and messages. The idea is to keep it fun. And I’d say he’s succeeded. Walk in the door of this studio and you are immersed in the raw materials of exceptional ideas and the instruments that grow out of them.

I was first drawn to Brian Kerlin’s booth at the Urbana farmer’s market by the sweet tinkling sounds from his mobiles. And once I saw what they’re made of, I was fascinated. Forks, spoons, and knives are transformed into whimsical and beautiful shapes and strung together by his partner Joann with glass beads, shells, and unexpected bits of fancy. There is artistry and skill in both the patterned silverware and how Kerlin shapes them, from the mobiles to creatures like snails and turtles, budvases, and a great case of rings shaped out of spoon handles.

Kerlin graciously opened his studio to me, along with his impressive knowledge of the decorative silverware he has collected over the years. He works at a compact and efficient workbench in a corner of his compact and efficient home in east Urbana. For the specifics of working with silver, he makes or adapts most of his tools, filing down the teeth of double-action pliers to suit the precise moves for curving silver pieces. He does much of his work with a heavy cast iron forming tool, using thick pieces of leather to protect the silver while he’s bending it.

Kerlin’s working corner is a pragmatic space, but his wit and whimsy are evident. His inspiration surrounds the workbench.

He characterizes his work as more craft than art, in service to the beauty of the silver patterns. Kerlin told me the story of souvenir silverware. When Ford’s Model T opened the door to an affordable automobile for American families in the early 1900s, the road trip became the favored vacation — and it grew a culture all its own. A visit to a new city was an event, and souvenirs flourished. There were many skilled silver workers on the east coast who lent their talents to create an astounding range of patterns particular to each state and its culture. When the depression drained away the money for easy travel, the industry dried up, and the equipment was dispersed and destroyed. The techniques can no longer be duplicated. Kerlin treasures his collection of thousands of these souvenir pieces, and puts them to good use.

For him a piece of art sets its own standards. He prides himself in work to match the beauty and skill of the originals. Some of his designs, such as a spring-loaded fork bracelet, require more work than he could charge for, and are made by only a handful of artists working today.

His studio is good testimony that serious concentration produces its own results, with no frills or a special room required. And it’s clear to this visitor that just the act of sitting down at his workbench immerses him with his Muse.

———

Music as art takes a different form; after it’s played, the finished product exists only in our mind’s ear or in a digital file. To keep it alive for later listening requires space and apparatus. Sound studios have traditionally been high-end places with sophisticated soundproofing, acoustical set-ups, and big-time recording and editing equipment. But technology has reduced the footprint significantly. There are a number of recording and production mini-studios around town where our rich store of musicians produce their own recordings.

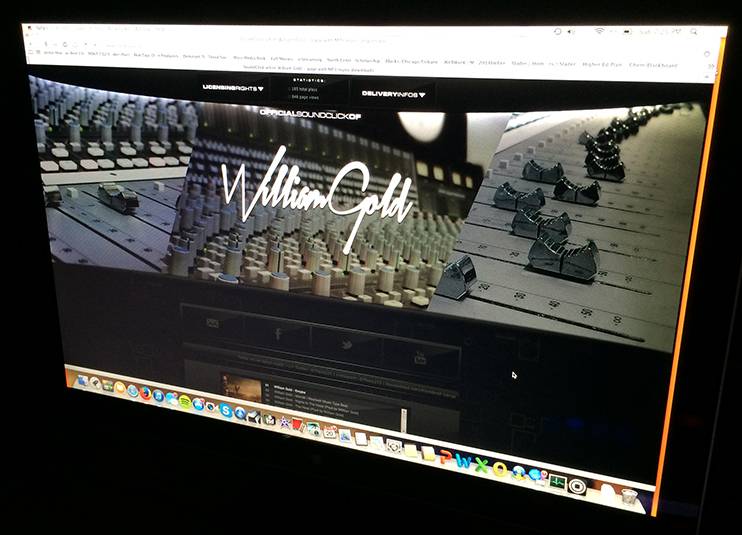

One such resides in the compact and home-based studio of Jordan Patterson in Urbana, a young and enterprising composer, mixer, lyricist, and producer.

Patterson has padded the walls and ceiling of his clothes closet and outfitted it with a microphone for recording, and has a sophisticated array of hardware, software, and instruments at a desk in the corner of his bedroom. And that’s everything he needs, to dedicate serious time to making music.

Patterson has a jazz background and plays tenor sax. He works with his own lyrics and vocals to mix his compositions, or he remixes from others’ music. He tends toward hiphop with forays into R&B.

As with all the artists and the studios I’ve visited, his inspiration relies on giving himself the time and space to explore. The keyboard is where he often starts, playing around with melodies until one clicks; and then he moves over to his preferred software, Maschine, which offers almost unlimited ways to add instruments and effects. His own recorded voice and sax are the acoustic part of the mix.

Patterson listens to a lot of new music, mostly on YouTube, where he finds work more to his taste than mainstream sources. What matters to him are meaningful lyrics and a sound that shows the artist’s own originality. In his own work he writes about what matters to him — what’s going on in his life, people’s struggles, being African-American in this country. He keeps it clean. Lyrics can take him anywhere once he starts writing and playing – sometimes into a fantasy world he’d never expected. His studio gives him freedom from outside distractions and opinions. It’s a place where he can go unafraid into unknown territory, where mistakes and multiple approaches are an important part of the process.

Patterson is a sophomore at Northern Central College in Naperville, practical about using a business degree to keep it all together, but with dreams and the tools to devote to his music. Like one of his heroes, Dr. Dre, he’d like to build his own company and someday find his place on the Lollapalooza stage. All this is possible, from a home studio carved out with care and attention, and the determination to make time for the creative process.

If you visit SoundClick online, you can enjoy Patterson’s two albums, there for the sharing, issued under his recording name, WilliamGold.

———

And for the letter S.

The early Phoenician form, Shin, comes from the word for tooth.

As with other letters, the Etruscans turned it on its side, and the Greeks developed their various forms of sigma.

With the flexibility of brush and pen lettering the corners made way to swoops and we have today’s “S”.

———

Cope Cumpston is a typographer, book designer, and community enthusiast resident in Urbana. You can reach her here: cope.c@comcast.net

The archive of abecedarian C-U lives here.