B is for bell. In this town it’s likely that you are often within earshot of one of the myriad of C-U bells that mark the hours and quarter hours. That sound reaches deep into the human psyche. It’s no wonder that our fabulist Edgar Allan Poe coined a new word to describe those moments that vibrate through your body after a clapper strikes big bronze: “… keeping time, time, time, in a sort of Runic rhyme, to the tintinnabulation that so musically wells from the bells, bells, bells, bells, bells, bells, bells… ”

They ring for big events: fires, emergencies, victories, prayers, the beginning and end of worship. They command that ultimate “For whom the bell tolls…” If it’s your day, you may be getting married or you may be passing on to the hereafter. In any case, it’s deep, loud, long, reverberant, and satisfying.

Urbana has some of the best. At the corner of Wright and Green Streets you can experience a daily concert played by your friendly local bell-ringers. And I’d encourage you to explore higher; climb to the source and encounter the bells themselves.

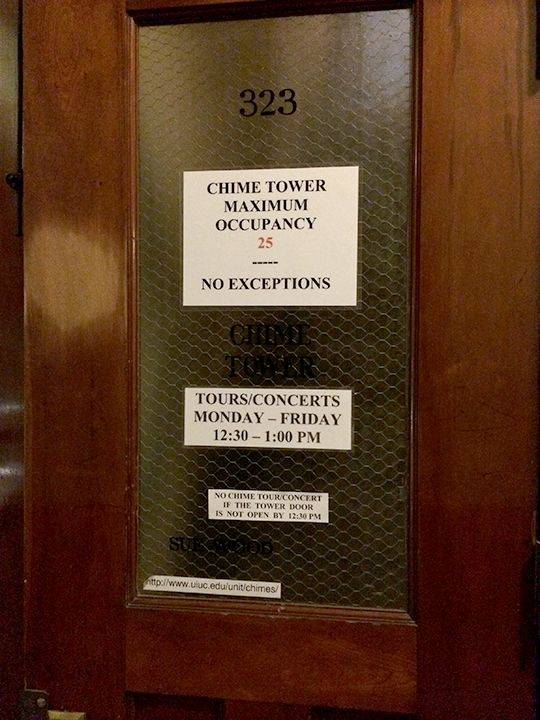

Between 12:30 and 1 p.m. on weekdays, you can make the pilgrimage up a seriously steep flight of wooden steps in Altgeld Hall to the performing room, seven stories above ground, where you’ll find the keyboard, or clavier, that plays the bells in the university’s chime. Go yet farther, up a short metal staircase and then two rather daunting vertical ladders, and you’ll step into open sky, well above the surrounding trees and rooftops. Walk around the square tower to make the acquaintance of the bells, each stamped with McShane Bell Foundry, family-owned Baltimore forger since 1856 of over 300,000 bells across America.

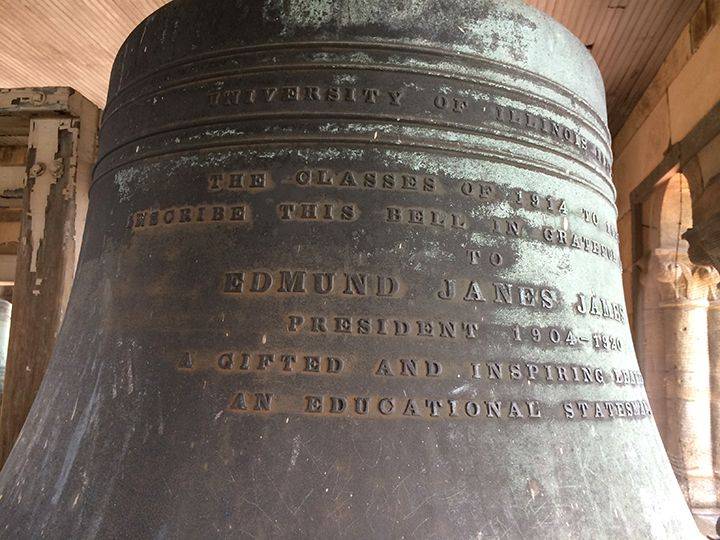

The deepest and largest bell in Altgeld, traditionally known as the bourdon, is dedicated to Dr. Edmund Janes James, president of the U of I from 1904 to 1920. It weighs in at one and a half tons, the entire set at seven and a half.

The deepest and largest bell in Altgeld, traditionally known as the bourdon, is dedicated to Dr. Edmund Janes James, president of the U of I from 1904 to 1920. It weighs in at one and a half tons, the entire set at seven and a half.

Impressive to see, but even more so to hear and feel. The quarter hours are programmed to play Westminster Chime, the complete tune at the hour and segments at the quarter hour. You’ll surely recognize this from Big Ben at the Houses of Parliament in London. It was inspired by the Handel’s Messiah standard “I Know that my Redeemer Liveth.”

The University chime is officially on the inventory of the School of Music, although its daily workings are under the careful supervision of the chimesmaster, Sue Wood, a retired chemist with the Natural History Survey. “Chime” sounds a bit minimal for 15 gorgeous bronze castings, but that’s the technical term for a set of between 9 and 22 bells. Twenty-three and over is a full-fledged carillon. You don’t have to go far to hear the 67 bells of the Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon in Springfield.

In Altgeld, there are fifteen notes to play between lower D and upper G, minus low D sharp and F natural in both octaves. The choice of precisely which 15 bells would be installed in Altgeld was made in order to cover “Illinois Loyalty.”

Chimesmaster Sue Wood at the console

The U of I classes of 1914-21, along with the U. S. School of Military Aeronautics, pooled their resources to fund our chime in 1920. They had a magnificent belfry poised and waiting in Altgeld Hall, completed in 1897 as one of five “Altgeld castles” under Illinois governor Peter Altgeldt. It was originally the university library; in 1927 was named the Law School, that name still above the front door; and in 1956 became home to the Department of Mathematics.

If you’ve never had the pleasure, I encourage you to pull open the front door of Altgeld and enter another world, another time; it’s a rare vintage experience on campus. In musty light cast by two ornate lamps at the base of the front entry is a magnificent surround of winding staircases, left and right, with inlaid marble niches, ornate wrought iron decorations, and an impressive mosaic tile floor. It’s a bit like entering an underwater chamber, with its own quality of light and space straight out of the 1890s. Take a look inside the Mathematics library at the top of the entry steps for another unmatched interior on campus.

Climb the left staircase and continue left down the hallway. During lunchtime hours you will see a door propped open, inviting the intrepid to tour the chimes.

Your host will likely be Sue Wood herself. She is an impresario of both ringing and engineering, a self-taught expert on the requirements of airplane cables, hinges, and the rather remarkable mechanisms that connect the wooden keyboard to the actual clappers some 68 feet above. You can see them in action if you’re inspired to climb up to the upper belfry during the daily concert between 12:50 and 1 p.m., confined to passing period so that classes will not be disturbed.

Wood first fell under the thrall of bell ringing at the University Lutheran Church which once had its own smaller set. She learned the art of the larger chimes in Altgeld from long-time U of I chimesmaster Albert Marien and took over the volunteer position after he retired in 1995. She wields the levers with enthusiasm and agility, playing from a wide collection of songs adapted to the specific notes of the chime, which favors the keys of G, D, and A. She welcomes anyone interested to try out the practice keyboard, which plays the notes on xylophone-like bars, so that beginners can fumble without imposing their mistakes on the entire campus community.

The practice keyboard

By tradition, every concert includes Hail to the Orange. After that Wood encourages people to play what they like, from traditional peals to Brahms, Gershwin and beyond. The current generation keeps the library up to date, including tunes from Harry Potter, Frozen, and Lady Gaga.

Several professors make use of the chime in their classes. Math professor Graham Evans introduces his students to the uniquely mathematical traditions of change ringing in Britain, dramatically described in Dorothy Sayers’ classic The Nine Tailors. [Spoiler alert: detective Lord Peter Wimsey implicates the bells in a murder… just ponder that scene…]

Prof. Evans explains that for a numbered set of bells a change begins with playing them in order and then leaps to the inspiration of whoever is directing, with each tone played once but in different orders. The versions move to the factorial, quite demanding for British campanologists, who traditionally pull their weight on real ropes to bring clapper to bell in precise time. An “extent,” or full peal, which includes the entire permutation of each bell once in every possible order, is a feat. Allowing two seconds for each tone, a full peal on 8 bells takes 22 1/2 hours.

The British have good reason for their 5,000 bell towers. In the tenth century, a decree was passed that gave the title of thane to any man who owned 500 acres, a church, and a bell tower. “Thane” was the one official position possible between a freeman and hereditary nobility.

Engineering professor David Ruzic makes a point of acquainting his students with the chime. They consider the engineering aspects of the strength of the building, the way the bells are set up, the pulley system, and the clappers and hammers. The Seth Thomas mechanism that is programmed to play the quarter-hour chime by a series of hammers outside the bells has its own fascinating piece of engineering.

Ruzic introduces his students to how bells are made and tuned if necessary, but that’s a drastic step that requires shaving the metal. And the bells must be rotated every 30 years so that the clapper will strike a different point. The intricacies of overtones and undertones are also compelling to an academic audience. As he says, pretty interesting stuff to us engineers.

Sue Wood introduced me to the complex and subtle harmonics of the bells. A bronze bell has five tones, notably the prime tone of the key it is cast to. The harmonics that reverberate beyond the fundamental frequency are one octave above, one below, the related minor 3rd and major 5th. A skilled bell ringer will take full advantage of all the tones of a well-positioned and sounded bell. The player can vary the loudness to some extent, depending on how hard she pushes the pedals, either by foot or hand. But it’s important not to overstress the cables that connect the pedals to the clappers. A repair in the bell tower is a serious thing.

The campanile on south campus is a recent addition, and not a happy one to those serious about their traditions. It has 48 bells, a full 4-octave carillon, cast by the Royal Bell Foundry Petit and Fritsen, operating since 1660 in the Netherlands. But the money was not raised to include a full keyboard console, and the playing is controlled by a remote system. And to a sensitive ear like Wood’s, the tones of the bells are not what they should be, most likely because of the position of the clappers, which should center solidly at the wide base of the cup.

Other bells in town have their own stories. A particular tradition is carried from the belfry of Emmanuel Memorial Episcopal Church on the corner of State and University, overlooking Westside Park in Champaign. It is programmed to ring the Angelus, known for centuries through the fields and streets of Europe as the call to prayer at the designated hours of 9 am, 12:15 and 5:15 pm. At other quarter hours they ring the Westminster Chime, the same as Altgeld, like the county courthouse in Urbana, whose bell tower was restored in 2009, complete with gargoyles. None of our other town belltowers however approach the size and versatility of the Altgeld chime.

Millet’s 1859 painting, The Angelus, with a bell tower in the background

Handbells have their own mystique

A number of churches around C-U have bell choirs. I was warmly welcomed at a rehearsal at the First Presbyterian Church in Champaign, skillfully directed by Karin Vermillion. This is a 5-octave choir of hand-held bells. A full complement of players for this particular set is 13 people, who each handle between 3 and 8 bells. That can become quite a juggling act, I know from trying it myself. There are a number of different techniques to master: swinging the bell from the shoulder at the right angle to strike the clapper, striking it with a mallet, plucking, thumb damping, and more. You can see the intent concentration on the faces below.

The sound of a full handbell choir is an ethereal thing. I was charmed by the enthusiasm, skill and dedication of the First Presbyterian ringers.

The world of bells may seem a far cry from the digital precision of our smartphones and computers — and yet they all work their way back to Greenwich Mean Time. The passions of the bells and ringers in C-U provide an invisible and steady encouragement through our daily rhythms that is a memorable piece of the local infrastructure. In Wood’s early days in the Altgeld bell tower there were 1000 visitors each year; that has steadily increased under her enthusiastic guidance to 2300 in 2013. She provides each pilgrim a printed history of the bells and a chance to ring the real thing. There’s an unfailing and gratifying look of wonder from each person sounding those bells for all to hear.

——————————————————————————————————————–

On to the letter “B.” The 2nd letter of our Latin alphabet has a visible progression, with its origin in the word for “house”

from the Egyptian hieroglyph

to the Phoenician form

and Etruscan beth

which reverses to our Roman B.

The Hebrew bet has the same origin

And for western abecedarians “bet” is the chosen partner to “alpha” so that alpha-bet stands for our entire 26 letters.

Cope Cumpston is a typographer, book designer, and community enthusiast resident in Urbana. You can reach her here: cope.c@comcast.net

The archive of abecedarian C-U lives here: