You can see Abraham Lincoln’s image today on license plates from Chicago to Carbondale, but the heart of the Land of Lincoln is Central Illinois. The recently published book People and Places in The Land of Lincoln by retired Millikin professor Dan Guillory is a tour guide of Lincoln’s Illinois stomping grounds for anyone serious about learning about the people and places that shaped our 16th president. Although the book covers areas as far south as Vandalia, much of it focuses on Springfield, where Lincoln lived for 25 years, and on the counties in Central Illinois Lincoln knew from his days as a traveling lawyer on the Old Eighth Judicial Court.

You can see Abraham Lincoln’s image today on license plates from Chicago to Carbondale, but the heart of the Land of Lincoln is Central Illinois. The recently published book People and Places in The Land of Lincoln by retired Millikin professor Dan Guillory is a tour guide of Lincoln’s Illinois stomping grounds for anyone serious about learning about the people and places that shaped our 16th president. Although the book covers areas as far south as Vandalia, much of it focuses on Springfield, where Lincoln lived for 25 years, and on the counties in Central Illinois Lincoln knew from his days as a traveling lawyer on the Old Eighth Judicial Court.

People and Places in The Land of Lincoln is well written, easy to read, and exhaustively researched. Need a recommendation of a good itinerary for exploring Lincoln historical sites in the New Salem area? Or want to read about Springfield government official James Matheny, who was the best man at Lincoln’s wedding? Then this is the right book for you. People and Places in The Land of Lincoln also has a number of sections about Illinois in the 19th Century in general that provide the reader historical context.

I spoke with Guillory recently in Champaign. He warned me at the start of our conversation that his book is “not about Lincoln per se, but about the people and places in Lincoln Land,” but it’s hard to interview a Lincoln expert without talking about Lincoln’s presidency. I didn’t even try, and I learned that there are many links between things Lincoln said, did and experienced in earlier in his life in places like Shelbyville and Sullivan, Illinois to the great events of the Civil War era that came later.

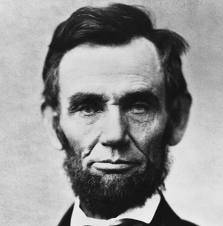

A guy who really liked being photographed

Guillory writes about how Illinois changed in the 19th Century from frontier to settled. In 1818, when Illinois became a state, there were still enormous expanses of native prairie grasses and wolves were a nuisance to settlers. Half a century later the prairies were plowed over and the wolves were exterminated. Guillory explained, “By the end of the Civil War, there was virtually no free land in Illinois, and that’s when people started going over the river.”

Lincoln, who was born in 1809, lived through this period of change. It was a time when women died frequently from childbirth, diseases like milk sickness (which killed Lincoln’s mother) were a risk to everyone, and winter weather could easily be fatal.

My guess is that new technologies of this time like John Deere’s polished steel plow—which made it possible to farm the prairie lands on a greater scale—and the new-fangled camera, were seen by settlers as progress against hostile nature and as a symbols for the hope of a more comfortable future.

Guillory writes in his book, “In the 1840s, portrait photographs were a mark of status and modernity. Lincoln loved all the new inventions, and he was photographed more often than any other public figure of his day.”

Lincoln, who was into mechanical things in general, also took out a patent for an invention of his own, a device for moving boats. Guillory said to me that if Lincoln were alive today, “I think he would love laptops.”

Another fascination was railroads, which by the 1850’s were changing the country. Guillory said of Lincoln and the iron horse, “Railroads were the big transformative engine—no pun intended. Lincoln was the first politician to really use the railroad effectively and did a lot of campaigning all over the country before the presidential campaign. Just giving speeches and getting himself on the map. He loved the railroads.”

Another fascination was railroads, which by the 1850’s were changing the country. Guillory said of Lincoln and the iron horse, “Railroads were the big transformative engine—no pun intended. Lincoln was the first politician to really use the railroad effectively and did a lot of campaigning all over the country before the presidential campaign. Just giving speeches and getting himself on the map. He loved the railroads.”

I asked Guillory if Lincoln’s faith and fascination with technology faltered once the Civil War started and the advent of new weaponry like repeating firearms allowed soldiers to kill one another in much larger numbers.

Guillory responded that “no one on either side expected” the sheer horror of the war. He also said, “I don’t think anyone anticipated that the war would last four years. For the United States, the number of people killed relative to the total population was awesome.”

However, Guillory told me that Lincoln’s biggest failure to predict accurately wasn’t in how devastating the war would turn out to be, but that it started the way it did: “He really thought the South would not attack. He thought it was all bluster. The reason he thought that is he really didn’t have good political intelligence and he didn’t know the South was arming.”

A self-taught man

Lincoln, an avid reader who had very little formal schooling in his youth, pretty much taught himself. A lot of his learning took place in New Salem in Sangamon County, where Lincoln spent much of his twenties. During his time there, he taught himself law, among other things.

Guillory said, “Here he was in this little village of New Salem, just a couple hundred people, and he manages while he’s there to teach himself trigonometry, really nail down the King James Bible in his own mind and engage in a debating society. He taught himself to survey and he learned Shakespeare. I think he was very open to new things. That applied to all his thinking.

“I would see that as a larger pattern of taking advantage, in a good way, of the opportunities that were there.”

Guillory continued, “He even wrote an essay on Atheism, which he subsequently destroyed since it could get him in trouble.”

I asked Guillory about Lincoln’s religious beliefs. He responded, “People get upset when I give talks and tell them this, but Lincoln was never a Christian. He never believed in the divinity of Jesus Christ. But he did believe in predestination.

“He would have been a Deist very similar to Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.”

According to Guillory, Lincoln’s faith was more in the Founding Fathers: “For Lincoln, the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were ultra religious documents. He fundamentally believed in them and felt they ultimately set the law of the land. There’s a famous story that, well into the war, a general came into his office and said, ‘Oh sir, we’ve just captured some of their territory.’ And Lincoln got really angry and said ‘No, it’s all our territory.'”

Guillory told another story of Lincoln and a different general to further illustrate Lincoln’s beliefs: “During the war one of the generals said something like, ‘Well God must be on our side because we won this battle.’ Lincoln said, ‘We don’t know whose side God is on, but there must be some meaning to this.'”

The son of a dirt farmer from Kentucky

Lincoln’s father was a hard working, if not spectacularly successful, farmer. He thought his son spent too much time reading. He moved the family to Indiana and later Illinois in part because of financial difficulties. In short, Abraham Lincoln’s socioeconomic background wasn’t one that anyone at the time would have expected to produce a president of the United States.

I asked Guillory if Lincoln was ever insecure as he became more powerful and rubbed shoulders with leaders from Ivy League backgrounds. Guillory responded, “I think there was a sense of insecurity all his life, although probably not during the last years of his presidency so much.”

In contrast to Lincoln, his wife, Mary Todd—the couple were married in 1842—came from a politically connected and wealthy family. Guillory said of Mary Todd, “She was well educated. She knew where to put the forks. She could speak French fluently.”

Lincoln’s in-laws looked down on him. Guillory told me that their attitude didn’t really end “until Lincoln was president and they were looking for appointments.”

Lincoln’s relationship with his wife was often troubled. Mary Todd is said to have clocked her husband in the head with a piece of firewood for paying more attention to what he was reading instead of her. Guillory told me, “She went after him with a butcher knife one time.”

So what was her effect on her husband, politically and personally? Guillory told me that it was by no means all bad: “She was an unflagging supporter throughout. She believed in him. Everyone thought she was crazy, but she believed, way back when, back when no one thought it was possible. And when he did finally get the nomination and was elected president, she played the part of political wife very well.”

Guillory believes that Mary Todd suffered from mental illlness, which was even less well understood then as it is now, and it didn’t help that her husband was obsessed with his work. Guillory said, “With some Prozac Mary would have been totally different. She needed some help that was not available at the time. And she was raising kids by herself.”

However, Guillory said that Mary’s role as a political wife basically ended when the couple’s son Willie died of fever at the age of eleven during Lincoln’s first term as president. He said of the death, “It divided the marriage and put a pall of gloom over that house that was not lifted at all. It was said that Mary just basically locked herself for about a year.”

He added, “They needed to help each other as a couple, and that ended.”

Despite it all, Guillory said he believes that the two really loved each other.

A speech that would work?

One section of the book covers Lincoln’s activities in Charleston and Lerna. Charleston was the site of one the great debates between Lincoln and Stephan Douglas during the 1858 Senate campaign. Guillory writes that over 12,000 people showed up to hear the two candidates debate the slavery issue.

12,000 people to hear a political debate? In Charleston? I asked Guillory how the audience was even able to follow along in a time before modern PA systems. He responded that part of it was that the audience was just listening really hard: “It’s hard for us to believe in an era of cell phones and people just chattering and so forth, but in that era going to these speeches was like going to church. People paid rapt attention and I think they just craved the sound of the language. And politicians were expected to give long speeches.”

I wondered how this expectation of long speeches fit in with the Gettysburg Address, which came about five years later, and ran about two minutes in length. Unsurprisingly, Guillory is a big fan of the Gettysburg Address. He said of the famous speech, “It’s concise, it’s totally sincere; the rhythm alone carries it. How did someone write that? And no he didn’t write it on the back of an envelope.”

But why did Lincoln, a consummate politician, end up giving a two minute speech on an occasion when a shaken audience expected one that went for hours? What about the risk of coming across as disrespectful to the soldiers who died on the battlefield and their families? Was it nerves? Desperation? Anger?

Guillory responded, “I guess the short answer is, I don’t know, but I can tell you what I think: it was coming obviously after the three days at Gettysburg and the victory at Vicksburg. Grant was in control, but there was still a lot of fighting ahead.

“There’s a creek that runs right through the whole battlefield, and they say that it literally turned red. Even when Lincoln went there to dedicate it, there were still dead bodies. They’re still finding lead bullets today.”

Guillory continued, “I think he was probably moved. It may have been that he was simply unable, from all the pressures, to draft a longer document.

“It may have been that Lincoln, in his own mind, chose to define this as a religious moment rather than a political one. So that what he was going to say was going to be some kind of prayer. He uses words like ‘consecrated’ and I think he saw himself there as more of a priest than a president.”

Guillory noted that it wasn’t that Lincoln had lost his ability to give long political speeches, since he did so for the 1864 presidential campaign, however, “He couldn’t, or chose not to, for Gettysburg.”

Compromiser into Emancipator

Lincoln the Illinois lawyer and pre-presidential politician was not a hardcore abolitionist. Guillory said, “What he was hoping was going to happen was that slavery would just die out. This was why he was so opposed to the extension of slavery in Kansas and Nebraska which was proposed by Stephan Douglas.”

How does this attitude fit with the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, which ended slavery in the Confederate states? While not a total abolishment of slavery by any means, Lincoln’s two executive orders were a very strong statement for a politician who was less extreme on the issue than abolitionists like John Brown and Frederick Douglas.

Guillory said that one of the things that held Lincoln back from doing more to end slavery sooner was that he wasn’t sure he had the legal right to do so: “The abolitionists wanted him to emancipate the slaves from Day One.

“Just as he thought the South had not right to secede, he thought that he had no right to abolish slaver,y too, because it was written into the Constitution.”

However, Guillory said Lincoln eventually found a way to justify the Proclamation on legal grounds: “Somewhere along the line Lincoln realized that the Commander in Chief has the right to make decisions that may be unconstitutional, if they are justifiable on the grounds of military necessity and protection of the country, and that’s the loophole through which came Emancipation.”

Guillory continued, “It was only by justifying it as a military necessity. And it was; in fact, a lot of the northern soldiers and politicians, to say nothing of the southerners, were infuriated that he was arming black people. But Lincoln wanted to free the slaves first of all to take away the power of growing things in the South, but secondarily to arm slaves that were freed.”

Guillory also made the point that the Proclamation may not have mattered as much as some historians believe, since slavery was ending anyway on its own accord as the Confederacy collapsed and abolitionists and slaves grew more organized. He said, “The Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free a single person, because it freed people who were under control of the rebels. So they freed themselves in large numbers as the lines grew shakier, and people figured out that there were all these underground railroads, including one that ran roughly right between Decatur and Springfield.”

A country boy at heart?

Lincoln was someone who spent a lifetime trying to get away from the hand-to-mouth lifestyle of his father’s farm, and he did. For instance, Guillory mentions in his book that Lincoln once earned a $5,000 fee (an enormous sum at the time) working as a lawyer on a case for the Illinois Central Railroad. However, the man who sometimes acted as a high-powered attorney for corporate interests (he also represented common people as well on many occasions) wound up with a folksy “Honest Abe” and “Railspitter” image that endures to this day. Did the country boy image ever annoy Lincoln?

Guillory said, “I don’t know if he ever worked those contradictions out.” He continued, “The Illinois that Lincoln knew in the 1840s was in many ways totally different from today. And yet, if you put Lincoln on a horse in Petersburg, I think he could find his way around without using the Interstates. He’d still recognize all the creeks, landforms and certainly all the trees. He was a woodsman after all. He loved the Illinois and the Sangamon Rivers.”

I asked Guillory what Lincoln would think if he were alive today of prairie restoration projects. Would he approve of places like Meadowbrook Park in Urbana? Or, would a man who grew up in a period where plowing the prairies was seen as progress not get it. Guillory responded, “It’s kind of complicated. I think he’d be in favor of it. You have to understand that, in some ways, Lincoln was a green politician. He did not own a firearm; he did not believe in shooting animals. He was very tenderhearted towards animals. There’s a famous story, a documented story, that Lincoln was riding by in Illinois with some other lawyers and there was a pig caught in a fence squealing and Lincoln couldn’t stand it. After about a mile he turned around and went back and got the pig out of the fence.

“I think our concepts of ecosystems are pretty modern. Lincoln probably didn’t know a lot of Botany; he knew a lot other sciences, but not Botany. But he certainly had an appreciation of the land.”

Conclusion

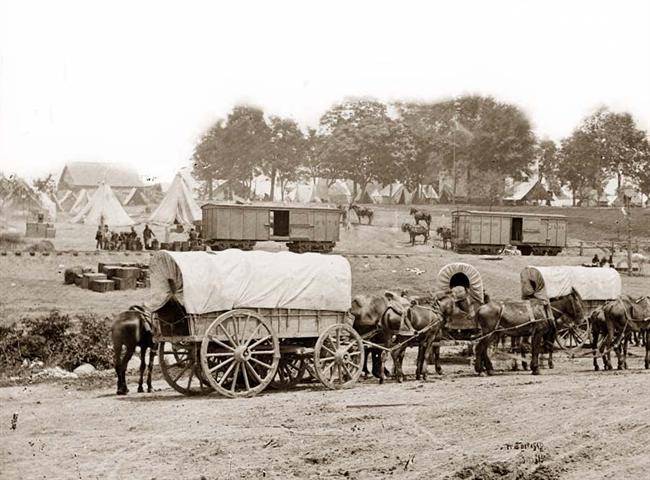

If there’s a theme that ties together Lincoln, his times and 19th Century Illinois, I’d say it’s transportation. Lincoln came to Sangamon County as a 22-year-old in the 1830s by canoe, traveling from Coles County via the Sangamon River. Illinois was about rivers then: the Mississippi, the Illinois, etc. It was the golden age of steamboats and the young state was still frontier.

Lincoln returned to Sangamon County as a slain president by train in 1865. By then, railroads had transformed the country and allowed agriculture on the prairies to be practiced on a larger scale. Illinois was an important and settled state in a union that I’d say Lincoln, as much as anyone, saved.

People and Places in the Land of Lincoln, which is available at Jane Addams Book Shop in Champaign, can help anyone better understand Lincoln and the state where he spent most of his life.