My eyes and ears have been drawn to the universe of the digits, zero through nine, by a few intriguing encounters in our beloved Champaign Urbana, where someone is always up to something. And before I know it, one door leads to another.

Grab your mittens and hat, maybe an umbrella, and come along to enjoy what the creatives are doing with numbers. I’ve immersed in the gambits of both number whisperers and mathophobes. They are finding they have more in common than they suspected.

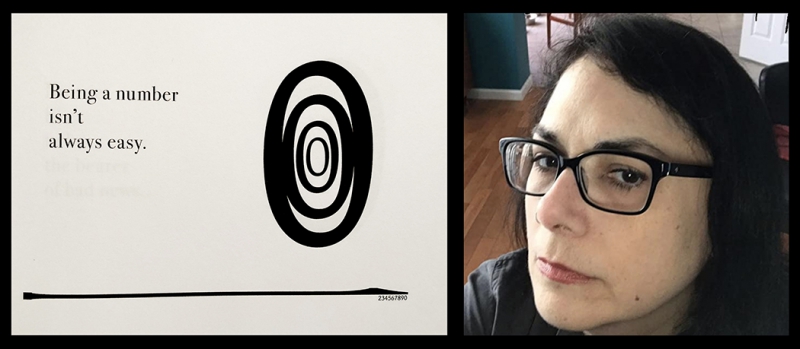

As a word person myself, I began at this year’s Small Press Fest, where I was intrigued by a book by Debra Domal, artist, graphic designer, arts editor of Smile Politely, as well as recovering New Yorker, bagel snob, and BuffyVerse devotee. She recently birthed Confessions by Numbers (The Coronavirus Edition), which led to The Number Stories Project. This may be unexpected from someone who considers herself firmly on the side of words and art versus numbers, but she grew up with an accountant father who smiled wisely and told her that numbers always tell a story. She inherited from him a number of handsome ledger books, and wanted to find the right project to establish common ground between her world and his.

©Debra Domal, Confessions by the Numbers, 2020.

The long hours of pandemic isolation have spawned quite a few enterprises. Confessions by Numbers was Domal’s creative response to her daily confrontation with the numbers newly dominating the daily headlines — how many new cases, ICU occupancies, and ultimately, deaths by COVID? Were the numbers rising or falling? They had the sudden power to shape our daily reality. Domal gave them the benefit of the doubt with the opening: “It isn’t always easy to be a number.” She took a deep breath and gave voice to the numbers themselves, in the words she imagined they might say to “confess their fears and share their hard-won wisdom.” Each sentiment is matched with a graphic made with numbers themselves, right side up, inside out, even flowing in the shape of an angel’s wing.

©Debra Domal, Confessions by the Numbers, 2020.

Treat yourself to a ramble through her imaginings. In town, you can pick up a copy at Art Coop in Lincoln Square.

After the book came out she was intrigued with the idea of inviting the community into a larger conversation. With a grant from the Urbana Arts & Culture program she created The Number Story Project. What’s the COVID story you could tell about numbers — in poetry, text, or graphics — for the collective “remembering and healing from our experiences of the crisis.” Look for an upcoming display about the project in the windows of the Art Coop.

With numbers fresh in my thoughts, on a recent visit to Urbana’s Market at the Square I was drawn to the glowing shapes and colors of Kathryn Swift’s hand-cast Dragon Ink Dice, designed to delight gamers.

Photo by Cope Cumpston.

What a compellingly beautiful showcase of numbers. New to me is the variety of the dice — with different numbers of facets described by “d” indicating how many sides the die has. A D&D set consists of seven: one each of d4, d8, d12 and d20, with two d10s.

Swift’s game of choice is Vampire; her father is a Dungeons & Dragons devotee. He concocted a plan to celebrate the numerical happenstance of January 20, 2020 with a D&D challenge on Twitch, and mentioned that it would be ever so cool to have custom dice. She had just gotten a job in a bookstore that shut down due to COVID. What better use of her time than to delve into the technology, art, and mystery of diecasting.

Photo by Cope Cumpston.

She’s perfected her technique over time, using a font designed by Elizabeth Komer, a member of her Facebook dice group. She starts with a 3-D printer for the masters, makes silicon molds from these, pours in resin, and puts them in a pressure pot for a 6-hour cure. The materials are toxic; they require a respirator and nitrile gloves along with a well-ventilated room and strong filter. For finishing, the dice can go in a tumbler, but mostly she polishes them by hand with Zona papers. Colors and special effects are limited only by ingenuity; she uses the glitter in eyeshadow, acrylic paint chips, and has even embedded charms or baby’s breath for special projects. Swift is drawn to the combination of art with function; these luminous dice add that certain something to a gamer’s experience.

For a bit of an intro to just how random numbers weave their way into fantasy and warfare, I called on friend and D&D enthusiast Sam Snyder. Dungeons & Dragons, designed in the 1980s, was the groundbreaking model for all role-playing games to follow. It’s essentially a grand improv in a world populated by dwarves, elves, halflings, humans and far more. Players develop a character and imbue it with the attributes of strength, dexterity, constitution, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma, the amount of each specified by a roll of the d20. Then specific dice in the set of seven are rolled for the quality and quantity of weapons, armor, gold pieces, and all action to come. The specifics of the story and how the characters interact is up to the ingenuity of the Dungeon Master. Small hints from the introduction to The Players Handbook hint at the possibilities: “A tall human tribesman strides through a blizzard, draped in fur and hefting his axe…A half-orc snarls at the latest challenger to her authority over their savage tribe…Frothing at the mouth, a dwarf slams his helmet into the face of his drow foe.” You get the idea. At each question in the storyline, the rules indicate a throw of a specific die, and the numbers, from low to high, indicate the strength or success of an attribute or a play. The Dungeon Master then paints details around the number to enrich the story of each campaign.

Photo by Cope Cumpston.

The dice introduce an element of randomness to the story, but since each player throws them for their own character’s attributions and actions, they give a feeling of agency. Life or death, what are the odds? To Snyder, the dice add a storytelling tension. It’s ultimately a game with a considerable amount of philosophy. Chance and the numbers add their certain electricity.

Let’s look at the essence of the numbers: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10. Humans have ten fingers, and there’s no accident that the numbers and the fingers are both called “digits.” Our language and communication and thought systems start with the human experience. Teach a child to count, and it’s one finger after another. The earliest known artifact indicating counting is the Lebombo Bone, showing 29 notches, dating from 35,000 B.C. It’s likely that growing populations and need for more resources led to trade, and that encouraged systems of computation. With reliance on agriculture, prediction of the seasons and divisions of time were desirable. Human ingenuity and the delight of a challenge led to numerical analysis of the movement of stars and planets, measurement systems, and far more that we find evidence of in past civilizations. Written mathematical notation dates from the Sumerians around 3000 B.C. “Numbers” leapfrogged past mere digits to elaborations of positive and negative, rational and irrational, real, complex, and beyond.

Photo by Cope Cumpston.

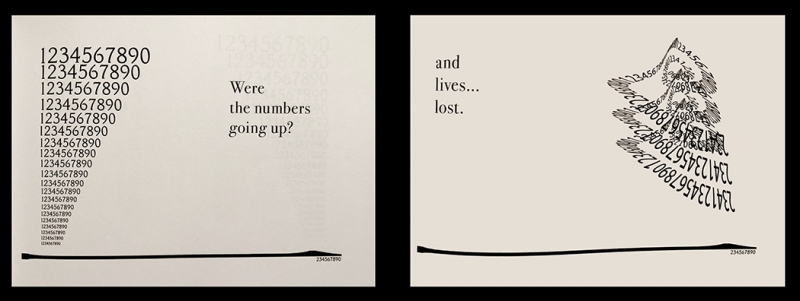

For an informed introduction to the scholarly discipline surrounding numbers, I found a generous guide in Professor Bruce Reznick of the Math Department, resident at Altgeld Hall. He is known for his skill and devotion in teaching “elementary number facts” as well as more elevated and esoteric mathematical analysis. One high level solution awarded him with his portrait on a beer label. Forgive a brief sampling of the lingo.

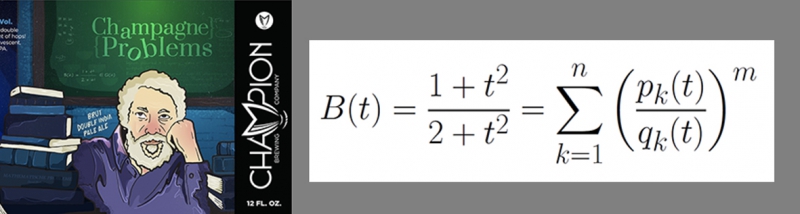

A longstanding mathematical challenge by Eberhard Becker is known as the “Champagne Problem.” He proved that for every even integer m, B(t) can be written as a sum of the m-th powers of rational functions with rational coefficients, and challenged others to provide specific examples. Reznick wrote the formula you see below, which shows the exact example of the smallest case, in degree four.

Start with a brewery with the goal of developing a brut-style IPA, its own “champagne problem,” an operations manager who has an advanced degree in mathematics, and some unlikely threads converged between a longstanding mathematical challenge, a recipe for beer, and a sophisticated solution provided by a professor living in Champaign. Here is one celebration of numbers.

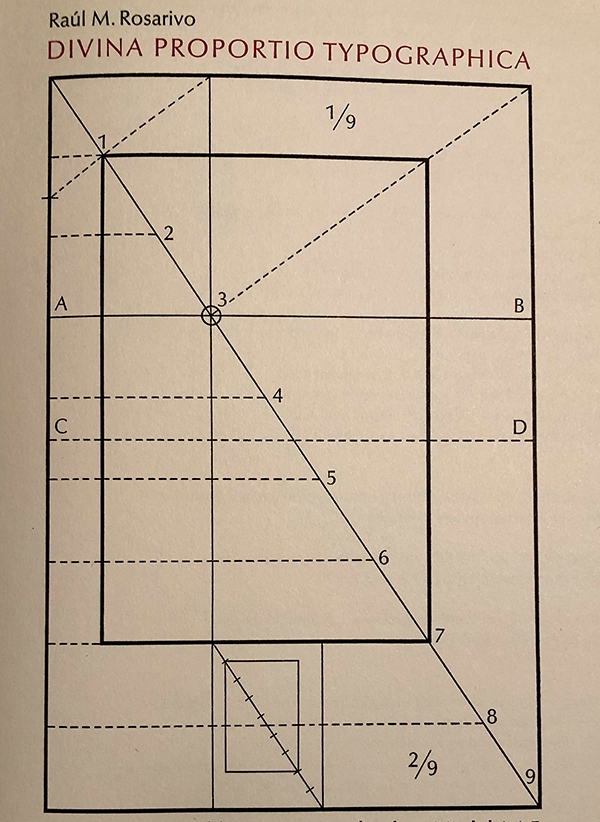

Reznick is just as drawn to the simpler puzzles and patterns that mathematics is singularly equipped to elucidate. From early childhood he was fascinated by numbers and the challenges of finding patterns with them. For him the nature of a mathematician’s research is trying to answer questions; in seeking out a promising challenge, he looks for a “natural” question, one that can be described simply. A favorite is the Fibonacci series, whose numbers are the sum of the previous two, 1-1-2-3-5-8-13-21 and onward. This series describes the growth of the whorls of the seeds in a sunflower head, and the bracts encircling a pine cone. As the numbers grow larger they approach a ratio known as the Golden Section, long considered an aesthetic ideal visually and rhythmically. It is shown in the proportions of the Parthenon, architect LeCorbusier’s Modulor, musical compositions, and even the proportions of text to margins in book design.

Image from Hermann Zapf / Maximilian-Gesellschaft Hamburg.

Reznick caught my attention in referring to Bach’s explorations of patterns and variations in composition as embodiments of the mathematical concept of QED, “Quod erat demonstrandum,” meaning “that which was to be explained.” The natural and satisfying conclusion of a progression of musical notes shows the same resolution as a mathematical proof. Our western music is indeed grounded in the numerical system of the seven notes in an octave, and the harmonies established between different intervals. A satisfying song involves the patterns of both predictable and surprising numerical intervals.

There are some believers that numbers can indicate a kind of fate, as in dice games. There are systems using numbers — among them gambling, numerology, and astrology — that argue for a determinism by numbers. The human desire for patterns runs deep. The numbers won’t argue whether there is truth there or not.

As Domal ends Confessions by Numbers, “By telling these stories, numbers help us remember…that there is always strength in numbers.”

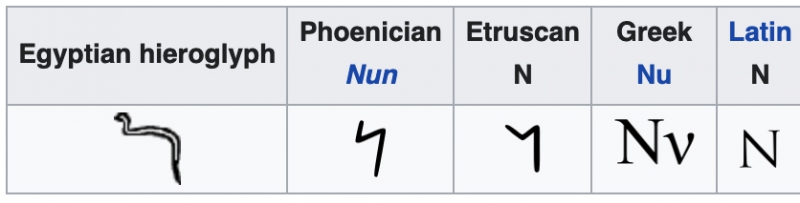

This is an Abecedarian Amble, and so what about that letter N? Its earliest root appears to be the Egyptian glyph for snake, a squiggle, which some call a wave. Later variations, evolving through Phoenician to Greek, end in the letter “nun” meaning fish. And our N results.

Image from Wikipedia.

Cope Cumpston is resident book designer, typographer, and community enthusiast. The archive for Abecedarian Amble lives here.