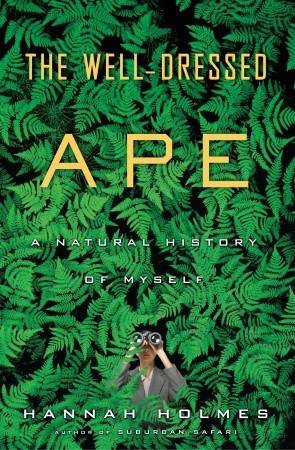

Joanne Manaster is an online course developer and lecturer for the School of Integrative Biology at the University of Illinois. She writes a blog for Scientific American and is a self described “public outreach enthusiast” who speaks and writes about science in general in a variety of media. On her own website, Joanne Loves Science, among other things, she posts video reviews of popular science books she likes. One such book is The Well-Dressed Ape – a Natural History of Myself, by Hannah Holmes.

In The Well-Dressed Ape, the author compares human anatomy and physiology to that of other animals, going into a number of related topics along the way. It’s a fascinating book. I met with Joanne Manaster recently and had a conversation with her about it.

Where did humans get the short end of the stick?

The author of The Well-Dressed Ape mentions that humans can distinguish around seven million colors — more than many mammals. So, our species came out ahead there. I asked Manaster if she could think of any ways physiologically that humans came out behind. She responded:

Before I answer that, there’s a really great book out called The Vision Revolution, by Mark Changizi. He talks about how the accepted view of why we have such good color vision is we can see different fruit and animals in the forest – stuff like that. But his theory is that having color vision helps us kind of mind read each other. By having color vision, I can see your skin color change – even if it’s just a little bit. If I’m sensitive to that, then I can tell if you’re ill or if you’re embarrassed. I can see the subtlety. So his postulate is that having color vision helps us in human interactions. So then the question becomes what came first – did we become more social and that improved our eyesight or did color differentiation help us become more social?

But what did humans get the short end of the stick on? I think it’s good that we can’t smell everything that a dog can [Laughs].

Manaster went on to talk about how the human body works well for us in many ways, but often at a price:

Our bodies are just a mass of trade-offs. If we fell off a skateboard, we are most likely to break these bones [gestures to bones in forearm]. And that’s because these bones are very thin. So why didn’t we evolve with thicker bones? Well, it’s because of the trade-off of being able to do this [rotates forearm back and forth] — a lot of animals can’t do that. Another book that looks at things in this vein — human health versus animal health — is Zoobiquity.

But there are certain things that are not advantageous. For example, our sort of over-expressions like fever. We have fever and that can be good because it speeds up certain actions in the body, but it can also kill us. So that’s bad. I don’t know how many other animals die of fever.

Another trade-off for humans is childbirth. Other animals have a difficult time passing a baby through the birth canal, but with humans it’s especially bad because the head is so large. So having an advanced brain can kill the mother. And that’s why humans need so much care as infants, because if the head were allowed to develop much more the baby would never get out. If we had some sort of zipper system, that would be great.

Basic Drives

In The Well-Dressed Ape, Holmes talks about how — in humans and in other animals — basic instinctive drives remain, even when the original reason for them are gone. She uses the example of how humans today often want to have a residence on the highest ground possible, whether it’s on the highest hill in town or in the penthouse suite. For our hunting and gathering ancestors, this made sense — high places were the best places to spot prey and also to watch for predators. These days, though, most of us can shop for food at Safeway and don’t have to worry about getting killed by saber-toothed tigers. Holmes also points out that house cats still hunt mice relentlessly, even when they’re getting plenty of cat food.

In The Well-Dressed Ape, Holmes talks about how — in humans and in other animals — basic instinctive drives remain, even when the original reason for them are gone. She uses the example of how humans today often want to have a residence on the highest ground possible, whether it’s on the highest hill in town or in the penthouse suite. For our hunting and gathering ancestors, this made sense — high places were the best places to spot prey and also to watch for predators. These days, though, most of us can shop for food at Safeway and don’t have to worry about getting killed by saber-toothed tigers. Holmes also points out that house cats still hunt mice relentlessly, even when they’re getting plenty of cat food.

I asked Manaster if these basic drives would ever disappear entirely. She answered:

Well, of course evolution works very slowly. Another question is how hard-wired these things are in our genes — what makes a cat go after a mouse. I don’t know the whole genetic picture and I don’t think anyone does yet — how much of that is really in there and what it would take to delete that genetic component.

Manaster talked about how our bodies still crave rich, fatty foods — even though eating them leads to obesity and other health issues — because in the past, during lean times, that was the best way for humans to put on some fat reserves to get by.

There are people who have lean times still, unfortunately, and until all of that is completely eradicated, I don’t know if all of us would move in a different direction. Let’s say a mother was suffering from malnutrition for whatever reason, and you’re that baby inside. You’re going to be saying, ‘Oh, things are lean,’ and you’re going to grow up to be extra good at storing things. You’re going to be more likely to have obesity issues when you grow up. There have been some really good studies on this. It’s called epigenetics — beyond genetics — where the environment is actually acting on the genes so that certain genes are sort of turned on and off for better or worse. So when you encounter some kind of banquet or plentiful food, you’re going to eat it and hold on to it because of the deprivation you encountered early on.

Are we understanding other animals more or less?

In The Well-Dressed Ape, Holmes discusses the difference between dogs, who have developed side by side with humans, and wolves who have not. Dogs have learned how to read humans, and can be trained to do things like be guide animals, whereas wolves can’t.

I asked Manaster if humans are understanding other animals more or less as we grow more distant from them, yet at the same time learn more about them scientifically. A middle-class human living in a city today might enjoy watching the squirrels play in the park, but doesn’t have to really stalk and understand animals the way his hunting and gathering ancestors did who depended on them directly for food. At the same time, with advances in biology, genetics, and so on, humans today have a far superior scientific understanding of other animals than our ancestors. So are we understanding animals more or less? She said:

You are going to have people who will say, we have removed ourselves so much from nature and following the seasons and things like that, but that’s kind of on an emotional level. I think we’re relating to nature in a different way by analyzing it so much and there are people who are critics of that. I think it’s nice to have the whole picture. I feel like I can maintain my relationship with nature and at the same time say, ‘This is me being a biologist.’

Most biologists, I think, are just drawn to nature to start with. Even if they’re molecular biologists in the lab. People who are biological scientists now probably had some kind of analogous role in primitive societies — maybe as shamans or some role like that. If you look at the biologists on campus today, there’s usually some kind of casualness or naturalness if you will — the Birkenstock thing. There’s some kind of drive in most biologists to be connected with nature.

We’re understanding more and more — although there are limitations to how far you can compare a squirrel to a human or a wolf to a human.

A new kind of human?

Hannah Holmes writes in The Well-Dressed Ape how humans — along with animals like tigers and the great white shark – are apex predators, at the top of our food chain. But we weren’t originally — we got that way through our ability to develop and use tools.

Now that animals that prey on humans — crocodiles, big cats, polar bears, etc. — are not the threat to us that they once were, we’ve turned our weapon and tool making abilities against each other.

I asked Manaster if the stresses humans put on one another — for example, subjecting humans on the ground to the stress of continually watching out for unmanned drones in the air above — might cause some humans to adapt and evolve in new directions. She responded:

That’s very possible. This is all speculation, but a subset of people could advance in one area, say hearing or the ability to do something else. Maybe sense if something is above.

When we look at human evolution, we have the Neanderthal and others; we have different subsets of humans, but one became dominant — Homo sapiens. There’s no reason another subset couldn’t separate off now. It could happen, and there’s been a lot of speculation on that.

It would take a lot of time. People a couple of million years from now may look back and say, ‘Oh, yeah, homo sapiens, they were so lacking in blah, blah.’ And they would even look back and know that it was a particular stressor.

Because that’s what we’re doing. We’re speculating that it’s about the savannah. That early humans were on the savannah, this open area without trees, and that’s why we got up and walked. And we were able to run, which led to getting hot and needing a way to cool down. So we started to drop off the hair. So there will be people speculating about us if we branch off — and we may very well.

Why are humans compassionate?

Hannah Holmes makes the point in The Well-Dressed Ape that humans have the greatest potential to harm the environment (other animals probably aren’t going to put a hole in the ozone layer), but at the same time have the greatest capacity to preserve and protect — even our predators. Holmes mentions how in the American west big cats are an actual threat to some humans in areas, but still people are passionate about protecting them. Only the human animal is like this. Owls don’t appear to have any moral scruples about killing mice.

I asked Manaster why she thought we were like that, why we have an urge to preserve and protect — is it just from self-interest somehow, or something more? She said:

Well, you can be altruistic to gain respect. You’re seen as being better in the eyes of other people. So maybe that’s part of it. I would run out in the street to save a child who had run in front of a car, but I could die and then my children are left without a mom. But we have that drive to kind of be a hero. We do that for people so maybe we do it for animals as well. It must have something to do with altruism. Something innate that wants us to be connected. Where we evolved to where we felt we should have to do that, versus an owl who doesn’t care about the mice it kills.

Feature image taken from Ms. Manaster’s Twitter page.