Drug policy has been receiving intensified attention at both the national and state levels as a result of two developments. The first is the increased presence of fentanyl worsening the opiate crisis. It is even taking hold in our community. As reported in the News-Gazette, of the 69 deaths resulting from drug overdose in Champaign County last year, fentanyl was involved in 41. The second is the White House’s declared support for funding harm reduction programs. It is a good time to reexamine our beliefs and our laws concerning drug use and decide what is fear-driven and what is sensible.

I reached out to Joe Trotter, the Harm Reduction Program Coordinator at the Champaign-Urbana Public Health District, to see what our local harm reduction program does and his thoughts on how drug use should be addressed. Trotter has been with CUPHD since 2006, and he is a recipient of the “Beth Wehrman Award – Takin’ It To The Streets.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Smile Politely: What are some of the things that the harm reduction program does?

Joe Trotter: Our program’s goal is to provide health services for people that inject drugs while they’re still actively using to help them to reduce the harm to themselves and to others nearby them. An individual can often have abscesses, scar tissue, or wounds on their arms that result in infections. And then, as the needle is often shared, there’s a big risk for transmitting HIV and Hepatitis C.

SP: Can you give examples of services you provide?

Trotter: Probably the biggest example is a traditional syringe exchange. That’s the term that most people are familiar with. But the term that we use is syringe services programming, meaning we do more than just hand people needles.

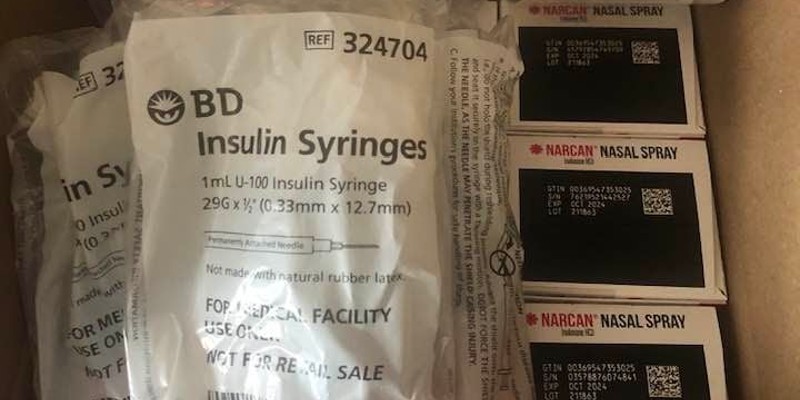

Primarily, we provide clean needles to the drug-using population. We want people to use a clean needle every time, while they’re still using. Using a clean, new needle every time greatly reduces the harm that they can do to themselves. And then we want that needle to be disposed of properly and not shared with anybody else.

There’s a lot of other drug-using equipment that we hand out like band aids, tourniquets, and alcohol pads. We also provide harm reduction counseling. We talk to our clients about ways that they can help protect themselves and help protect others that they might be using with. We provide clients with additional services like HIV, Hepatitis C, and STI testing with Family Planning Services. We also do HIV prevention and HIV care.

And now, we offer fentanyl test strips. It’s a tiny little test strip similar to — I mean, it kind of looks like a pregnancy test. It gets dipped into water mixed with a particular drug that’s being used, and it either shows that fentanyl present or not. It’s not going to show the amount of fentanyl present, just if fentanyl present or not.

Fentanyl is a really strong drug that’s often added to drugs that are being used. It’s light and easy to transport and conceal, so drug preparers and dealers have found that it’s an easy, cheap way to make a drug stronger, which means it sells better. But people using those drugs might not know how much has been added or how strong it is. Fentanyl testing gives someone that’s using street drugs like heroin or methamphetamines the awareness to know, “Okay, this contains some amount of fentanyl. I need to be more careful because fentanyl is so potent.”

Fentanyl use has a high risk of overdose. Any kind of opiate runs the risk of an opiate overdose, but, when combined with fentanyl, it can be more dangerous. We also offer Narcan or Naloxone, which is a medication that’s used to stop an opiate overdose that’s actively happening. So, if someone’s overdosing, you administer this drug to them, and that stops the overdose from continuing.

The goal is for you to stay safe for as long as you’re actively using, however long that is. If you’re ready to quit in two weeks, cool. If you’re ready to quit in two months, that’s cool. If you’re ready to quit in two years, that’s cool. The client decides when they’re ready for that.

This is all part of our comprehensive clinic here at Public Health. We’ve been doing our Harm Reduction Program for about 15 years now, so we’re pretty well established in the drug-using community to offer them the services that they need.

SP: If someone wanted to access these services, how would they go about doing that?

Trotter: They’re all integrated into the Division of Teen and Adult Services at the Champaign-Urbana Public Health office. Anyone can come in at any time during our operating hours: Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. They can walk in, go back to Teen and Adult Services, and either ask for me specifically or just say “I’m here for clean needles” and they’ll get routed to the right staff.

Everyone meets with a counselor individually in a private office, and that interaction is anonymous. We don’t collect name, address, phone number, or anything like that.

When they come in, they are considered a participant of our program, and, because our program is registered with the state, we are able to offer limited legal protection. Participants of our program have some legal exemptions for carrying more than 100 needles, carrying what the law terms paraphernalia, and getting arrested for drug residue charges. Let’s say someone has a dirty needle and they’re trying to dispose of it. They can get arrested for drug possession. But, if they’re part of our program, the law is able to offer them some protections against what would be a felony charge.

We have a lockbox at the back of our building that allows our clients to get services or supplies at times that we might not be open.

We do a few referrals to drug treatment, but that’s not our primary goal. We are client-centered, which means we talk about what the client wants to talk about at that particular moment. If the client says, “Hey, I need to talk about my arms. I’m worried about scar tissue or abscesses,” then we’re going to talk about that. Or, “I have concerns about housing, I need to try and find alternate housing. Can you refer me to help with that?” But if a client does say they’re ready for drug treatment, then we’ll talk to them about preparing for that and give referrals to local resources.

SP: Are there studies or statistics that you can point to about the efficacy of programs like syringe exchange?

Trotter: The cool thing about a program like ours is that it’s been studied for a really long time. Opponents to syringe exchange think that we’re enabling them to use drugs. We’re not. We’re just keeping them safe for as long as they’re using drugs.

It’s a different kind of mentality. The way that I think about it is society asks, “Are you using drugs, or are you not?” and there’s not really space for them in between that. Syringe exchange is really meant to be in between, like, “I’m not ready to stop using drugs, but I also want to stay safe. I don’t want to catch a disease or pass a disease to someone else nearby me.” We’re really meant to be a kind of in-between service for a lot of folks.

It’s also just to have someone who isn’t going to pass on a judgmental “don’t use drugs” message that we know doesn’t really work. Previous administrations have been saying that for years, and the data has never really supported it. But the data does actually support harm reduction approaches. People do get better. People access drug treatment and have better outcomes when they’ve been involved in a syringe exchange, simply because they’re getting positive health messages from someone in a non-judgmental setting.

I like to think that we’re drug neutral, that we’re not drug negative. We’re not saying, “Don’t ever use drugs!” and we’re also not saying, “Use all the drugs!” We’re saying, “If you’re going to use the drugs, here are the ways to do it safely.” In the same way that the Department of Transportation doesn’t tell people, “Don’t drive because driving causes car accidents.” They give them seatbelts. Harm reduction is that kind of seatbelt in drug use.

SP: Let’s say that I know or suspect someone is using drugs. Do you have any advice on how I should approach that situation or offer help?

Trotter: If you have someone close to you and you’re concerned about drug use, I think it’s perfectly safe to say, “Hey, you know, if you are using a drug, it is helpful for me to know it.” Particularly when we’re talking about street drugs, because street drugs often have alterants added to them which can make them more potent or often be a drug that people aren’t used to taking.

If you approach it like, “Hey, if you’re using a drug, it’s okay to talk to me about it. I’ll try and be as judgment free as I can. I just want to keep you safe.” And then if you can have an open conversation about them, then you can talk about, “If something does go bad in your drug use, what are ways that I can support you?”

If someone experiences an overdose, then it’s good to have talked to them about, “If something does happen, or you fall unconscious, what would you like me to do? Are you comfortable with me doing rescue breathing or CPR with you? Where do we keep the Narcan in the house? Is there someplace that I can take you if you’re overdosing? Like, is there a particular emergency center that you’re more comfortable going to?”

People often use drugs alone because of stigma, because of fear, because of fear of backlash. So, if we can say, “While I don’t like the idea of you using this drug, I also don’t want you to die. So, tell me when you’re using that drug, so I am aware, so I can help you stay safe, so I can help keep an eye on you.” That is not enabling. That is care. That is love.

There’s so much bad stigma and bad energy around illicit drug use that could easily be repaired simply by saying, “Hey, I care about you even while you’re still using. I love you even when you are still using, and I want to keep you safe. I want to keep you healthy, and you still deserve safety and health and care while you’re using drugs.”

But our society is not really written that way. Our society has written, “If you’re drug-using, then we have to cut you off. We have to ignore you have and do all these things.” While I agree that people need to have a healthy boundary with people around them who are using drugs, it’s also important to say, “Hey, I just want to try and keep you safe and keep you cared for.”

There’s a program called Never Use Alone. It’s a national program that allows someone that is using a drug to call in and have someone that can record where they are. So that way, if they are using the drug, and they do fall unconscious, emergency services can be called that on their behalf. For example, you can’t stop yourself from overdosing. Someone has to witness your overdose, and they have to do something about it.

It’s really important that we start to think about drug use differently. Particularly because opiates and fentanyl are just so prevalent right now.

SP: What would you say is the biggest barrier to implementing these programs in the Champaign-Urbana area?

Trotter: Stigma is probably the core of it. But one really great thing about our Public Health is that we have a board and an executive director that are all progressively minded. They follow the data that firmly and strongly supports the concept of syringe exchange and safe consumption practices. In a lot of other areas, syringe exchanges and harm reduction programs are often looked down upon because people don’t realize the effectiveness that they have on a population.

And it doesn’t take much to as far funding to make a harm reduction program successful. We operated for years without any kind of funding. And operated well. Funding is always helpful, but it isn’t the major barrier that people think it is.

I think it’s always important for us not to forget that that our clients do come first, regardless of funding or popular opinion, or feedback or anything like that.

SP: Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you wanted to bring up?

Trotter: I should talk more about our Narcan program. We give Narcan to folks that are using drugs, and we also give Narcan to anybody in the community who wants it. There’s now a standing order in Illinois that falls under Good Samaritan rules allowing anybody to carry and administer Narcan. That also means that you don’t have to get training. You don’t have to have a special permit or license or anything to carry it.

We have a 10-county region of Illinois that we supply Narcan to. We’re targeting any place that’s open to the public: restaurants, bars, gas stations, liquor stores, smoke shops, or churches. We can supply any agency or community group that wants Narcan, and we can supply them with group training that takes a little less than an hour.

It’s completely free of charge. We get it from the state for free, and we pass it along to everybody else for free. And the goal being that we need to cast a wide net for overdoses. Any place that’s open to the public could have some risk of having this emergency happened nearby them. There is no risk of giving Narcan to someone that’s unconscious. If there are opiates in their system, it’ll stop the opiates. If there aren’t opiates in their system, nothing happens. It’s safe to give to someone regardless of their medical condition.

And we’ve had reports of reversals, you know, from this from this outreach program, so we know that it’s working.