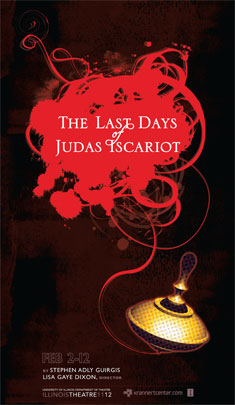

When I sat down in the Studio Theatre and looked around, I said aloud that Stephen Adly Guirgis’ The Last Days of Judas Iscariot wouldn’t “be at all biblical.” The stage was as cluttered as any I’d seen. It was a mess. Or — depending on how you look at it — it was a room that any scholar would be proud of. Desks, shelves, and tables were overflowing with books and papers. Books were piled in stacks of varying height all over the stage, in front of chairs, tables, and shelves. And there was a balcony overlooking the stage that also contained a desk and chair covered with more books and papers. As I said: a chaotic mess.

When I sat down in the Studio Theatre and looked around, I said aloud that Stephen Adly Guirgis’ The Last Days of Judas Iscariot wouldn’t “be at all biblical.” The stage was as cluttered as any I’d seen. It was a mess. Or — depending on how you look at it — it was a room that any scholar would be proud of. Desks, shelves, and tables were overflowing with books and papers. Books were piled in stacks of varying height all over the stage, in front of chairs, tables, and shelves. And there was a balcony overlooking the stage that also contained a desk and chair covered with more books and papers. As I said: a chaotic mess.

As the actors entered the stage — ghostly figures in the dark, slowly walking into the room — the wind whistled and howled. And then — to every book lover’s horror — they … they didn’t step around the piles of books. They stepped on and sat on them instead, as they continued to do throughout the play. I had to just get over it. And I got over it because it became clear that these characters are inside the books that they’re stepping on, sitting on, and sometimes rolling around upon. They are the history, the poetry, the drama, and the romance within these books, so it makes sense that they don’t feel reverent toward them.

Indeed, there is nothing reverent about The Last Days of Judas Iscariot. Nothing is sacred: beloved saints; beatified nuns; our own beliefs, values, and sensibilities. All are challenged; all are questioned and found lacking.

The cluttered room is a courtroom in Hope, Purgatory. There is, in fact, jurisprudence in the afterlife. Fabiana, a lawyer serving out her time, has taken on Judas Iscariot’s case. She has a signed writ from both Saint Peter and God that Judas’ sentence of eternity in Hell is too harsh. Yusef is the prosecuting attorney. Littlefield is the judge who reluctantly takes the case. Gloria, an Angel who resides over Hope, and two humans (one dead and one dying) serve on the jury. Saints Thomas, Peter, and Matthew are simply there to hang out, watch the proceedings, and provide occasional commentary.

And, of course, Judas is there. And we wonder whether he wants to be defended at all. And I soon came to realize that I was completely wrong about this play not being biblical. The genius of Last Days is that it was written by someone clearly immersed in theology. But those familiar only with the Bible will not have an advantage. Guirgis references the Church Fathers, the Gnostic Gospels, and — I believe — the Dead Sea Scrolls. This play will send you to the library or your computer or — if you’re lucky — your own bookshelves to look up (or re-familiarize yourself with) various names and references such Jerome, Augustine, the Sanhedrin, Josephus, and Saint Matthias (more on this later).

We meet many familiar characters, both ancient and contemporary: Mary Magdalene, Pontius Pilate, Satan, Mother Teresa, and Sigmund Freud. But for me, some of the most compelling personalities are the lesser-known or fictional ones. Jessica Dean Turner is simply divine as Saint Monica. Whether she’s dancing for the audience’s (and her own) pleasure, yelling her head off about societal injustice, or softly contemplating the state of a man’s soul, Turner is convincing and interesting and real. She manages to combine warmth, irreverence, and sexual energy all into one glorious package. I couldn’t take my eyes off of her when she was on stage. This is the second time that I’ve seen Turner display her impressive range. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream — It’s a Bacchenal, she effortlessly played two disparate characters, and here she shows two organic facets of the same complex person, and does so seamlessly.

We meet many familiar characters, both ancient and contemporary: Mary Magdalene, Pontius Pilate, Satan, Mother Teresa, and Sigmund Freud. But for me, some of the most compelling personalities are the lesser-known or fictional ones. Jessica Dean Turner is simply divine as Saint Monica. Whether she’s dancing for the audience’s (and her own) pleasure, yelling her head off about societal injustice, or softly contemplating the state of a man’s soul, Turner is convincing and interesting and real. She manages to combine warmth, irreverence, and sexual energy all into one glorious package. I couldn’t take my eyes off of her when she was on stage. This is the second time that I’ve seen Turner display her impressive range. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream — It’s a Bacchenal, she effortlessly played two disparate characters, and here she shows two organic facets of the same complex person, and does so seamlessly.

Mike DiGirolamo as Simon the Zealot is brilliant. His contempt for authority reminded me of every activist I’ve ever been involved with. And his naïve and genuine admiration for Jesus and Judas is touching. An inspired performance.

Judas’ mother testifies that her son was a generous and loving boy, and a scene is enacted in which Judas gives a cherished toy away to another, poorer boy who has none. The boy’s name is Matthias: the name of the man chosen by the remaining apostles to replace Judas after his death. Last Days is replete with these kinds of symbols, metaphors, and references. From its beginning, when Monica refers to Judas as “the leastest creature” she’s ever seen to its ending when Gloria breathes new life onto Earth, we’re immersed in allegory. This play is not an escape from reality; it is our own “gospel,” our everyday reality. Nor is this a play that you can watch passively. It’s a thinking man’s story, more philosophy than fiction. When both Satan and Caiaphas can — with conviction and without irony — challenge society’s conception of justice, when Jesus is the least helpful and potent of the bunch, you know you’re about to be awestruck.

The play’s cast mostly includes seasoned upperclassman and MFAs. I’m beginning to think that it’s impossible to perform badly under Lisa Gaye Dixon’s direction. Surely, a play with an ensemble this large (19 cast members) would have a few problems? But that’s not the case. Everyone is enjoyable, professional, and realistic, and I wish that space and time allowed me to spotlight all of them.

I’ve discussed Neala Barron’s talent before, and as the defense attorney in Last Days she is heartbreaking. When we first meet Fabiana, she seems strong and capable. She’s going to kick butt. Somehow, she’s going to pull off a miracle and overturn Judas Iscariot’s conviction. We think this because Barron’s Fabiana owns that courtroom. But as the trial progresses, it becomes glaringly clear that Judas isn’t whom Fabiana is defending at all. Barron depicts all of this without explicitly saying any of it.

I’ve discussed Neala Barron’s talent before, and as the defense attorney in Last Days she is heartbreaking. When we first meet Fabiana, she seems strong and capable. She’s going to kick butt. Somehow, she’s going to pull off a miracle and overturn Judas Iscariot’s conviction. We think this because Barron’s Fabiana owns that courtroom. But as the trial progresses, it becomes glaringly clear that Judas isn’t whom Fabiana is defending at all. Barron depicts all of this without explicitly saying any of it.

No review of this play should neglect Sam Ashdown, whom I’ve enjoyed in many plays at the Krannert Center, most especially in Killer Joe. Ashdown portrays three different characters in Last Days: Pontius Pilate, Sigmund Freud, and sloppy drunk Uncle Pino. And he manages to disappear into all three. As Uncle Pino, he is only on stage for a few seconds, but I didn’t even know that he’d played that role until I saw it in the program. Moreover, it’s interesting to me that Dixon decided that the same person would play Pilate and Freud. In earlier productions of this play, these roles weren’t played by the same actor, so this decision seems to be solely Dixon’s inspiration. And in Ashdown, she chose well. His ability to play both roles convincingly, becoming two starkly different, but crucial, witnesses in Judas’ trial, affirms an impressive talent.

No review of this play should neglect Sam Ashdown, whom I’ve enjoyed in many plays at the Krannert Center, most especially in Killer Joe. Ashdown portrays three different characters in Last Days: Pontius Pilate, Sigmund Freud, and sloppy drunk Uncle Pino. And he manages to disappear into all three. As Uncle Pino, he is only on stage for a few seconds, but I didn’t even know that he’d played that role until I saw it in the program. Moreover, it’s interesting to me that Dixon decided that the same person would play Pilate and Freud. In earlier productions of this play, these roles weren’t played by the same actor, so this decision seems to be solely Dixon’s inspiration. And in Ashdown, she chose well. His ability to play both roles convincingly, becoming two starkly different, but crucial, witnesses in Judas’ trial, affirms an impressive talent.

The imperfections within Last Days lay not with the cast or direction, but rather with the play itself. As part of her defense, Fabiana shows Judas approaching Pilate, begging him to release Jesus. She and Pilate cite the Book of Matthew for this incident, but this is incorrect. Nowhere in the Bible does Judas address Pilate. In Matthew 27:3, Judas returns the 30 pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders, saying that he betrayed an innocent man. So that confused and distracted me throughout that entire scene. Even if it is an artistic liberty, the point seems evasive.

Additionally, the play lasts about ten minutes too long. The final scene, while well-acted, seems — with respect to Guirgis — superfluous.

But these small issues aside, The Last Days of Judas Iscariot is a compelling, engrossing play. I highly recommend it. But bring your thick skin.

Strong adult content and language

Future shows:

Wednesday–Saturday, Feb. 8–11, 7:30 p.m.

Sunday, Feb. 12, 3:00 p.m.

Studio Theater

Program (pdf)

Dear Krannert Center: when your own actors have to improvise their dialogue to ask audience members to turn off their cell phones, you’ve got a problem. Can you please be a little more effective concerning your stated “rules”?