The Keystone Kops, Charlie Chaplin, the Bathing Beauties-these American icons helped define early twentieth-century American popular culture. But where did they come from? And why did they appear when they did? A new study helps us understand the forces that converged to give us the pleasure of these spectacles.

The Keystone Kops, Charlie Chaplin, the Bathing Beauties-these American icons helped define early twentieth-century American popular culture. But where did they come from? And why did they appear when they did? A new study helps us understand the forces that converged to give us the pleasure of these spectacles.

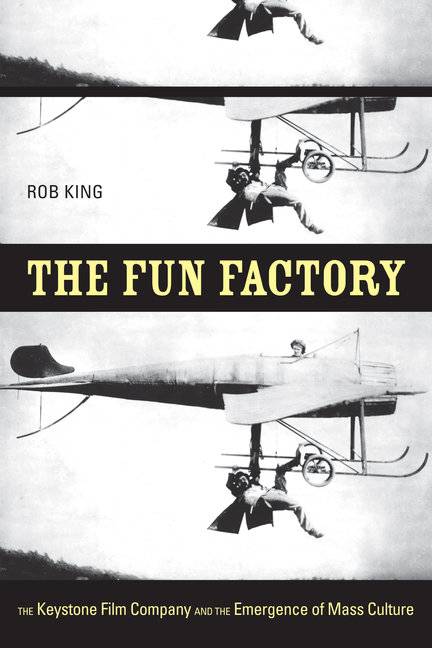

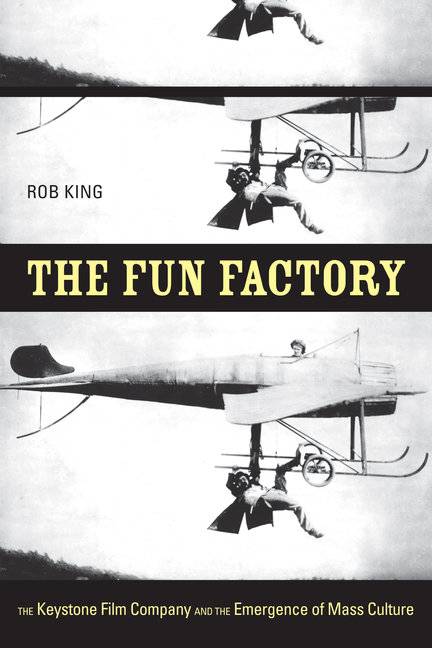

That a reader will learn about much more than the Keystone Film Company (Keystone) by reading The Fun Factory: The Keystone Film Company and the Emergence of Mass Culture, by Rob King, Assistant Professor of Cinema Studies and History at the University of Toronto-speaks to both the strengths of the author, and of the field of Cultural Studies. Moving from the specific to the general, and vice versa, King’s book argues that to study Keystone is to study the history of emerging mass culture at the beginning of the twentieth century in America.

King offers fascinating accounts of immigration, the rise of industrial production (at Henry Ford’s automobile plant, for example, the assembly line proved so organized that workers “never had to move from their posts”), and the emergence of the so-called New Woman. He explains that these trends gave rise to a new social order, whose tensions were relieved in part by laughter; hence the creation of the Keystone style.

King’s study focuses on the comic form of slapstick, primarily because this emerged as the benchmark of the Keystone style. He reviews definitions of slapstick such as narrative excess, and a fictional rupture typically contained by the plot-definitions that position it as different from the dominant forms of classical Hollywood cinema. Yet, while King agrees with this characterization, he notes its limitations, in that it freezes comedy “within the bounds of its own alterity.”

Because comedy is ultimately a series of social gestures, King argues, we must read various comic forms in their historical moment to truly understand their significance. To King, slapstick proved a comic form attuned to working-class values such as the send-up of workplace authority and social pretension.

That we learn (or review) a lot of American history does not mean King’s study de-emphasizes formal analysis. On the contrary, he advances his analyses frame by frame, editing technique by editing technique, King slowly builds up to a chapter devoted entirely to a formal analysis of “Tillie’s Punctured Romance” that closes Part I of his study. He argues that this full-length feature maintains its focus on subversive slapstick, despite pressures to devote energy to more respectable narrative forms. Indeed, a main point of King’s study is that those at Keystone admirably resisted attempts to conform its productions to dominant values.

An academic study that is by definition too complex to be productively summarized, The Fun Factory nevertheless proves immensely readable, as it offers analyses of, among other things, Keystone’s relentless burlesque of D.W. Griffith’s melodramas, and the contrast between the ethnic clownings of Ford Sterling and Charles Chaplin. King explores Keystone’s vexed relationship to emergent highbrow film culture, noting that Keystone “reworked and adapted [genteel culture] for a cross-class audience,” and thus participated in a “process by which older middle-class values were redispersed within the new commercial mass culture, eventually paving the way for new categories like ‘middlebrow.'”

In his discussion of Keystone’s engagement with an increasingly automated society, King asserts that Keystone understood the American public’s attraction to technical process-even as that public was disturbed by the consequences of technology. The comedy of these shorts derived from confusion caused by the mutual substitutability of machine and human.

The final chapter of The Fun Factory traces, and laments, the marginalization of subversive enactments of working-class femininity in Keystone productions over the span of just a few years. King focuses on the fascinating career of Mabel Normand, arguing that because her portrayal of a water nymph relied on a body both classical and grotesque, she demonstrated that pretty women could in fact be funny, a radical concept in that day.

Yet it was bodily restraint and order that then infused Keystone’s Bathing Beauties, who became, unfortunately to King’s way of thinking, exemplars of the new mass culture-and who thus helped to define women’s modernity in commercial terms, as the pursuit of physical perfection through the purchase and use of an endless array of beauty products.

Because King remains committed to positioning Keystone as an agent of resistance, however, he invokes Jurgen Habermas’s argument that consumer society transformed the public sphere from a place for public discourse to a place for the stimulation of commercial desire, to explain-and excuse-this evident conservative shift in Keystone productions.

Carefully argued and exhaustively researched, The Fun Factory reinforces-for the converted-a sense of what Cultural Studies can and should do. On the other hand, this fascinating social history (a good, good read) can help convince the skeptical or the uninitiated that seeking out books in this field can enjoyably deepen one’s understanding of the fascinating history of America.