Everyone knows the story. Constant re-imaginings, new casts and directors remain within an electric arc of each other: A mad scientist uses electricity to bring life back to a dead body. Neck bolts. Suit stolen from a mannequin in the Boy’s Department. Platform boots.

Everyone knows the story. Constant re-imaginings, new casts and directors remain within an electric arc of each other: A mad scientist uses electricity to bring life back to a dead body. Neck bolts. Suit stolen from a mannequin in the Boy’s Department. Platform boots.

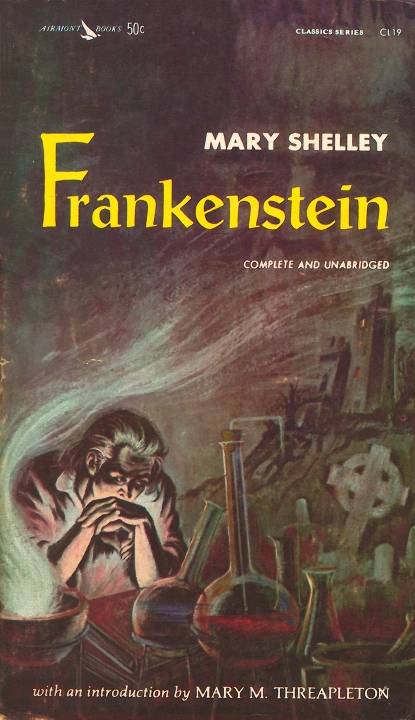

When eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley spun the original ghost story, it was nothing special, but her poet husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, encouraged her to develop it into a novel. He helped her revise the manuscript, suggested cuts and rewrites. Frankenstein was published anonymously in 1818. Despite a few positive reviews about the potential of the author, many critics of literature tore it apart, calling it “a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity.” It caught on with the unwashed populace, however.

Frankenstein starts at the beginning of a letter written by Robert Walton to his sister, Margaret. Walton is a sea captain aboard a ship called Archangel, bound for the frozen North at the top of the world next to the Snickers bars. The ship picks up a hitchhiker stranded on an ice floe. The exhausted young man asks which way the ship is headed and stays aboard for the trip. It is the passenger’s story that Walton now writes of to his sister.

Already this is hearsay. In fourth person, the letters describe the stranger as a man whose spirit had been broken by misery. Walton must have whispered ‘Open, sesame’ in the man’s ear while he recovered because he tells the captain about the whole sordid affair.

Victor Frankenstein lived a charmed life. He was born in Geneva, betrothed to a ward of his family—a cousin it turns out. Frankenstein harbored a secret desire to perform super science. Then it was referred to as natural philosophy, but described alchemists and the precursors of physicists, still looking for the Philosopher’s stone, ill humours and answers to other pressing questions about the back of the tortoise the world rested on.

Herr Frankenstein travels to Germany, to the University of Ingolstadt, to study gravity or the new dope, electricity. After some months of tutelage, he begins experimenting. Mary Shelley never delves too deeply into what Frankenstein does during these episodes. She keeps it vague. ‘Just file it under Science Stuff,’ she says, hurrying us along with stiff fingers pressed to the smalls of our backs.

My suspension of disbelief reached the breaking point when, after less than a year of diligent natural philosophic study, Victor Frankenstein has the ability to bring life back to dead tissue. He succeeds with animals then decides to try it with a man. Not a body robbed from the executioner’s pile or a fresh grave. No, the original Frankenstein’s monster was an embroidered amalgamation of dead tissue gathered over time from slaughterhouses and dissection rooms.

In real life, piecing together human body parts in one’s apartment for a few months without the benefit of refrigeration would release a stench strong enough to draw comment from passersby, but Shelley must not have taken this aspect of reality into account. She further refuses to tell us how Frankenstein brings the grotesque to life. She could have read a book on the human body or researched natural philosophy to make up something plausible. Nothing. No electrical transformers or lightning or lab coats and goggles. I felt bereft and cheated, and a bit disgusted with Mrs. Shelley.

When the hideous being opens its yellowing eyes, the consequences of Frankenstein’s actions dawn on him. He cringes in horror at the abominable monstrosity he’s created. In a fit of conscience, the dabbler runs from his rooms into the street. Frankenstein does not see or hear from the patchwork devil again for an entire year, not until the budding scientist arrives in Geneva for a family visit. The night before, his younger brother was found strangled in the woods; a female retainer stood accused of the crime. Frankenstein finds the spot where his brother was killed and sees the hulking form of his creation lurking there. He knows it is the monster that killed his little brother.

Shelley often interrupts the narrative to explain how the creature comes by pertinent information, no matter how far-fetched the circumstances. The creature tells Frankenstein about its life thus far: It knows how to read and speak French because it spent a year spying on a family through a hole in the wall of their cabin. It knows who its creator is and where he lives because it found a convenient journal in its clothes. Somehow the unschooled freak show found its way from Ingolstadt to Geneva to seek revenge on its creator for a life it did not ask for.

The monster demands that Frankenstein make a woman for him, a companion. It promises to disappear with this new partner into the depths of the Amazon, never to bother mankind again. If Frankenstein refused, the monster swore that he would make the young man’s life miserable until the end of his days. Frankenstein agrees eventually, but he must travel to England in order to consult some men of learning that have certain information that would help him in his grisly work. Shelley does not bother to suggest the nature of this information. Feeling further cheated, I kept reading, suspecting that it wasn’t worth it.

After two more deaths in the family because of his conscience, Frankenstein goes mad for a time. It happens at least once more during his story. Rather than adding anything to the plot or character development, these intervals of mental fragility seem to be easy ways to kill time. The hero can’t go right after the monster when it kills his best friend, but there’s nothing going on in town more important than a revenge killing.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a dismal execution of a novel. Its plot holes, logic failures, and unbelievable reactions make this book more of a tragedy than the parable against hubris it contains. As it stands, three versions since its 1818 publication, Frankenstein could use still more revision and maybe a motivation. Ironically, the book is well-written. The language is rich and lyrical, if a trifle Shakespearean when the monster gets threatening:

“I will glut the maw of death, until it be satiated with the blood of your remaining friends.”

Instead of reading Shelley’s freshman horror, Frankenstein, watch one of the movies loosely-based on the novel: the 1931 version, Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman, any of them. When Dr. Frankenstein shouts, “It’s alive! It’s alive!” thank Mary Shelley for the influence. Try reading her short stories. A collection of these, Transformation, is decent.

Rating: 1 of 5