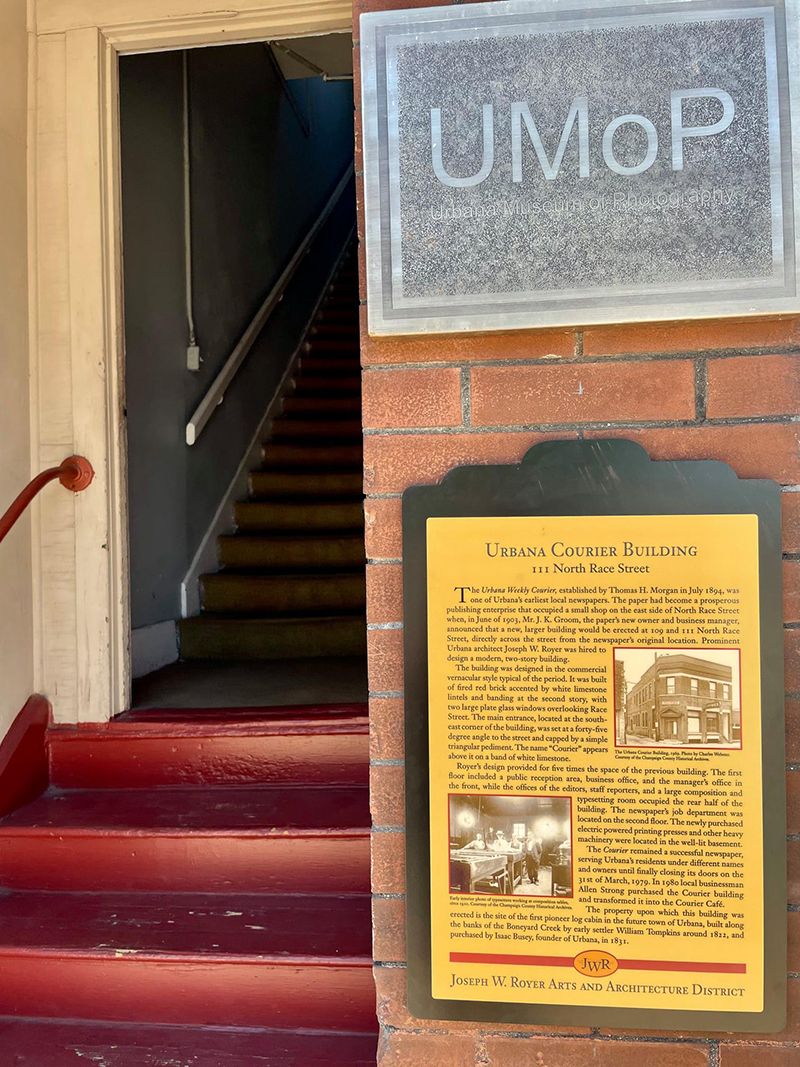

An interview with the humans behind Urbana Museum of Photography (UMoP) requires an in-person visit and face-to-face conversation. To Zoom, chat, or e-mail with those called to carry on the tradition of analog photography would miss the point entirely. So this week I made my way to UMoP to meet founder and owner Lyosha Svinarski, and curator Anna Longworth. Here’s what happened.

UMoP now resides within the hallowed halls that were once home to the The Urbana Courier newspaper. The Courier’s darkroom was shuttered from 1979 to 2017, when Svinarski brought it back to life. This resurrection forever binds UMoP to local photographic history. And while you may find a few examples of historic Urbana photographs on your way up to 113B Race Street, they do not define the space or its purpose.

Photo from the UMOP Facebook page.

While it may appear compact, UMoP offers experiences and opportunities that extend far beyond its square footage. The walls of the gallery space invite you to enjoy the photographs that were originally curated for Boneyard Arts Festival. Cameras from years gone by beckon to you, luring you back into the history of photography. At its center sits a round table and three chairs, and for my purposes, and I suspect for those of members of the UMoP community, this is where the magic truly begins.

As I sat with Svinarski and Longworth, there were three iPhones on the table. One was face down, one was open to the list of pre-interview questions I had emailed ahead, and one, mine, was functioning as a recording device. For the next hour or so, there was no such thing as a smartphone camera. I had entered an analog space. And though the recording of our interview was an attempt to capture the experience, mostly for fact-checking purposes, I quickly relaxed into the rich conversation that followed. We discussed UMoP’s origin story, photography’s evolving history and role, and, inevitably, the digital v. film debate.

Photo from the UMOP Facebook page.

What developed (pun intended) over the course of my visit felt more like the type of passionate exchange I remember having with my fellow arts and philosophy students at NYU than the volley back and forth of a typical interview. And I was more than fine with that. Not only did learn more about two photographers and what they do, but I learned why they do it. And perhaps, most significantly, I shared a deep dive into the way film photographers think, and how they view the world and their place in it.

Photo provided by UMoP.

Svinarski is an avid reader. He spoke often of Susan Sontag’s On Photography, citing both her both discussion of the history of American photography in terms of the “idealistic notions” of Walt Whitman, all the way to the “increasingly cynical aesthetic notions of the 1970s, particularly in relation to Arbus and Warhol.” When I asked “where are we now?” Svinarski’s answer, put simply is “nowhere.” We are without a major movement. We are waiting to see what happens next.” And in the meantime, analog evangelists like Svinarski and Longworth, continue to navigate the predominance of digital photography and social media.

Svinarski rightly asserts that you can’t talk about photography without talking about technology. In our consumer-driven, keeping up with the Jones’-like obsession with the latest and greatest, digital technology continues to deliver high, and, even lower-end, cameras that require less and less of the humans who wield them. At the risk of heading down the Marshal McLuhan rabbit hole, it is clear that the medium, or, rather the technological tool, is still very much the message. To paraphrase Svinarski, the more expensive the digital camera, the more trust we place in it. And the more power we give it. More and more we allow it rather than us to make the choices. And as cameraphones compete with digital cameras, the convenience of carrying one portable device often wins out. Annd with this shift comes the movement towards content creation, and away from purposeful, and, artfuly expressive photographs.

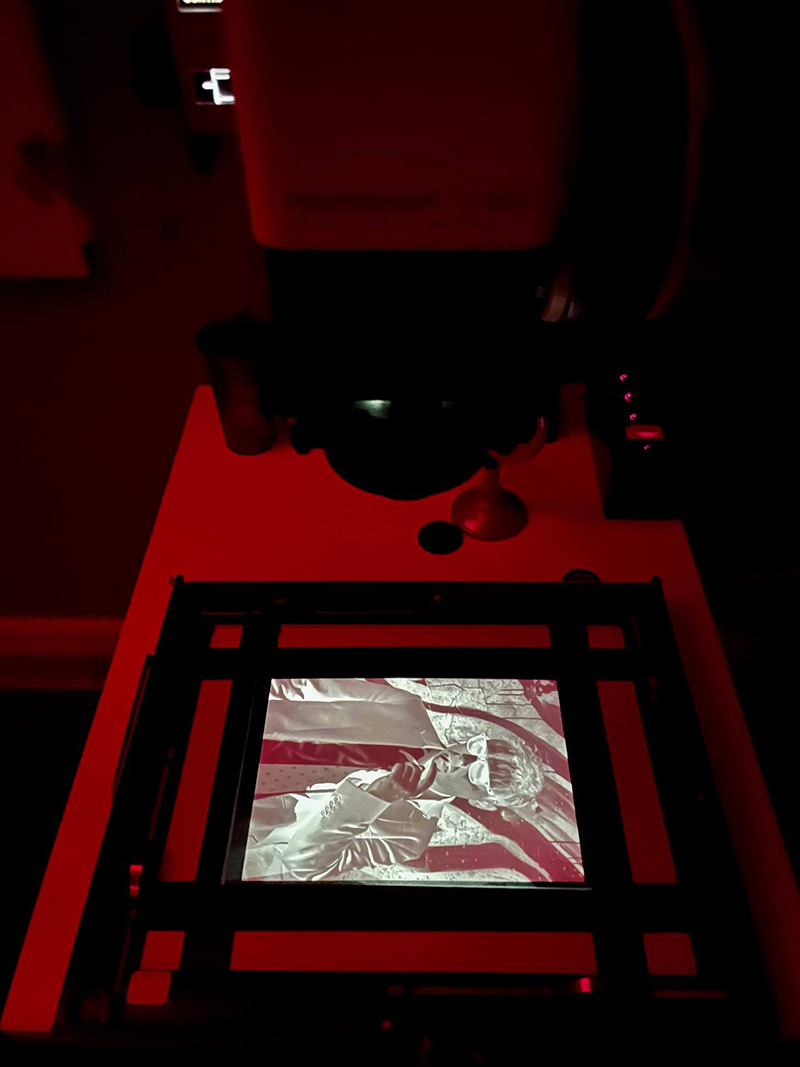

It is also true that one can’t talk about photography without talking about time. The photographic act is based in a desire to capture a moment. But there’s more to it than that. With film photography, much time and thought go into each shot. Now add in the five hours typically spent in a given darkroom session. These days professional and amatuer photographers are often driven by the need for efficiency. We fill our memory cards to capacity to give ourselves options, often far too many of them. With a digital camera in hand, we work quickly, as the expected turnaround time continues to diminish. In a world where we are what we ‘Gram, the time between the shot and the post must be nothing short of ‘Insta.

Photo from the UMOP Facebook page.

These are the types of conversations you can expect when spending time at UMoP. But as Svinarski and Longworth guide me through the rest of the space (lab, photo studio), the topic shifts to teaching and providing services to local film photographers. UMoP classes do not follow the typical community education model. Instead they harken back to the European atelier model of studying under a known and respected master. While some aspects of this model may seem problematic and exclusionary, it does offer benefits for both the master and the student.

The UMoP website contains the following tagline: Photography is our passion. At first glance these words may seem a bit overblown or overused. But for the humans of UMoP, and the community they continue to cultivate, these words are true. Enrollment in UMoP training requires an in-person meeting. This meeting has three goals: to determine passion, commitment, and the makings of a unique point of view. If one displays these qualities, they can expect a deeply engaging and demanding experience that is part apprenticeship, part BFA in Photography. Svinarski will match your commitment inch for inch. Skills and techniques can be taught and learned. A point of view can not.

Photo from the UMOP Facebook page.

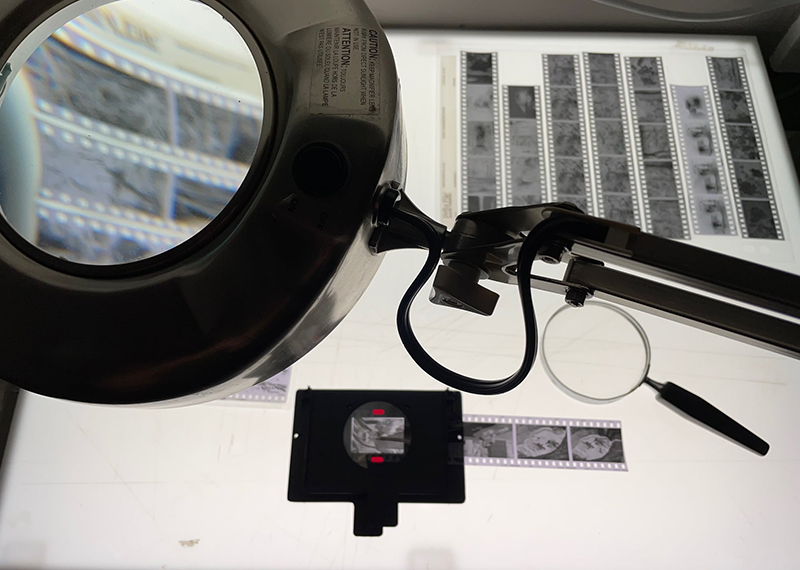

UMoP holds the distinction the of being the only lab in the area that processes color film. In addition to this they offer a wide range of services including black and white processing, custom silver gelatin processing, film negative restorations and scanning. Additional services are in the works. UMoP has managed through the pandemic by offering contactless film drop and delivery, with the assistance of their website.

Longworth shared that upcoming website features will allow customers to make customized processing requests (e.g. corrections) and for the UMoP humans to communicate questions and suggestions throughout the process. Longworth, who curates UMoP lovely and informative social media presence, also shared that pop-ups, as well as new gallery exhibits, are in the works, although events, like classes, are launched according to inspiration rather than tethered to a specific schedule. See social media and website links below to learn more.

Photo from the UMOP Facebook page.

As we wrapped up, Svinarski and Longworth, looked out the window, commenting on the changing light and color, and the possibility of rain. I faced the window and for a moment or two we watched. This is what a photographer does. She takes her time. She pays attention to the light and the angles. She established a point of view. I found myself thinking back to the notion of time and choices. If you could only have 24 frames (of film), what would you choose? And wouldn’t this cause you to stop and think rather than just react and push a button. In our current Zoom-based interactions, and constant stream of digital updates, film photography is a form of meditation. Some chefs offer slow cooking as a tonic for the times. At UMoP, I experienced the zen of slow photography.

And while I strongly suggest that you make an in-person visit to UMoP, you can also enjoy a virtual tour video on Facebook.

The Urbana Museum of Photograph

113B North Race Street, Urbana

217-649-5605

Learn more on the UMoP website, or follow them on Facebook and Instagram.