I met Mike Pingleton at The Blind Pig Brewery (where we had Great Lakes Edmund Fitzgerald and their own Samburro Chili Ale & Cherry Milk Stout, if you must know) so we could talk about his interest in herpetology and his recent writing career. First, I asked him to define the slang word “herp,” (#2 & #5) which is heard often in the herpetological community.

herp – n. A reptile or amphibian.

herp – v. To go out and find reptiles and amphibians; to go herping.

Pingleton explained that searching for the polarizing animals is very much akin to bird watching, but also different. “The idea,” he said, “is to go out and to see the organism, not to kill it or take it home, but to observe it and take pictures. Just getting outdoors and enjoying nature, exploring exotic locations. There’s much more to it, though. You can be a part of scientific projects and take data; there’s a photography element to it. Herp photography is an art and science unto its own.”

Pingleton, who hails from St. Louis and has worked at the NCSA for the last twenty-three years, first developed an interest in herpetology at age twelve. “I found a snake in my back yard and sort of got interested from that point on,” he said. “It just sort of kindled an interest in those kinds of creatures. I’ve spent a lot of time outdoors looking for them over the years.”

Why herpetology in particular, he can’t really say. “I’ve been exposed to other animals that I still have great interest in, but there’s something about herps. With herps, there’s an element of discovery that you can’t have with a bird. You can see a bird on a tree or a fish in water, they’re much more elusive creatures. You can lift a rock and find a snake or a salamander. You can hold it and take its picture and take it home, or you can put it right back. You have more immediate contact with that animal. It’s more personal than looking at a bird through binoculars. It might even bite you. All kinds of things can happen.”

Why herpetology in particular, he can’t really say. “I’ve been exposed to other animals that I still have great interest in, but there’s something about herps. With herps, there’s an element of discovery that you can’t have with a bird. You can see a bird on a tree or a fish in water, they’re much more elusive creatures. You can lift a rock and find a snake or a salamander. You can hold it and take its picture and take it home, or you can put it right back. You have more immediate contact with that animal. It’s more personal than looking at a bird through binoculars. It might even bite you. All kinds of things can happen.”

“I don’t want to say it draws a specific type of person, but in my circles in terms of people that I spend time in the field with, they come from all walks of life. They’re professors, biologists, truck drivers, and computer people like me. I can’t really pin them down except they’re people who all like a specific kind of living organism.”

Personal note: I’ve actually grown up with caged snakes in my house, so they’re nothing new to me. One thing I’ve noticed over the years is how just about everyone “knows everything” about snakes, kind of like everyone putting their own personal spin on the intricate science of personal health.

I asked why this was, and with snakes specifically. He said that a fear of snakes is atavistic. People have seen snakes as a threat forever. As a result of this, Mike said, “You’ll get people who tell you the most ridiculous stories about snakes, but you can never dissuade them because it’s important not just for them to be right all the time, but that they think they have all the facts and they’re in control and that they understand it.”

I asked why this was, and with snakes specifically. He said that a fear of snakes is atavistic. People have seen snakes as a threat forever. As a result of this, Mike said, “You’ll get people who tell you the most ridiculous stories about snakes, but you can never dissuade them because it’s important not just for them to be right all the time, but that they think they have all the facts and they’re in control and that they understand it.”

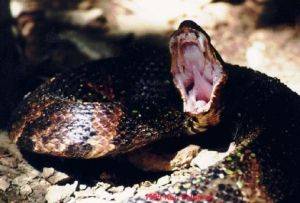

Pingleton’s favorite ridiculous story: “It’s the friend of a friend who was water skiing and went right into a nest of cottonmouths. That story is apocryphal. I’ve heard it maybe not a hundred times but dozens of times. It’s always ‘a nest of cottonmouths.’ There’s always this common phrase. It’s not always water skiing, but the phrase ‘nest of cottonmouths’ always comes into the story. It’s interesting because this whole little myth even makes it into popular culture. The Lonesome Dove series has some incident where somebody is in the river and gets in a nest of cottonmouths. It’s sort of a ridiculous thing because cottonmouths don’t nest and you’ll more than likely never see one in the water. That’s my favorite one.”

And with an interest in herpetology also came a thirst for more knowledge on the topic. Pingleton first read the Golden Guide book series and eventually the Peterson Field Guides to learn more about the animals. His book collection on the topic has grown since, some even with his name on their covers.

Writing was something he was always interested in, and spurred on by his work at the NCSA. His transition into writing made him into a pioneer in online herpetology, and one of the earliest bloggers.

“It sort of ties back to where I work and what I do. In 1993 we at NCSA had the guy who invented the Mosaic web browser and so we were encouraged to understand and utilize this new media. In 1994 I built what I would call my first herp page. It was actually the first reptile and amphibian page on the web, and it’s still there. In 1996 I decided to start keeping journals of trips I made. There were no tools, you had to use HTML code for everything. It was difficult but a lot of fun because it was new and different and a few people started to do the same thing. It was kind of fun to be at the forefront of that.”

Pingleton’s website led to other projects, eventually a book on the care of red-foot tortoises. He had adopted a group and realized there was no literature on the topic. So he did the research and published his own book.

Pingleton’s website led to other projects, eventually a book on the care of red-foot tortoises. He had adopted a group and realized there was no literature on the topic. So he did the research and published his own book.

“It took me a year and a half to write it,” he said. “I wrote it and rewrote it and edited it and figured out many things along the way, such as the writing process and editing process, and then put that out as a self-published book. And it did pretty well, and it still does pretty well on Amazon.”

The tortoise book was only the first step. Pingleton had also been interested in poetry, and through an online community called “The Banyan Tree” was able to connect with like-minded individuals and learn the craft of poetry.

“They were saying ‘When are you going to put out a book?,’ and I never really considered it because, like many people, I didn’t think my work deserved that step; but a couple of these folks just bugged me and bugged me. When self-publishing came around I thought I’d throw some of these together, and I really enjoyed the creative process, choosing the poems, the ones for the book. It’s been a great experience because I’ve learned so much about the creative process.”

Most recently, Pingleton has worked on a series of e-books for children entitled Kid’s Book of Cool Snakes and Kid’s Book of Cool Frogs and Toads. Despite his extensive knowledge and experience on the topics, writing for a younger audience hasn’t been a trip down easy street. “One of the most difficult things is trying to write for children,” he told me.

Most recently, Pingleton has worked on a series of e-books for children entitled Kid’s Book of Cool Snakes and Kid’s Book of Cool Frogs and Toads. Despite his extensive knowledge and experience on the topics, writing for a younger audience hasn’t been a trip down easy street. “One of the most difficult things is trying to write for children,” he told me.

“I like the word cool because it’s retained the same meaning over time,” he said. “I wanted to show them a cool animal and tell them why it’s cool. Pictures were the easy part, but it was hard to come up with text. Who am I writing for? I like to think I’m writing for an 8-year-old or 10-year-old. I don’t want to make it too simplistic or too technical.”

“I sat down in a quiet place and tried to get in touch with my inner eight-year-old. Here’s, for an example, a hognose snake, an animal I’ve known for 40 years; it’s old stuff to me. How do I get what’s ‘cool’ about it from where I’m at now back to that kid who’s maybe heard of them but never seen them? How do I get to that point? That was the biggest challenge of preparation. I had to sort of get over being blasé about them. Not that I’m bored of them, but after seeing hundreds of them, it’s hard to get in touch with that excitement again.”

Pingleton’s goal with the children’s book series is to present interesting facts to youngsters, not in too technical a way but also not too simplistic. He would like to do more, but said the online publishing market is unstable, and it’s hard when companies don’t help with promotion. Also, the formatting: “You have different formats for different tablet devices. If you did one for iPad it would look great, but terrible for Kindle.”

Regardless of the e-book market, he said he is also interested in putting out another poetry collection. It’s just a matter of having enough ideas and new material, he said. And on self-publishing as a whole, he said, “It’s a lot of work for not so much money. If I looked at it as a part-time job, it would be a couple bucks an hour.”

He’s also working on a new field herping book, and all of his other works can be found on Amazon.