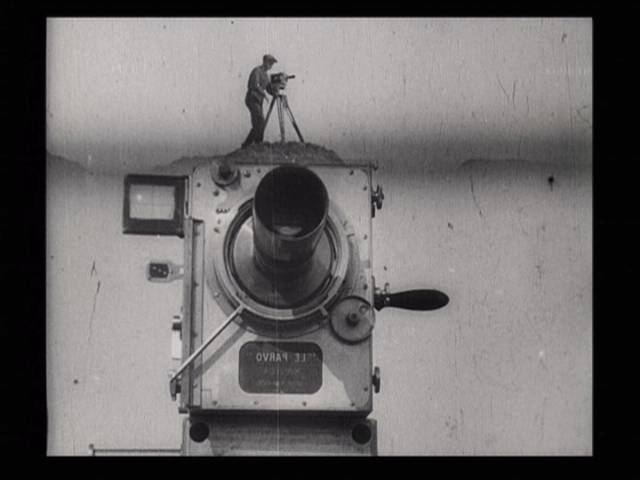

In 1929, Russian director Dziga Vertov released Man with a Movie Camera, an experimental silent documentary depicting daily life in Russia using a wide variety of cinematic techniques. The “man with a movie camera” is frequently interjected into many of these events; in one instance, the camera captures a train speeding towards it. In a reverse shot, the cameraman is shown positioned safely beneath the tracks. Another sequence features a tracking shot of the same cameraman standing with his tripod on the back of a moving automobile. The cameraman is certainly a prominent character in the film, but there is no story. Vertov felt that the cinema was too indebted to the theater and literature, so he set out to demonstrate that film could work on a different level.

In 1929, Russian director Dziga Vertov released Man with a Movie Camera, an experimental silent documentary depicting daily life in Russia using a wide variety of cinematic techniques. The “man with a movie camera” is frequently interjected into many of these events; in one instance, the camera captures a train speeding towards it. In a reverse shot, the cameraman is shown positioned safely beneath the tracks. Another sequence features a tracking shot of the same cameraman standing with his tripod on the back of a moving automobile. The cameraman is certainly a prominent character in the film, but there is no story. Vertov felt that the cinema was too indebted to the theater and literature, so he set out to demonstrate that film could work on a different level.

Man with a Movie Camera is a must-see for anyone with an appreciation for film history and one of the selections this year at Ebertfest. Accompanying the film will be the Alloy Orchestra, performing their original score for the film. The Alloy Orchestra is comprised of three members: Roger Miller on keyboards, Terry Donahue on the accordion, musical saw and assorted junk percussion, and Ken Winokur on junk percussion and the clarinet. Winokur also acts as the director of the band. I had the chance to speak with him about the Alloy Orchestra’s musical contributions to silent films.

(left to right: Donahue, Winokur, Miller)

Smile Politely: First of all, I just want to mention that it’s kind of funny that you’re called the Alloy Orchestra. I hear the word “orchestra” and it conjures to mind this image of a large group of people dressed in suits playing these very traditional instruments and here you guys are playing this junk percussion set-up. So I have to ask, why do you prefer junk over traditional instruments?

Ken Winokur: Well, we do play junk but we also play traditional instruments. We play anything including synthesizers, so we’re reproducing a lot of orchestral sounds. We sound like orchestra — a very percussion-heavy orchestra [laughs]. And Man with a Movie Camera is one of our more percussion-heavy scores

So here’s the explanation of it: Man with a Movie Camera was directed by Dziga Vertov, who was a Russian filmmaker. Before he became a filmmaker, he was a student at a music conservatory where he studied Russian Constructivist music, which involved taking, what was called, musique concrete, sounds from the real world, and inserting them into his compositions. His directions to the composer who did the premiere of Man with a Movie Camera in 1928 had things like that in it. The film itself shows the orchestra. The percussionists have a little set-up with a bunch of empty bottles, a washboard, and a pile of spoons. And that was the whole orchestra. They called it the “bottle and spoon orchestra.” We reproduced the exact same thing — I got bottles, spoons, tin plates, wash tubs, and all this stuff. So that’s a good example of junk percussion. It really is rooted back in the time of the silent film, but it’s also just what we do. I’ve done it forever, in every band I’ve ever been in. There’s a much wider palette than regular percussion.

The palette of a drum set is so limited; it has about six or seven major sounds. Our drum sets have hundreds of sound capabilities and that’s what we need for the movies. We do some of the sound effects. If a guy is sawing and you don’t want to bring a saw with you, you can use a piece of electrical conduit. And that was a typical orchestra’s job. Many of the traditional film orchestras had percussionists who played sound effects along with the movie. We’re doing that in a traditional way but we’re doing it in a somewhat non-traditional fashion since we’re using an electronic synthesizer. We see no reason not to use stuff that has developed over the 20th century.

SP: Is your collection of instruments, then, always growing?

KW: Well, the problem is transportation. Anything new requires new airline baggage. We used to be expansive with this and now we’re being reductive. Oddly, this is affecting our sound somewhat. The airlines aren’t really allowing us to bring very much stuff and we have to fly to Ebertfest. So we have to be very considerate of what we’re going to bring. So now our scores are starting to be more and more melodic. Terry [Donahue] plays accordion and the musical saw and I play clarinet. These are becoming more prominent now in our scores.

SP: Do you have any particular musical influences?

KW: The music that we have been playing in all of our bands, all over the United States and Europe for decades brought us together. Our first film was Metropolis (1927) and that was a very modern film — it’s set in 2034, I believe. So anything in contemporary music you can draw inspiration from would be appropriate for that film. But other films are not necessarily like that. Every film needs its own stylistic approach to it. When we approach Man with a Movie Camera, we can use more of the junk percussion, avant-garde rhythms, interesting key structures, and synthetic sounds. We even use radio frequencies with a short-wave radio as part of the background in the film. We really try to direct our scores to support whatever film it is we’re playing. So if you’re doing an avant-garde film, it’s OK for you to go wild because that’s what the director wanted. But every film is different!

SP: Man with a Movie Camera is definitely a more experimental, less linearly structured film, so did that give you a chance to play around some more and try out new or different things?

KW: Yes. And we also had the benefit of having Vertov’s notes for his composer that had recently been translated and that nobody had really seen at this point. We also had two Vertov experts from the George Eastman house at the University of Chicago that came into our studio while we were composing: Paolo Cherchi Usai, the senior curator at the time of the George Eastman house archives, and Yuri Tsivian. While we were composing, they were coming up with explanations of Vertov’s manifestos about the use of radio frequencies. They were also interpreting the notes on Russian patriotic songs that were indicated in the music and giving us an explanation of what that sounded like.

SP: Tell me about how you go about acquiring rights to showcase these films.

KW: Well, that’s a good question because it’s a big issue for us all the time. We basically work with the person that is the rightful owner of the film — in this particular case it was the Moscow Film Archives. They have a policy that they will sell a copy of the print to archives or people that will use it reasonably. So they sold us a copy of the film. We own a couple films and it is enormously beneficial for us to be able to travel with our own copies of the film. But, for the most part, we have to rent the films.

SP: Do you ever run into any copyright issues or other problems concerning the rights of the films you use?

KW: There’s a problem sometimes when copyrights are set by studios, a lot of which are still active today and making big blockbusters. They are often not that responsive to these old films that they own. They don’t really care about them.

SP: But you still have to jump through some hoops to even get access to them, I bet.

KW: Exactly. There are exceptions, though. We found that Paramount Pictures actually has this fabulous archive. So we try to accommodate them and they are really great about lending them to us at a reasonable rate. But we mostly try to work with private collectors.

SP: And since you have access to these old films, do you feel like part of your role, in addition to scoring the soundtrack, is also making these films more accessible to modern audiences?

KW: The way you put that is really great because that’s often the exact phrase that we use — we make the films more accessible to modern audiences. We act as a bridge from a time that is now very long ago, 75 to 100 years, to modern audiences. Musically, that is often how we approach it. We are willing to do anything that our modern audiences will find acceptable within the context of that film.

SP: Do you ever find that there is something in an original score that really seems to work so you try to carry over that element in your score?

KW: We work in the opposite direction. We try to avoid using influences like that in our music by rehashing not someone else’s music. With some exceptions, such as material specifically called for by the director.

SP: Do the scores ever evolve? I mean, you can watch a movie for the 20th time and you’ll see something new that strikes you in a different way than it has before. Does that ever happen with you and then, does the score change to reflect that?

KW: Absolutely. Our scores are always changing. We’re improvisers by nature and training. When we’re composing, we will actually sit in a room and improvise together and that’s where the music comes from. Throughout the shows we’re always fine-tuning our parts and adding in certain sections. It really is a living organism.

SP: So it’s a pretty collaborative effort then between you, Roger, and Terry?

KW: It is. Absolutely. We all get together and contribute any idea that comes to mind.

SP: Is there ever any improvisation in the live setting?

KW: Yeah. We do a lot, actually. We know the films so well that we know when a cue is coming up and that we have some freedom in that space.

SP: So then, I’m sure there is also stuff you liked originally that may not work anymore.

KW: The newest film we are working on, Metropolis, is actually our oldest film, so there is a lot of that. After 20 years of working on a film, there are a lot of changes. For instance, I brought the clarinet in for the new version of Metropolis because I have been playing the clarinet for the past 10 years and was not when we originally wrote the score. We have scored several different films twice and we’ve worked on Metropolis four different times.

SP: Back to a more basic question: how long does it take to write and prepare the music for a premiere?

KW: We probably go through the films at least 25 times during rehearsals and maybe 50 to 100 times for our individual parts. It takes around three months to write and rehearse before a premiere.

SP: What sort of role do you play in live performances? Will the audience be able to see you perform and watch the film as well?

KW: Yeah. There’s usually a little bit of light on us and we’re usually off to the side of the stage so people can see us quite well. More than half of the time we’re actually on the stage but there’s not room for that at [the Virginia Theater]. We’re harder to see in the orchestra pit but everyone can still see our heads, our sticks, and the junk rack. And we’re a mobile art installation as well, I’d like to think. We’ve built [the junk rack] over the years and it’s always getter grander and lesser so it’s an interesting visual art experience as well.

SP: Is there a particular piece of the rack that’s a favorite of yours or something that people respond to?

KW: Well, there’s an obvious answer to that. We have a bedpan and it’s followed me around for almost thirty years. It’s become our iconic piece of junk metal. Sometimes we don’t bring it. It has a very harsh sound. Every now and then we use it for shows and people come up and say, “It’s the bedpan!”

SP: Any final thoughts?

KW: Well, I’d like to say something about Ebertfest. We play a lot of film festivals and this one is just extraordinary in every way. The Virginia Theater is huge, a lot of people get into the films, and then there’s Roger up there on the stage. This is Roger Ebert’s festival — it’s where the Midwest comes together and is at its best.

——

The Alloy Orchestra is performing their score for Man with a Movie Camera live at Ebertfest this Friday at 4:00 PM. For more information, visit the Ebertfest website.