There is something downright biblical about Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven. In addition to being one of the most beautiful looking films I’ve ever seen, it has the pace, deliberateness, and inevitability of a parable told to (and, in this case, by) a child. This is the parable of the rich man and his wife, laid out for us by the pre-teen narrator Linda.

The story is set in 1916, in the days before a World War, and is told with a child’s simplicity. By this I do not mean that the film is simple, merely that Linda’s understanding of what she sees and experiences has a cut-and-dried quality. This happened, then This Happened.

The story is set in 1916, in the days before a World War, and is told with a child’s simplicity. By this I do not mean that the film is simple, merely that Linda’s understanding of what she sees and experiences has a cut-and-dried quality. This happened, then This Happened.

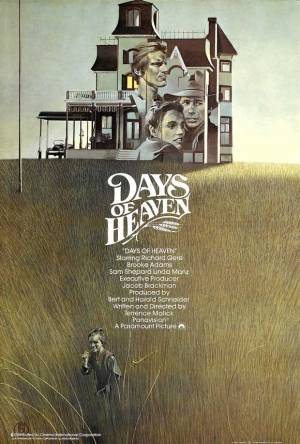

And what happens, basically, is this: Bill (played by Richard Gere) accidentally kills his Chicago steel mill foreman and goes on the lam with his girlfriend Abby (Brooke Adams) and his kid sister Linda (Linda Manz). Linda explains in voiceover that Bill told everyone they met that he and Abby were brother and sister so people “wouldn’t get ideas.” That may be; it also makes it easier for Bill to get ideas of his own.

Arriving by train in Texas, Bill and the ladies find work in the wheat fields of a rich farmer (played by Sam Shepard). The work is hard and unrelenting, but the scenery is extraordinary. It’s so beautiful out in these windy, golden fields, that the rich farmer spends most of his time outside with the workers, finally taking a shine to Abby, going so far as to ask her to “stay on” when the work season is over. When Bill overhears a visiting doctor tell the rich man that he has only a year or so to live, a plan takes shape.

For anyone who hasn’t seen this gorgeous 1978 film, I won’t spoil the ending. But suffice it to say that things don’t work out.

The plot of Days of Heaven, which opens this year’s Ebertfest on Wednesday, April 17 at 7:00 p.m., is interesting and watchable, but the true beauty of the film lies is its visuals. Much of the film is practically wordless, the light and shadow and great expanse of the Texas Panhandle telling the story in ways that dialogue might complicate or ruin.

The scenes between the actors are more vignettes than anything, usually lasting only a few seconds and rarely with more than a couple of lines spoken. The words they do speak are a lot like the atmosphere of the farm: flat, but not without depth; hard, but not without beauty.

As the farmer, Sam Shepard is like a lanky boy in a man’s suit. He has a lean  handsomeness that fits the farmer’s prognosis, as well as the nervous, fidgety quality of a man who can’t trust anyone, including himself. He is forever checking the weather vanes and wind instruments on the roof of his enormous house. From up there, he is a king surveying his kingdom as well as a prisoner, never quite sure which way the wind is blowing.

handsomeness that fits the farmer’s prognosis, as well as the nervous, fidgety quality of a man who can’t trust anyone, including himself. He is forever checking the weather vanes and wind instruments on the roof of his enormous house. From up there, he is a king surveying his kingdom as well as a prisoner, never quite sure which way the wind is blowing.

As Bill, Richard Gere is all dark lashes and soft menace — a beautiful façade with a darkness underneath. The brooding masochist. The scheming, self-destructive martyr. None of the characters in this film speak much, but his performance could have been silent and still powerful, his expressive face and physicality conveying every message.

In the role of Abby, Brooke Adams has the odd distinction of being both the instrument of deception and the story’s moral center. She does not seem an evil person, nor does she seem indifferent to the farmer’s plight. She has seen a lot, lived a hard life, and simply wants something more. She is an object of desire who, while quite striking, is somewhat less beautiful than the men who wish to possess her.

In the role of Abby, Brooke Adams has the odd distinction of being both the instrument of deception and the story’s moral center. She does not seem an evil person, nor does she seem indifferent to the farmer’s plight. She has seen a lot, lived a hard life, and simply wants something more. She is an object of desire who, while quite striking, is somewhat less beautiful than the men who wish to possess her.

Toward the end of the film, when the wind shifts and things begin to fall apart, the biblical nature of the story becomes sharper but never quite heavy-handed. There is pestilence, and there is fire. And there is death.

At one point in her narration, young Linda says, “The Devil was on the farm.” She is not referring to Bill, who while technically a killer seems more a victim of hard life  circumstance, a man more interested in surviving than in “having it all.” In this film, as in many allegories, the Devil is the person (or opportunity) that allows us to have what we desire most, at a terrible cost.

circumstance, a man more interested in surviving than in “having it all.” In this film, as in many allegories, the Devil is the person (or opportunity) that allows us to have what we desire most, at a terrible cost.

When the fire comes, it is a cleansing fire, and Shepard’s farmer is a king who has grown sick of his kingdom. His actions and conclusion ask the question, How long do you stand in the midst of the fire, swinging at it, before you finally decide the flames are too high and just let it burn?

I can think of no better way to begin this year’s celebration of Roger Ebert and his exquisite taste in movies. In the usual grab-bag of tense thrillers, oddball comedies, foreign films, and independent releases, Days of Heaven is a visually captivating work of art, a testament to how well the camera can tell a story … and teach a lesson.