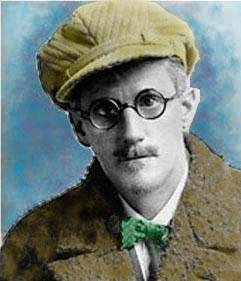

This amateur guide to James Joyce is intended to do two things: First, to introduce this Modernist literary master to the Philistines out there who have either never read or never heard of him and, secondly, to delineate the books into four levels of increasing pain and frustration.

This amateur guide to James Joyce is intended to do two things: First, to introduce this Modernist literary master to the Philistines out there who have either never read or never heard of him and, secondly, to delineate the books into four levels of increasing pain and frustration.

Part Four – The Advanced: Disorientation, loose stool and dementia.

After the publication of Ulysses in 1922, Joyce was so drained that he did not write for a year. When he finally put pen to paper, he began work on what would be his last novel. He wrote and revised it for fifteen years, longer than some marriages. During this period, Joyce’s eyesight deteriorated. His daughter, Lucia, suffered mental health problems. In 1931, his father John Joyce died. Despite the emotional roller coasters, Joyce continued to write and persevere.

He kept the title of his new novel under wraps. Parisian literary journals published bits and pieces of it under the title “Work in Progress.” The completed version, Finnegans Wake, made it to print in 1939. Some people applauded the book, calling it a masterpiece of experimental prose and style. Many critics hated it.

The modernist poet Ezra Pound, longtime friend and supporter of Joyce’s, thought it pretentious.

“Nothing so far as I can make out, nothing short of divine vision or a new cure for the clapp can possibly be worth all that circumambient peripherization.”

He was referring to Joyce’s use of an amalgamation of European languages and literary references in creation of portmanteau words and phrases:

“Mischnary for the ministrary to all the sems of Aram. Shimach, eon of Era. Mum’s for’s maxim, ban’s for’s book and Dodgesome Dora for hedgehung sheolmastress. And Unkel Silanse coach in diligence.”

Each word had a double or triple meaning; every sentence held a wealth of complexity. “Jabberwocky,” from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, is also rife with portmanteau words. Slithy = slimy + lithe. Chortle = snort + chuckle. ‘Frankenfood’ and ‘motel’ are modern examples.

In addition to the unfamiliar syntax, Wake had a few other anti-personnel devices: A cyclical structure, daedal puns, and probably more than a few inside jokes thrown in for confusion. The starting point was arbitrary. The book’s last sentence was the beginning of the first.

Serious Joycean scholars seem to believe that Wake has characters and a plot. It’s true, some of the same capitalized words that might be names pop up regularly, but there’s no semblance of a discernible plot. If one semi-coherent sentence makes you think that you’ve grasped a thread of understanding, Joyce rips it from your hand and laughs in your face for the rest of the paragraph.

One plausible theory about Finnegans Wake is that it’s a novel about a dream. It may be a dream shared by five fictional characters, but it makes about as much sense as the one where you fell down a flight of stairs and wound up sitting at a desk in the back of your high school chemistry class while a dog pointed to the periodic table of elements and spoke in a language you didn’t understand, but it sounded Slavic. Even more boring than listening to a friend describe the dream he had the night before is reading one. In its entirety. No matter how highbrow and allegorical.

Unreadable as Wake may be, it and Joyce both deserve a grudging respect for the sheer magnitude of intricacy and deep thought involved. Do not attempt to read it without a Sherpa or jungle tracker. A guide book at the very least. They are legion. Try A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake by Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson.

Even with the guide, reading Finnegans Wake is a Herculean task. Don’t try it unless you’ve set aside a few months of your life, a few pints of single-malt and a family-sized bottle of aspirin.

If you enjoyed this, see also Lindy’s Essential Joyce Part I, Part II, and Part III.