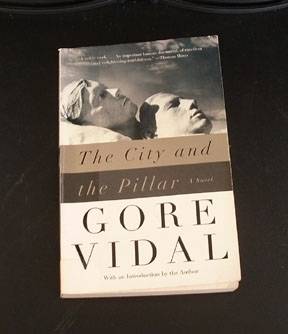

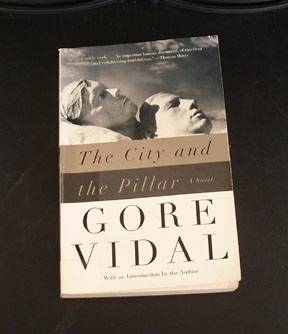

Ah, to be alive in the ’50s: the wonders of the new interstate highway system, the convenience of modern appliances, the crippling need to conform. Sure, being a rebel without a cause was cool, but there were limits. Certain cultural “inversions” were either never discussed or dismissed with a sneer. The 1948 New York Times review of Gore Vidal’s novel, The City and the Pillar, rejected the work, calling it a “case history of the standard homosexual,” and further insulted it by flying over the major plot points at a cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. There is much more to this novel than The New York Times reviewer would admit.

Ah, to be alive in the ’50s: the wonders of the new interstate highway system, the convenience of modern appliances, the crippling need to conform. Sure, being a rebel without a cause was cool, but there were limits. Certain cultural “inversions” were either never discussed or dismissed with a sneer. The 1948 New York Times review of Gore Vidal’s novel, The City and the Pillar, rejected the work, calling it a “case history of the standard homosexual,” and further insulted it by flying over the major plot points at a cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. There is much more to this novel than The New York Times reviewer would admit.

The literary stereotypes for gay characters until that time relegated them to a few categories: Exceedingly effeminate, transvestites, or studious outcasts who married but harbored a secret desire. In order to challenge the prevailing stereotypes, Vidal’s main character, Jim Willard, is purposefully their opposite. He is masculine. He is an athlete. He is in love with his best friend, Bob Ford, also an All-American man’s man. Their first sexual encounter takes place on a camping trip just before Bob graduates from high school and takes to the sea.

“Two bodies faced one another where only an instant before a universe had lived; the star burst and dwindled, spiraling them both down to the meager, to the separate, to the night and the trees and the firelight; all so much less than what had been.”

This is the only instance of anything approaching poetry in the whole of the novel. Jim’s first experience with Bob turns out to be the only sexual experience that leaves an indelible mark. His subsequent encounters pale in comparison. Vidal conveys this stark reality through dispassionate prose describing the years of Jim’s life without Bob. The intervening sexual experiences are never mentioned in any detail, merely implied. Besides his later partners, Ronald Shaw and Paul Sullivan, the others are faceless and innumerable. These men are only placeholders, time-killers, until Jim reunites with Bob.

This is the only instance of anything approaching poetry in the whole of the novel. Jim’s first experience with Bob turns out to be the only sexual experience that leaves an indelible mark. His subsequent encounters pale in comparison. Vidal conveys this stark reality through dispassionate prose describing the years of Jim’s life without Bob. The intervening sexual experiences are never mentioned in any detail, merely implied. Besides his later partners, Ronald Shaw and Paul Sullivan, the others are faceless and innumerable. These men are only placeholders, time-killers, until Jim reunites with Bob.

After stints as a cabin boy, tennis instructor, and Air Corps physical fitness trainer, Jim returns home to Virginia and learns that Bob has returned home as well — with his wife. The two men meet and speak of old times. The real reunion happens later, in a hotel room in New York. It is far from the magical experience Jim built up in his mind during their years apart. In the 1948 version of The City and the Pillar, Jim kills Bob after their failed sexual encounter. Vidal rewrote the ending in 1965, softening Jim’s retribution, though it is no less violent.

Besides the tryst by the river, Vidal siphoned off all emotion and sentiment from the rest of the novel. I didn’t care about any of the characters because they all seemed devoid of any human spark. They trudged through the motions, stiff-armed like Dawn of the Dead extras.

Drawbacks aside, reading this book was well worth the effort. The City and the Pillar was ground-breaking for its time, and Gore Vidal was infinitely brave for writing the novel and publishing it rather than shoving it to the back of a desk drawer in hopes of a less repressive environment than America in the 1950s.

Rating: 3 of 5