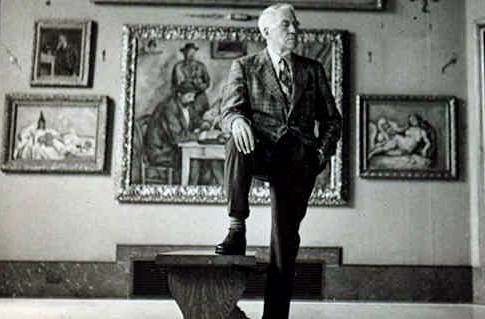

Dr. Albert C. Barnes first came into the national spotlight in the early 20th-century for his invention of Argyrol, an antiseptic used to treat gonorrhea and prevent potential gonorrhea blindness in newborns. It is hailed, perhaps a tad hyperbolically, in the documentary The Art of the Steal as an invention comparable to what a cure for AIDS would be today. Barnes’ contribution to the medical community, however, is not important to The Art of the Steal; that it made him rich, on the other hand, is. Today, his legacy is the Barnes Foundation, an institution in the Philadelphia suburb of Lower Merion that houses his personal collection of Impressionistic, Post-Impressionistic, and early-Modern artistic masterpieces.

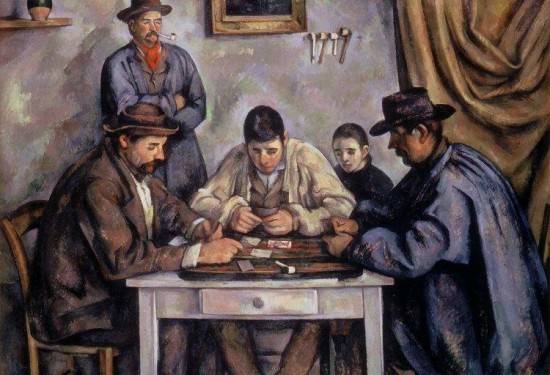

Between his invention of Argyrol and the establishment of his foundation in 1922, Barnes spent his time in Europe rubbing shoulders with artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso and collecting many of their paintings, long before their value would skyrocket. One of his Picassos, according to the film, was purchased for under $100. His collection would eventually include a variety of sculptures, ceramics and, most significantly, over 800 paintings by artists such as Matisse and Picasso, as well as Van Gogh, Claude Monet, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and more. Many art critics say that the collection is priceless. Those who want to be more specific have estimated the value to be around $25 billion.

Barnes created his foundation not as a museum but as an educational institution for art students. The film goes to great lengths to create contrast in this regard: while the works in the Philadelphia Museum of Art often sit alone, save for a label, on massive bleach-white walls, the art in the Barnes Foundation gravitates together creating a pastiche of smaller works punctuating larger compositions. A variety of sculptures and other bibelots decorate otherwise negative space, as if the wall itself were a canvas. Barnes was not interested in the mere presentation of a work of art, but in creating a way in which works could interact with each other; a method that encourages and enhances appreciation.

When Barnes first exhibited his collection to the public, it was received with scathing reviews from art critics and called, among other things, “primitive”. One visitor even remarked upon leaving that he had “seen enough naked fat ladies.” Afterwards, the collection remained open exclusively for students. As the value of the works appreciated, critics and the public demanded access, to which Barnes replied with an emphatic “no”. His disdain for the alleged Philadelphian-artistic-elitism drove him to shun public attention and even stipulate in his will that the collection never be moved or otherwise adulterated.

The Art of the Steal focuses most of its attention on the time following Barnes’ death in 1951, as a series of convoluted legal events unfold threatening the fate of the art that Dr. Barnes outlined in his will. The art is taken for tours, the foundation is open to the public, and now, it seems the art may finally move to a larger venue in downtown Philadelphia through questionable and possibly illegal actions on the part of a couple of nonprofit organizations. In short, they were able to wrench control from those who were serving Barnes’ interests and seize $25 billion worth of art.

Director Don Argott’s filmmaking was able to capture many of these proceedings as they developed, giving the film an effective sense of immediacy and allowing him to film many of his pro-Barnes subjects while their passions ran at what surely was an all-time high. This enhances the subject matter for those in the audience with ambivalent opinions concerning the fate of the art, but it also comes with its faults: those in the film that support the move of the artwork often seem certain of the integrity in what they are doing while Barnes’ supporters occasionally engage in a more inflammatory, off-putting discourse.

The film also raises some interesting issues concerning art as a commodity; specifically, does the public have a right to see this priceless art, or can it be used exclusively as an educational tool so that we may invest in our own future artists instead of exhaustively praising artists of the past? If the public truly does have a right to see this art, is it then ethical to turn a quick buck on it? Why should I not have the opportunity to see Barnes’ collection just because he wished for his art to remain as is? Is that not elitism? The Art of the Steal never fully addresses these questions.

However, it does present a damning indictment of the way in which politicians and those with clout can thwart a man’s dying wishes in order to serve their own self-interest. Barnes certainly had a better idea of how to manage art then people like that.

The Art of the Steal is showing exclusively at the CU Art Theater through Thursday. Visit their website for showtimes. Watch the trailer below: