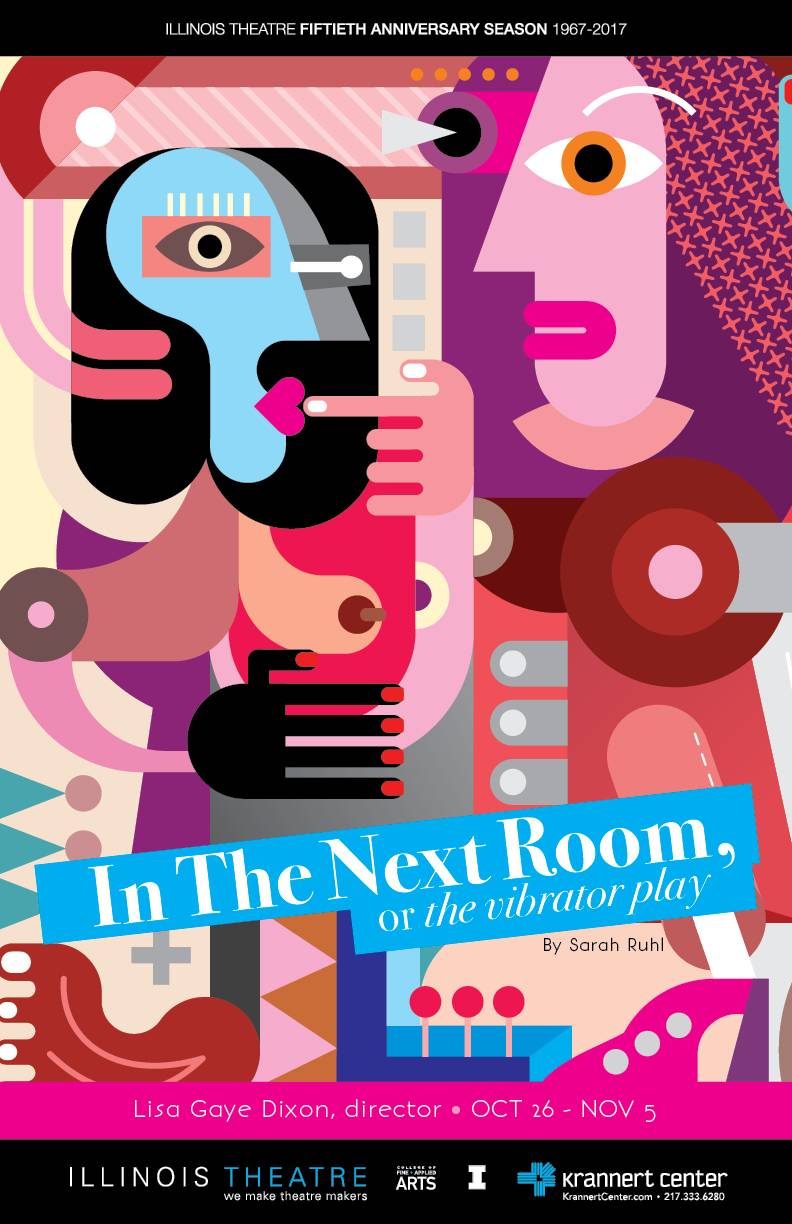

In the Next Room (or the Vibrator Play) by Sarah Ruhl is set in the early days of the vibrator, when it was actually being used by doctors to bring women to orgasm as a cure for “hysteria.” Following Dr. Givings and his wife Catherine as they interact with his various patients, including the sexually frustrated Mrs Daldry, the play deals primarily with the idea of women discovering their own sexual desires, with the help of a little electricity. Winner Nominee for the Tony Award for Best Play, In the Next Room has dynamic characters, entertaining interactions, and a thoughtful ending. I had the chance to sit down with Lisa Gaye Dixon, the director of the upcoming Illinois Theatre production, to discuss the play.

Smile Politely: The play obviously features the theme of female sexuality. What other themes do you see the show touching upon?

Dixon: Well, it’s near the dawning of a new century, in the 1880s. There’s progress, electricity, and what it means to move into an electrified world. The connection that the dramaturg has written about is how this progress impacts the lives of people in every social strata, as well as gender. There’s also an element of communication and status inside a relationship. We see the most traditional or most widely recognized straight, heterosexual, legalized marriage. But the play also asks how does one continue to grow as a human being while still recognizing the constraints with which they have to exist on a day to day basis?

SP: You’re in rehearsals now. Has working with the cast on it changed your perception of the play at all? How?

Dixon: You read it on the page and you think one thing. But once it’s on its feet… Wow there’s a lot of orgasms in this play! It’s not dirty in any way. It’s not salacious. But… yeah… there’s a lot of orgasms. I also knew the humor was there, but it’s good to really hear the humor. It reaffirms that there’s a reason you like the play, even its weird sense of humor. I think many people will laugh uncomfortably, or comfortably and joyously, or not at all.

SP: How was this play chosen?

Dixon: Well there’s the season selection committee, which works year round with people who are directing to select plays for the next year’s season. This is a play I had been wanting to do for a few years, since back when it was new and we finally came around to it. The committee has to make sure you have the possibilities in the student body to be able to do it, of course. But I was asked by the committee to name some plays that I would be interested in doing, and this was on the list.

SP: What made you want to work on this play?

Dixon: I’m interested in the themes within the play, and in all women, but especially young women. And the young women in my care as students. Finding their power. Accessing their power, and using their power. Learning to take up more space. And the way to help them do that is to have them work on the play. In this play, one of main characters is interested in who is she and where she fits in. And she finally come to have more self love and acceptance, which is super important for everyone, but especially for artists.

SP: In the first act, Ruhl includes stage directions commenting on how “these are the days before digital pornography” and how “there is no cliche of how women are supposed to orgasm.” I imagine modern standards of women’s sexuality has been a conversation in the rehearsal room. How did that go?

Dixon: I can’t tell you exactly how the conversation went. But we certainly addressed it. We understood that implicitly and we talked about it. Also, the idea that so much, if not all, porn is for a male gaze. This play is not for the male gaze, but for a human gaze.

We also talked a lot about the many orgasms and worked on them, mostly technically — how to differentiate one from another. There’s also, as the play suggests, different kinds and different people. We deconstruct moments in the play, talk about them in a really point by point, moment by moment way in order to put the whole thing back together. They work and they change and as the actresses grow into their characters, it changes. Nothing is static.

SP: Somewhat along the same lines… We live in a time when porn is extremely accessible and, arguably, increasing violent. We also live in a country where the president has bragged about sexually assaulting women. Obviously, more and more information is coming out about Harvey Weinstein’s actions. Additionally, Betsy DeVos has rescinded Title IX, a measure meant to protect students, typically young women, who have been sexually abused on college campuses. And here you are working with young women on a play about finding your sexuality. How has what is happening in the world made it’s way into the rehearsal room?

Dixon: There’s always conversations about it. Especially about Title IX. I think it would make its way on some level into every rehearsal room. Dealing with personal boundaries, allowing touching between directors, students, fellow actors and talking about that individually or as a group. Sometimes, in the early days, doing table work, we’d have conversations about the connective tissue of larger societal issues. Porn and the way sex is portrayed. Nothing about this play is pornographic, but there’s already students and community members who don’t want to see it or don’t want to be challenged, for religious or moral reasons. So there’s been some strong reaction to it before it’s even gone up.

Years ago, I did A Midsummer Night’s Dream which had nudity. Before we even were in rehearsals, community members were complaining… Americans have a weirdly… we run the gamut from incredibly open and anything goes and being completely ravenous about sex, to the other end of the spectrum, super closed off and not accepting the idea of human sexuality. Unlike most other developed countries, we can’t seem to find the “live and let live as long as no one is being harmed” attitude. We want to dictate other people’s sex lives.

Unfortunately, we had a shortened rehearsal period, so we haven’t been able to delve as deeply into the connective tissues. We spent one week at the table, three weeks on our feet. We talk about it on the fly, as we go.

But we’ve been careful and open with talking about comfortability, whether it’s showing their bodies or showing that moment of release — and that is super ultra vulnerable. We meet their needs. These actors and actresses are participating in a conversation about one of those three things you’re not supposed to talk about — sex, politics, and religion. They’re participating joyfully, and hopefully that transfers to the audience and they feel deeply and laugh. They don’t have to agree with it, but I hope they get something out of it.

SP: Anything else you want included about this play?

Dixon: I think it’s beautiful, and I think it does have some connection to not just our political arena, but how men and women are together, especially on a college campus — dealing with consent, communication, taking up space and finding their own way to say yes and no. I think that’s important especially for university undergraduates to see. I hope they get something out of it basically.