AIDS is an ocean of a subject: full of waves of fear, grief, suffering, and loss, and swirling in the dark regions of what “nice” people don’t discuss around the dinner table, the water cooler, or even in our present-day media. For those who became sexually active in the late seventies to early nineties, it was the ultimate penalty for exploring your sexuality and an almost certain death sentence. In the media and churches of the time, it was viewed by far too many as a divine punishment for an age of promiscuity. But those involved in the initial wave of diagnosis and infection know that this disease didn’t care if you were sexually cavalier or deeply committed to a single partner; it was a disease that devastated then killed, without any concern for the morals or attitudes of its victims. Those who saw friends, family, and public figures succumb were both terrified by the rapid lethal nature of this disease and helpless to protect those they loved from its ravaging effects.

AIDS is an ocean of a subject: full of waves of fear, grief, suffering, and loss, and swirling in the dark regions of what “nice” people don’t discuss around the dinner table, the water cooler, or even in our present-day media. For those who became sexually active in the late seventies to early nineties, it was the ultimate penalty for exploring your sexuality and an almost certain death sentence. In the media and churches of the time, it was viewed by far too many as a divine punishment for an age of promiscuity. But those involved in the initial wave of diagnosis and infection know that this disease didn’t care if you were sexually cavalier or deeply committed to a single partner; it was a disease that devastated then killed, without any concern for the morals or attitudes of its victims. Those who saw friends, family, and public figures succumb were both terrified by the rapid lethal nature of this disease and helpless to protect those they loved from its ravaging effects.

For those too young to remember the devastation of the disease in the 1980s through 1990s, its threat becomes progressively murkier. AIDS is no longer a certain death sentence. Rumors circulate that it will soon be a chronic, but manageable condition. A new generation is faced with a lack of honest information, due to years of George W. Bush’s endorsement of abstinence-only education and ill-informed communities and school systems providing our young people with an increasingly edited brand of sex education that ignored alternative sexuality and non-procreative sex practices. It’s sex ed for “nice” people, and it can result in uninformed choices and devastating consequences.

The academy-award nominated documentary, How to Survive a Plague, is a political history lesson with a definite bias of the good guys and bad guys in the United States government, throughout the initial reaction to the AIDS pandemic. It doesn’t fear pointing out the villains or heroes of the time period. To do it justice in a review, the reviewer’s politics will also surface, so if my reputation has not preceded me with this readership, or if you want a review that gives lip-service to the stance that, “conservatives are way-cool, too,” you might want to stop reading, like, now. For those who remain, I strongly urge you to see this devastating, important, and moving film.

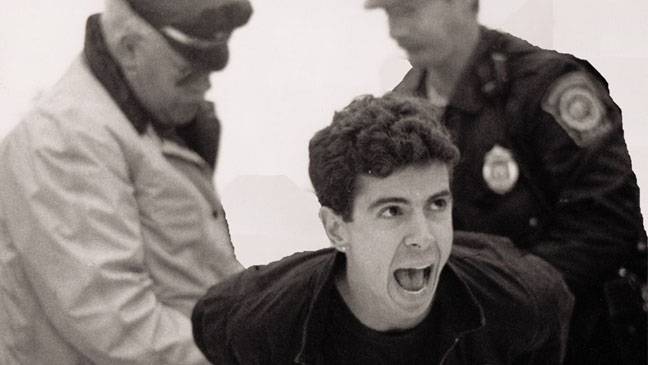

From its initial images of severely ill victims barely clinging to life, How to Survive a Plague paints a powerful and sobering portrait of this disease’s effect on the world from 1986–1996. Beautiful young adults stripped of both their beauty and their basic human dignity struggle to breathe, drink, and take nourishment in a powerful montage that can only be described as “hard to watch.” The film quickly shifts to the actions of those at greatest risk, a group of young activists, many of whom are gay or lesbian, battling to make a sluggish medical and pharmaceutical community and a callous and indifferent government, come to their community’s aid. Playwright and activist, Larry Kramer, activist Robert Rafsky, experimental playwright, Jim Eigo, Dr. Iris Long, actor and activist Ray Navarro, and activist Peter Staley, are a few of the prominent individuals who lead a movement that eventually pressured our government and our healthcare institutions to seriously address the concerns of the HIV+ and AIDS infected community. These are the heroes of this film and the heroes of the movement, according to most reliable sources.

Through a series of news clips juxtaposed with present-day interviews, David France creates a living history of the beginning of political action by a citizen’s group that became Act Up, a national effort to highlight government inaction and promote government awareness and cooperation in the advancement of AIDS treatment. The method may be a standard documentary technique, but France is quite skillful at telling this tale, showing how a series of meetings with at-risk people turns into a national and, later, international movement that spans a decade, ending the certain death sentence of this disease. He builds suspense and pathos through introducing the aforementioned key players of the movement in clips and then making their increasing fear of the disease and their impending mortality infuse life into the humanity of this story. People will survive and people will die in this struggle and, with the exception of Kramer and Eigo, the lives affected are hanging in the balance until the final moments of the film. It’s an effective device that creates an emotional response akin to those who actually endure the early years of the illness. We rejoice with the advent of AZT and, later, feel their disappointment when the drug proves to be an empty hope. With the advent of the protease inhibitors, we see people saved as others are lost and we weep. The statistics of those perishing are also a sober reminder of the cost, as the yearly count moves from 20,303 in 1986 to 6,604,000+ in 1995. We begin to understand how one survivor weeps and questions, “Why did we have to struggle so long for these effective treatments?”

The sinners and saviors are depicted in all their human glory with the villains divided into two categories: those who refuse to act due to governmental inertia and those who refuse to act because of arcane and reactionary moral stances against the disease and its victims. The former category includes Presidents Reagan and Bush Sr., Mayor Ed Koch, Congress, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and many research institutions, such as the National Institutes of Health. People die from red tape and arcane rules for medical testing in this category.

On the other end of the villain spectrum are The Catholic Church officials, shown denouncing sexual immorality and impurity as altar boys serve communion. This visual choice is no accident, as those denouncing the gay population are also embroiled in the church’s cover-up of true horrors that have an equally sobering body count. The truly hateful are represented by Senator Jesse Helms from North Carolina. His diminishing of the disease’s severity and his judgments of those he feels, “should shut their mouths and get on with their business and get their minds out of their crotches” are presented as cruel and harmful, an accurate assessment of this man and his politics. A fossil of a political landscape that condones every –ism that creates division in our society, Helms is ultimately seen as pathetic and clueless, as members of Act Up cover his home with a giant condom in protest of his voting record and hate speech while he looks on in confusion and disbelief. It’s a fitting eulogy to an incredibly harmful political presence.

The heroes are depicted as scared, courageous, and, ultimately, human. My personal hero in this period is Larry Kramer, partially because I appreciate the artistry of his plays and writing, and partially because he states what is true, even when his statements are less than politic. When the Act Up organization’s yearly conference in 1991 is interrupted by a heated debate that results in a divide of the group into two factions, the radically civilly disobedient Act Up, and the tie wearing, rhetorically conservative TAG, Kramer shrieks, “PLAGUE!” to stop the petty divisiveness. “Plague, we are in the middle of a fucking plague, and you behave like this? PLAGUE! Forty million infected people equals a fucking plague, and until we get our acts together, we are as good as dead.” His words are bitter and angry, frightening, and true. Think what you will of him, but Kramer is an impassioned voice of change in our society and he deserves the documentary’s attention and respect. His words and actions shaped a movement that saves lives, and while he may be curmudgeonly and rude, he is also powerful.*

How to Survive a Plague is a history lesson for those who are too young to remember this period and a powerful document of change for those who remember it all too well. The significance of this topic is still immense. One of my best friends is a young man in his thirties from California, whom I met with a group of his friends close to a decade ago. Attractive, articulate, and funny, these young men are a truly special group. They are all intelligent and well-informed individuals, many of whom have worked with various organizations dealing with AIDS education. As of this year, only my friend remains HIV- in this lovely group of young men. It’s compounding personal concerns that is quoted at the end of the film from the CDC stating, “Every four minutes someone in the world dies from an inability to afford the life-saving medications” developed through this struggle. The virus still exists. Intelligence and awareness are not a certain defense. We need to continue to work on ensuring this plague’s end before it affects more of those we love. Please give this documentary your full attention.

How to Survive a Plague plays Monday at 5:00 p.m. and Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. at the Art Theater.