Whether during a meeting, on the phone, or sitting through a commercial break, partially engaged doodling is something that many of us do with frequency. If you’ve ever tranced out while on hold only to discover that you’ve covered your energy bill in an abstract masterpiece to equal Joan Miro, you know that drawing can take your brain to a different place. So it should come as no surprise that in the contemporary fine art world, drawing is all about process. The idea is that unlike painting and sculpture, the immediacy of drawing allows artists to explore concepts and ideas without the obligation to create a finished or independent object. Meanwhile, doodling at work is undergoing a renaissance. It’s said to improve memory and help formulate solutions that can’t be easily put into words (in case anybody from my office is reading).

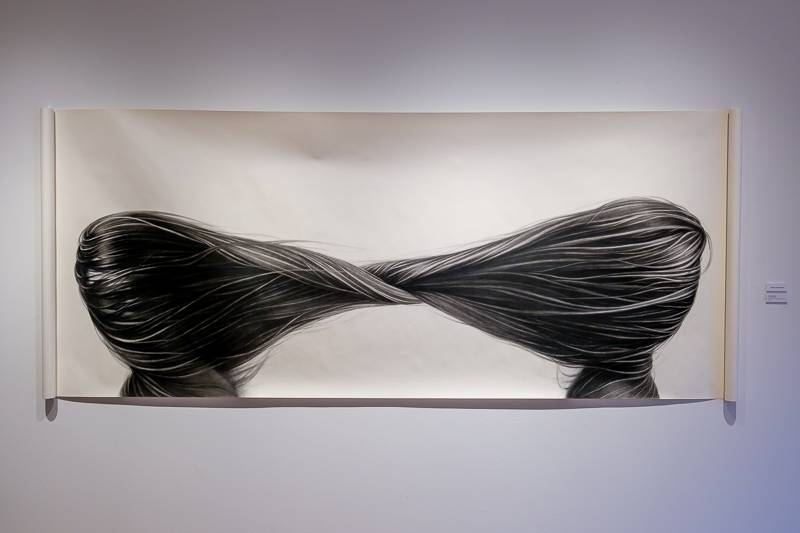

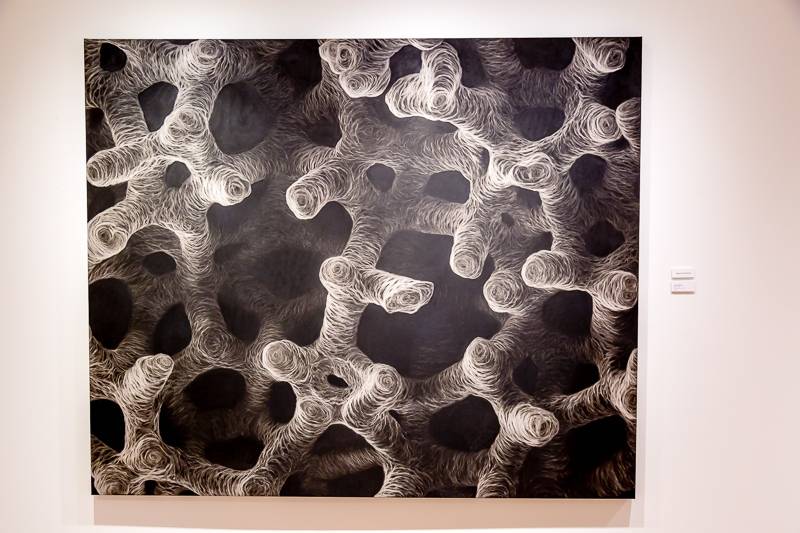

With 2016 State of the Art: Drawing Invitational at Parkland College’s Giertz gallery, Shelby Shadwell has curated a drawing exhibition that challenges “drawing as process.” Shadwell, who teaches in the Art Department at the University of Wyoming, wanted to “bring together artists who exhibited drawings as finished products that could be considered on par with more traditionally valued paintings.” The seven artists featured explore some interrelated themes — biological forms and the body, and micro and macro landscapes being a few. But the one thing (apart from the use of charcoal, Shadwell’s preferred medium) that unites the drawings is technical mastery. Standing in front of Hong Chun Zhang’s “Twin Spirits #3,” done on a 42” x 100” piece of paper with scrolls, it’s difficult to deny that drawing can be really, really cool.

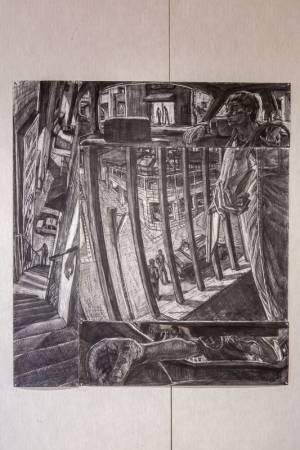

An exhibition catalog is available for $5. The Giertz gallery is small and cozy. Reading the artist’s statements, I discovered that while process may not be the focus of this exhibit, it’s certainly still there. Christopher Troutman describes starting with lines and shapes, which suggest figures and environment, which eventually imply narrative and the passage of time. Philip Michael Hook describes entering into a mental space in the studio that the painter Squeak Carnwath calls “Subterranean.” Even the drawings that are more representational — like Tamie Beldue’s ghostly portraits or Jeremy Plunkett’s mysterious mezzotints of plastic bags — have a  dreamlike quality. I would guess that what separates these drawings from more “process-focused” ones is a kind of fidelity to the interior life: a willingness to stay with an image and make it more real through refinement and detail. Overall, it’s a wonderful exhibit. My only gripe was that a couple of the artists seemed to have submitted prints rather than originals, since I loved seeing the texture of the materials.

dreamlike quality. I would guess that what separates these drawings from more “process-focused” ones is a kind of fidelity to the interior life: a willingness to stay with an image and make it more real through refinement and detail. Overall, it’s a wonderful exhibit. My only gripe was that a couple of the artists seemed to have submitted prints rather than originals, since I loved seeing the texture of the materials.

I talked with Shadwell to find out more about what went into curating the exhibit and his thoughts on the state of drawing.

SP: What is your connection to Parkland?

Shadwell: I was invited to be in a drawing show called Defining Territories: Contemporary Drawings in 2013. There were four artists total, and it was curated by two of the faculty: Joan Stoltz and Matthew Waltt. They had seen my work on the cover of a publication I was in, International Drawing Annual no. 6. I did a public drawing demonstration as part of the show. And then I met Patrick Hammie by chance. I really enjoyed his drawings, so I had him out to the University of Wyoming as a visiting artist. Then last spring I was part of the 8 to CREATE show in Champaign-Urbana. Because I was in that, Lisa Costello, the curator/director, invited me to curate the drawing invitational. It’s the first time I’ve curated a drawing show, and it’s something I’ve always wanted to do. The field of drawing doesn’t get a tremendous amount of credit, so it’s a real honor to participate in this.

SP: What does “invitational” mean?

Shadwell: Basically, Lisa invites me to guest-curate. Then I invite other artists to the show based on what I’ve seen of their work. They’re free to work with Lisa to do whatever makes sense for the show. They have various schedules; they may have things that are already lined up or they don’t have time to participate. Most of the artist I wanted to have in the show were able to participate. Joseph Crone and Erin Fostel were the two who didn’t make it in.

SP: I was interested to read in your curator’s statement that drawing has historically been thought of as a process for planning rather than an end in itself. Can you tell me more about that?

Shadwell: It’s not a set-in-stone kind of thing, but when you look at the history of art and how art has developed, drawing was not seen as an end in and of itself. This spans way back before the Renaissance, and really up until you get into modernism with Manet and the impressionists. A lot of times drawing was very much for planning: a painting or a sculpture lasts for ever, but drawings will fade to some extent. What was seen as being more important was this really refined finished product whereas the roughness and looseness of drawing was a means to an end.

But that has changed rapidly through the last century. There’s a famous photo of Picasso where he has drawn with a light stick and the exposure is in front of him. A lot of drawing machines are popular in the field of drawing. Writing as drawing. All of these methods are process-based, where the product is not important in the least. Richard Long basically walked a line in a grass field and that was “drawing a line through walking.” That’s ephemeral, it goes away.

I’ve seen so much emphasis in drawing swing away from the idea of a finished product, and that was the reason I chose the artists I chose. It’s also part of my own practice. We create these objects that could stand up to any painting or sculpture. I’m trying to cut against the grain by presenting these works as products that can be really jaw dropping just on the face of them.

SP: How did you choose these particular artists?

Shadwell: I know some of them, and some of them I’ve never met. I’ve seen their work in person or in print somewhere. I also think I found out about a lot of these artists through the International Drawing Annual, which is a publication of the Manifest Creative Research Gallery and Drawing Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

I don’t necessarily have a great deal of knowledge about what’s behind their work. What does link them all together is a sense of kinship. A lot of times drawers and painters are off in our studios by ourselves and we get a little bit isolated from each other. The great thing about this show is that when I look at their work — Chris Troutman and Chris Ganz, for example — I look at the marks they’ve made, and I think “I’ve been there, I’ve made marks like that.” I can tell if they’re right or left handed from the marks that they make.

SP: You said that drawing doesn’t get a lot of attention. Is it a popular focus for artists?

Shadwell: Yes, I’m an arts educator as well and I teach all levels of drawing at the University of Wyoming. For every artist, no matter who they are, drawing is the one thing that links all artists together to some extent. Everybody learns the fundamentals of drawing. Some people enjoy it more than others. I find that there are more artists who are specializing in making drawings, but it’s still smaller than the number of artists who are doing painting and drawings or sculpture and drawings.

SP: Do you have any advice for a beginning drawer?

Shadwell: The main thing is that sometimes people equate art with magic, in that it’s different from every other activity that we do as human beings. In order to improve in basketball I could shoot ten free-throws and I’ll miss half of them. When people fail at art, they say “I guess it’s magic, I can’t do it.’ What people don’t know is that you have to do ten more drawings, and ten more, and ten more, etc. People in visual art give up before they’ve done enough. My biggest advice is just to do more and more. My website only has 20% or 30% of the work I’ve made in my life.

SP: Another part of the curator’s statement I thought was interesting is that you say good art inspires a sense of “awe.” Can you expand on that?

Shadwell: I am always striving to give a coherent definition of art. I think it becomes more difficult to answer over time. As soon as someone says “this cannot be art” somebody comes along and says “oh yes it can.” My working definition right now is images or objects or entities that do invoke a sense of awe or wonder in a viewer. That can be on a couple of different levels. You get that when you look at Hong’s work in the show, because it is such an expertly crafted drawing. I also get the sense of awe from its strangeness. Before I curated this show, I watched the series “Stranger Things.” I think I actually purposefully tried to put the phrase “stranger things” in my curatorial essay, because that show was on my mind. I stuck it in as an easter egg for myself. But I can also get this sense of awe and wonder from a Rothko painting or an Elsworth Kelly painting. Or I can look at a really strong work of conceptual work and say ‘whoah, that is really blowing my mind.”

SP: What was your favorite part about curating a show?

Shadwell: When I saw the show I was like, “this show is freaking awesome” but then at the same time I felt this sense of “Oh my goodness, am I tooting my own horn too much?” So I feel like the show on the whole is awesome, and I feel like the greatest thing is that the artists chose to participate.

2016 State of the Art: Drawing Invitational is available at the Giertz Gallery until February 4, 2017. Hong Chun Zhang will be the featured artist at 8 to CREATE in March 2017.

All images by Scott Wells…

Scott is a U.S. Navy veteran and a graduate of the University of Illinois. He has been a photographer and writer for Smile Politely since March of 2015.

All images by Scott Wells…

All images by Scott Wells…