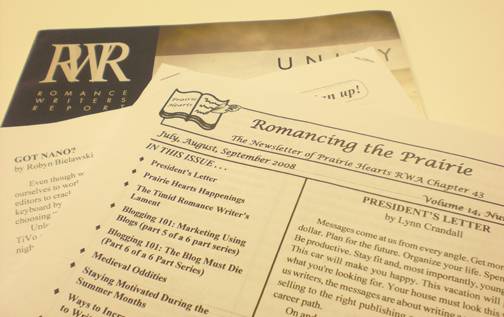

The setting — a bare conference room in the Urbana Free Library — isn’t romantic, but the topic of the meeting is: the art and business of authoring romance novels. It’s a Saturday afternoon, and four middle-aged women have gathered to talk about their writing. A copy of the latest journal from Romance Writers of America is passed around the table. The discussion surrounds a slick advertisement for an especially sultry new book, an example of how the romance genre continues to push the boundaries of eroticism.

“My son saw this,” says member Nancy Purdy, “and asked, ‘Is that what you write, mom?’

” ‘No,’ I told him.

” ‘Well, maybe you should if that’s what’s selling,’ he told me.”

This gets a laugh from the ladies. The Prairie Hearts writing group was founded in 1989 by local writer HiDee Ekstrom, who saw the need for an organization of similarly focused people. Since then, the group has become a registered local chapter of Romance Writers of America. The local chapter maintains a core membership of writers — some published, others working toward that goal — who “support each other through the thick and thin of publication.” Relationships between some members date back twenty years.

HiDee Ekstrom, left, talks shop with Lynn Crandall.

Prairie Hearts is currently composed of all women, although there have been men involved in the past. Romance writers are primarily female, but some male writers will publish under pseudonyms. Many Prairie Hearts members come from language-related occupations. Purdy, for instance, has worked as both a journalist and English teacher. But there are others, such as Ramona Burns, a maintenance foreman for the university, whose day jobs have nothing to do with the written word.

Regardless of profession, romance writers often share one trait: a need for peer support. The genre doesn’t lend itself to respect. The term “bodice-rippers,” inspired by the lurid covers of romance novels published in the 1970s, has come to embody what many critics interpret to be the genre’s stereotypical literary downfall: a tired plot where helpless heroines are attended to by macho males.

Regardless of profession, romance writers often share one trait: a need for peer support. The genre doesn’t lend itself to respect. The term “bodice-rippers,” inspired by the lurid covers of romance novels published in the 1970s, has come to embody what many critics interpret to be the genre’s stereotypical literary downfall: a tired plot where helpless heroines are attended to by macho males.

“It doesn’t bother me or offend me to read that kind of stuff,” Purdy says of the critical disdain for the genre, “but I don’t seek it out.”

Samuel Richardson pioneered the genre with his 1740 novel Pamela, which focused on courtship and featured the shocking concept of a female protagonist. Jane Austen advanced the genre with Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility, among many other classics. The modern romance genre exploded in 1972 with the publication of the bestselling The Flame and the Flower, by Kathleen Woodiwiss. In 2004, an astounding 55% of all paperback books sold in North America were romances, so the mass public has clearly overruled the critics in defining the popularity of the genre.

Prairie Hearts writers seem unfazed by negative reactions to their work. “I’ve had people make fun of it,” says Ekstrom, as others nod in agreement. “And there are certain people I just won’t discuss it with. But I love doing it and I’m going to do it whether they like it or not.”

Everyone cheerily agrees.

CRAFTING ROMANCE

The assembled quartet begins work on an exercise. Prior to the meeting, each person has been asked to write the first few hundred words of a new novel. These selections may not evolve into something bigger, but they serve to stimulate the creative juices as well as the conversation. Purdy’s offering is set during a U.S. war against the Tripoli pirates in the early 1800s.

“It’s topical,” explains Purdy upon reading her work aloud. “People will be able to relate to it because of our current war in the Middle East.”

“That’s a good idea,” replies another writer, “but how are [the woman and the man] going to meet if he’s out on a boat fighting?”

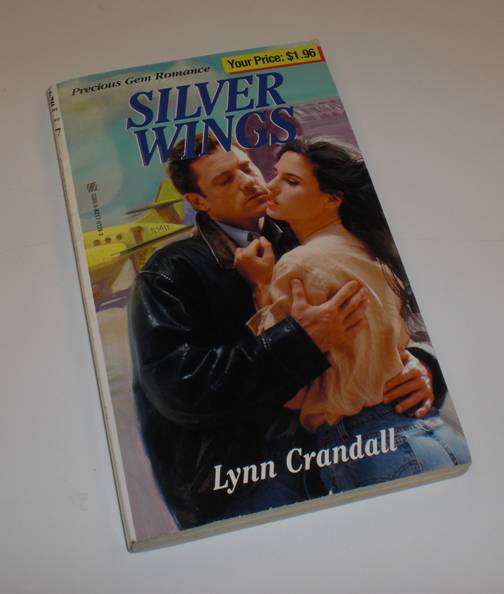

The romance genre has changed with the times. In the 1980s, publishers began to realize that the largely female demographic wanted more independent heroines. Romance writers now must create complex, strong heroines. Prairie Hearts chapter president Lynn Crandall provided an example of this shift with her 1998 novel Silver Wings, which features a protagonist who is both a successful businesswoman and an experienced pilot. As Burns puts it, “Today the woman doesn’t need the man; she chooses the man.”

The romance genre has changed with the times. In the 1980s, publishers began to realize that the largely female demographic wanted more independent heroines. Romance writers now must create complex, strong heroines. Prairie Hearts chapter president Lynn Crandall provided an example of this shift with her 1998 novel Silver Wings, which features a protagonist who is both a successful businesswoman and an experienced pilot. As Burns puts it, “Today the woman doesn’t need the man; she chooses the man.”

Writing a romance novel, as with any novel, involves a certain amount of craftsmanship, but also guidance. According to Purdy, there are, in fact, formulas available for writing such a work. For instance, in a historical romance, “it’s supposed to be 20% history and 80% romance,” says Purdy. Moreover, in all romances, Ekstrom says that “readers come to the books with certain expectations, and you have got to fulfill those expectations. There has to be a happy ending. You want to see characters grow. There has to be a conflict, both internal and external. From the sweet to the erotic, there are certain things the reader expects out of that book.”

Still, Prairie Hearts writers feel that there’s more to creating a quality romance than just adhering to the recipe. There are some things that can’t be faked. “I’m looking for the heart and soul of the author coming through in the pages,” states Ekstrom. “I can’t just look at the guidelines and then write that exact book, because my heart’s not in it,” offers another. One of the women cites Kathleen Turner’s character, a romance novelist, in the film Romancing the Stone. In one scene, Turner’s character sobs upon completing the writing of her novel. This example is held up as the image of a true romance writer.

There’s no sobbing or histrionics at the meeting, though. Members earnestly discuss a plot scenario from Crandall where a mysterious, handsome, male being — a sort of non-human, underwater-dwelling figure — emerges from the sea to encounter a stunning female diver on the beach. Will publishers see this as a paranormal scenario? A science-fiction story line? The members debate the topic matter-of-factly.

According to the Romance Writers of America, a romance has to have a happy ending and a core theme of a romantic relationship between two protagonists. Within these general criteria, there is room for many subcategories. In recent years, science fiction, paranormal, erotic, suspense and Christian-themed romances have flourished alongside more traditional historical and contemporary offerings.

Each subcategory, the writers claim, comes with its own challenges. If you are writing historical romances, for instance, you had better not have two characters meet on a railroad car before commercial railways actually existed, or readers — many of whom often choose particular romances based upon a preference for a certain historical era — will call you on it. Then there are challenges that all romance writers face, regardless of niche. Since romances aren’t exactly “required reading,” Ekstrom says, “People want to be locked into the book. It’s got to be a page turner or it’s going to be put down.” Another writer adds, “You have to have that hook at the beginning and end of each chapter.”

The sex, of course, can serve as the glue. As public standards have changed over the years, romance novels have grown steamier. Throughout the 1970s, sex was often dealt with through euphemisms, and heroines (but not their male counterparts) were often required to be virgins at the start of a book. However, publishers in the romance industry realized that books with more explicit themes began outselling those without, and changed their approach accordingly. Today, erotic romance is a thriving subcategory of the genre, but according to Purdy, there’s more to a good romance novel than the sex scenes. “Physical passion is part of life, but for me it’s all about people,” she says.

THE BUSINESS OF ROMANCE

The group places some emphasis on attempting to get their works published. The printed agenda for the day’s meeting includes a session on sharing information on the market. However, many members of Prairie Hearts were naturally drawn to the act of writing first, so finding a publisher for their work is a secondary goal. The only published author in attendance at today’s meeting is Crandall, whose lone published novel has been translated into other languages for international distribution.

The group places some emphasis on attempting to get their works published. The printed agenda for the day’s meeting includes a session on sharing information on the market. However, many members of Prairie Hearts were naturally drawn to the act of writing first, so finding a publisher for their work is a secondary goal. The only published author in attendance at today’s meeting is Crandall, whose lone published novel has been translated into other languages for international distribution.

Most members of the group have been avid romance readers for years. As in many writing groups, the members can be critical of their published contemporaries. “It’s true that there’s a lot of bad romances out there,” states Burns. “But, on the whole, there are more good than bad.”

One member mentions that, because some authors aren’t skilled at writing erotic scenes, publishers outsource such sections of the book. “They hire writers to add that stuff in,” she explains.

“They hire them?” another asks.

“Yeah, they’re like ghostwriters for sex scenes.”

The group seems both amused and disgruntled by this revelation.

According to the members, electronic publishers are helping advance the genre and are leading to more freedom of expression. “Some of the new electronic presses aren’t as strict in their guidelines as the print publishers are. There are a lot of people’s books that don’t fit the print categories,” explains one writer.

However, the four women present agree that a traditional, portable, romance paperback has a charm that newer e-pub technologies haven’t quite replaced. For a genre that requires its writers to know their history, some things never change.

——

Prairie Hearts welcomes newcomers. The next group meeting is on, appropriately enough, February 14, at the Urbana Free Library’s downstairs conference room.