For many, zine-making is completely unexplored territory; for others, it is a hobby. But for enthusiasts like Dr. Spencer Keralis, zine-making is a tradition with benefits that will last a lifetime.

As a guest artist at one of the events incorporated into this year’s Small Press Fest, Keralis- a book historian, scholar, artist, and experienced zine-maker, shared their own perspective on what zines are and what they can bring to our communities. In fact, Keralis shared with me that their own journey into the world of zine-making began as a way to find community.

“I am a child of the 80s… we didn’t have internet, we didn’t have Tumblr or Facebook, so you’d go to your local coffeeshop and see what zines were out on the little table by the door,” they recall. “So there was this real network of correspondence.”

People utilized zines as a way to connect to specific communities that focused on their interests. Anything from music to goth culture could be found in one zine publication or another.

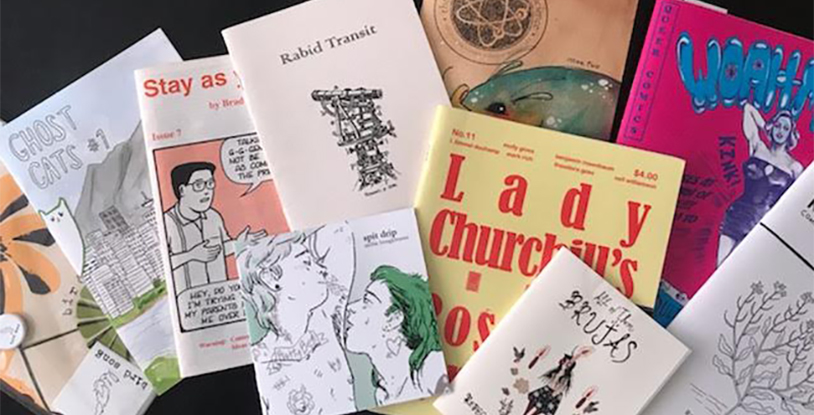

Given this massive range of subjects, there is no fixed definition of what a zine is or has to be. Everyone interprets and manifests their artistic expressions differently. According to Dr. Keralis, the best way to understand zine-making is to be handed a pile of zines and simply go from there with your own understanding of the art form. As they phrased it during Small Press Fest, “zines are essentially do-it-yourself publications. You can tell your own story to your own community in your own way. This is a sort of performative way of what new historians call ‘self fashioning’; we create ourselves through the stories that we tell.”

Even the ways that zines are made can and do vary widely. Several different methods of technology that can be utilized in the making of zines, including accordion folding, fold-and-cut bindings, hand-sewing, beadwork, silk-screen covers, and more. The only true limit to zine-making is one’s own creativity.

However, one distinct feature of zines is how we share them with our communities. Before the internet was widely available, zines were primarily distributed via coterie circulation through which people exchanged their zines with each other in relatively small groups. While this form of distribution still exists and hands-on craft making retains popularity, social media has largely transformed the way that zines continue to be spread.

On one hand, social media does facilitate desktop publishing and the dissemination of zines. However, it can also somewhat depersonalize the experience as a whole.

“Even though the internet kind of speeds up those connections, it’s also a little hard to make durable connections… You’re gonna give some random stranger your mailing address online? We just don’t do that anymore. So it makes it a little bit more challenging to share and circulate and to receive stuff,” Keralis laments.

The shift to online platforms also creates new complications regarding privacy and copyright. Some zine makers have opted for a “copyleft” approach in order to access work more easily. However, keeping some zines private can be crucial. Keralis’s research on zines related to HIV and AIDS has shown them as much, as many older zines contain sensitive medical and personal information that patients might not want publicized. Yet these limitations do not even make a dent into the wealth of zines waiting to be discovered on the worldwide web.

Despite this broadening and increasingly general audience, specific communities still manage to find connection through sharing zines. Zines that are made by queer people are often for queer audiences, Keralis explains. Even aside from this, they assert that zine culture is particularly fitting for the queer community as it is rooted in independence and rejection of typical hierarchies that censor who and what we interact with.

The roots of zine making largely coincide with queer underground comics that began to circulate widely in the 1970s, mimicking this same idea of anti-capitalism and grassroots connections. These comics grew into recognizable names such as Riot Grrl, inspiring later creations such as the Birdsong Collective and works by Anya Johanna Deniro, Kelly Link, and Archie Bongiovanni.

“So, queer zines are anti capitalist, they are punk, and they come out of this DIY tradition where you take what you need from where you can get it to produce your art,” says Keralis. “It’s something that I think has a particular appeal to queer people now because it does harken back to that moment when we were using zines to sort of build communities and share our stories because there weren’t other venues to do it.”

So if the only limit to zine-making is our own creativity, it seems like anyone can make a zine. But where do we start?

Aside from finding online tutorials for technical skill-building, Keralis emphasizes material connection as the best way to start getting involved.

“Reach out to folks whose work you admire,” Keralis suggests. Perusing zine libraries at places like the Independent Media Center can enhance a general understanding of zines as well. “Explore some of these repositories and see if there’s a style you like, or if there’s an artist you like, and then see if you can’t reach out and find them and have a conversation.”

When I first learned about zine-making, I was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of variety it encompasses. But diving deeper into the art form has revealed that it is in fact this broad allowance for personal interpretation and community-building which makes it so special. If queerness doesn’t fit right into that framework, I don’t know what does.