It is always a good idea to follow directions. Until it isn’t.

When I was offered the opportunity to interview Brian Evenson, I jumped. After I called him and conducted a forty minute phone interview, I went back and read Caleb’s assignment…which directed me to email the questions. Oops. What follows is the transcript of a pretty wonderful Saturday afternoon talk with the Sere-Seer himself, Mr. Brian Evenson. If you haven’t heard of Altmann’s Tongue, Last Days, Fugue State, or Immoblity, check your head. Which is to say, it is about damn time you did.

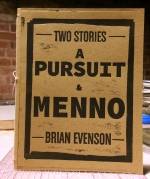

SP: I hear you have a chapbook coming out from Spork Press for the Pygmalion Lit Fest?

SP: I hear you have a chapbook coming out from Spork Press for the Pygmalion Lit Fest?

Brian Evenson: Yes! A Pursuit. [Very limited quantities] will be published in conjunction with the festival. Spork is a small press that I like very much. They have a unique quality in that they are very good at publishing poetry and fiction in an innovative way – they purposefully stray a little off the beaten track. I also admire their distinctive aesthetic – I mean, I love their book covers. Colin Winnette’s book of prose published by them is a great  example. They occupy a great space, a kind of look in-between the wide eyed big project and a small press project. They are a great fit. Also, part of it was originally published in the Ninth Letter.

example. They occupy a great space, a kind of look in-between the wide eyed big project and a small press project. They are a great fit. Also, part of it was originally published in the Ninth Letter.

SP: (That was a University of Illinois shout-out, for all you readers in cyberspace) Your work has been described as literary minimalism, horror, detective noir, New Weird, science fiction, and a whole slew of other identifiers. You are considered more of a genre writer than a literary writer. How would you describe it and yourself?

BE: A genre writer? I wouldn’t describe myself overall as that way. Immobility, [although it] ended up being published by TOR, a literary press made overtures for it first. We went with TOR for various reasons. What I think of as sci-fi or horror or New Weird — I like that term, by the way — a lot of these terms have to do with people’s nerves. Again, I like the term New Weird, that works for me, I was in Jeff Vandermeer’s anthology. I like the attempt to create a bridge between people who think of themselves as literary writers and writers who think of themselves as sci-fi, or genre, writers. There used to be a critical line or a fence between them and now I feel it is more permeable, a row of hedges that you can pass through if you want to. It is a good thing. I think that literary and genre writers have the potential to recharge one another. I really started thinking about this in 2002, when one of my books got nominated for an International Horror Guild award and I wondered: Why? It turned out that what I thought was horror simply wasn’t. When I looked deeper I realized that the best writers in genre operate with a level of sophistication in line with writers in literary fiction. They’re just terms that people use. I myself want to do the legwork so that my work is as good as it possibly can be. Peter Straub employed a special issue of Conjunctions [called] New Wave Fabulists to make this point—in which he took a number of “genre” writers and published them in this high brow literary magazine—and it provoked some thought, some discussion. It is important to see writing as a continuity, not as a series of options.

SP: Are people freaked out about how nice you are?

SP: Are people freaked out about how nice you are?

BE: People are often surprised when they meet me. I occasionally hear people talking about me within earshot. They say, “I can’t believe he’s so nice!” and I think they are surprised I am a happy guy. I have a friend who is a writer, who had the most miserable life experiences you could imagine – and only wrote stories that were really happy and optimistic and everything worked out by the end. I have had a really great, full life and a lot of support along the way, so I can stand and experiment with things that are not comfortable for some. Indirectly or directly dealing with difficult, challenging subjects is something that I enjoy doing.

SP: You will be in the middle of David Foster Wallace territory for the Lit Fest. We kind of claim him, which sounds weird but feels right. You have mentioned your admiration for his work in the past, yet you have also posited that a lot of American writers try too hard to be him. I am paraphrasing and injecting here: the real problem is that we are too in love with the sounds of our own voices. Does that sound right? You seem to want to push back creatively by utilizing simple storytelling that puts us on our heels. You have mentioned that this can be traced back to Hemingway a bit, but moreso Kafka and Beckett. Is this true?

BE: So much of the time when we think of innovative writing we talk of these huge books that are heavy lifting projects, and in American culture they can sometimes subsume innovation. I never want to be a part of that or do that. Everyone that wants to be David—and he was fantastic, I talked to him a number of times—but everyone that wants to be him simply can’t be as eloquent or complexly brilliant as he was. Not everyone has the kind of finesse that he had, so individuals that try often fail. What I have tried, what I have admired, is those works that are sparse and well defined.

SP: Any contemporaries that you admire and want to name in this style of conciseness?

BE: I like to think there are…Ben Marcus, George Saunders, Gene Wolfe, Kelly Link, Jesse Ball. Also, there’s Haruki Murakami – who appears to be solidly in the maximalist camp. But his clarity of language, his conciseness, makes him feel like more of an ally.

SP: Do you ever feel that everyone else is late to the party? Post-apocalyptic, dystopian, blasted – and yes, zombie-ridden – landscapes are everywhere on our bookshelves and screens. The populism of it makes sense now, but 20 years ago when you were starting out…?

BE: No. These are trends that simply go on. A lot of the writers who know my work, a lot of young writers who are doing work in this field, have always been drawn to it. Annhilation by Jeff Vandermeer? […] Certain things were in the air growing up in the late 70s; everyone was talking about Post-Collapse societies. Then Reagan was elected and everyone forgot about it for a bit. It is something I’ve always been interested in. I believe I am coming at it from a different angle, but I am still very interested in collapse. The end of the world party has been going on, and will be going on, for a long time.

SP: At the end of Immobility I felt bemused. Was that your intent? The loss of equilibrium (a neatly fitting conclusion) is something that your audience can try to grow accustomed to, but it is never comfortable for us, is it? Why is that? What do you want us to experience?

BE: Sometimes things end happily, but rarely does that happen in real life. The fiction I like as a reader is fiction that stays with you. I think that the books that I write do that well. I don’t want them to be forgotten. I want them to work in your head after you finish them. There’s something about leaving the readers in a slightly uncomfortable place that strikes me as a real, achievable goal. Dark humor and discomfort in my work leaves them more open to it, but it also makes them nervous about being open to it. I hope my stories are entertaining but also that they can be potentially something that can change people.

Open yourself up to the possibility of being changed by the bemusing discomfort of Brian Evenson, by attending his free Pygmalion LitFest reading at Mike & Molly’s on Saturday, 9/26 at 8:30 p.m., directly following Elena Passarello.