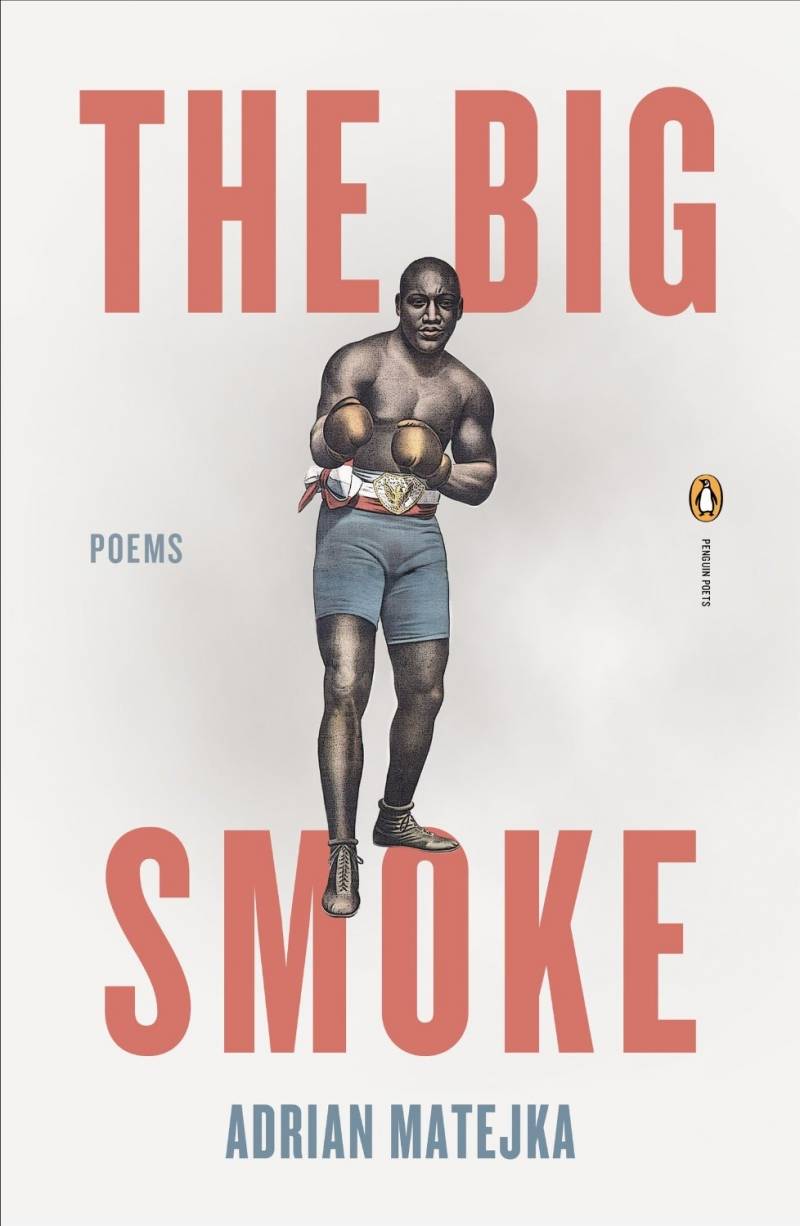

A part of me laughs after Adrian Matejka reveals his hope that someone will read his work at all. Pointing out the diminutive poetry audience and the “many, many excellent collections of poems to choose from,” he modestly speaks of his gratitude to connect with readers when they decide to pick up something he wrote. It’s a sad truth, but one that caught me off guard nonetheless — after finishing Matejka’s The Big Smoke, I was the one who felt lucky to have read the work of someone so talented, much less get the opportunity to speak with him.

Passionate, thoughtful, and unapologetically honest, Adrian Matejka is the unmissable author at this year’s Pygmalion LitFest.

Passionate, thoughtful, and unapologetically honest, Adrian Matejka is the unmissable author at this year’s Pygmalion LitFest.

His words on the power of poetry, race relations in America, and the challenges of historical reclamation are too thought-provoking for me to condense his answers any further. But I am over my word limit, so in lieu of my own praise for him, I’ll let Matejka continue the conversation.

Smile Politely: How has writing affected you? What are your personal reasons for writing?

Matejka: I think of writing poetry as an opportunity to bracket experience and share it in a concentrated, framed space. It’s a way to communicate episodes or aphorisms that are too slippery or intense for traditional grammar and cadence. Sometimes there’s a historical catalyst as in the Jack Johnson project. But more often than not, my poems lend more contemporary, immediate experiences. My new book is called Collectable Blacks and it gets into a pretty diverse range of things like identity politics, break dancing, urban migration, Sun Ra, and the Cassini Solstice Mission.

Poetry has increasingly become one of my tools for negotiating the world outside of artistic expression. If I didn’t write poetry, I’m not sure how I would have handled 2014. Or 2015 for that matter. There is so much violence, so much aggression and bias around us. I mean, the hatred toward ___________ (insert any marginalized group here) was always there, but my things-are-getting-better sunglasses got stomped repeatedly the past few years. It’s overwhelming really.

Poetry — whether I’m writing it or reading someone else’s work — is one of the main ways I contextualize it all. It’s how I protest the murders of unarmed black men and women. It’s how I speak out against income inequality and speak up for displaced people being left to die in deserts or in oceans. These recent atrocities aren’t named in my creative work necessarily, but the act poetry helps me to push back against them with willful language.

SP: In regards to your most recently published book, did your perspective (of Jack Johnson, racial issues, America’s past and present) change while researching for and writing The Big Smoke or did it affirm already set beliefs?

Matejka: I’m not sure if writing The Big Smoke confirmed or refuted any of my previous ideas about race relations in America. If anything, I was surprised at how little some parts of those relations have changed.

To give you an example, I found several newspaper articles describing the aftermath of the Great Storm in 1900. The hysteric (and completely erroneous) descriptions of African American behavior after the storm — murder, pillaging, rape, cannibalism even — was exactly the same as the (completely erroneous) hyperbole about African American behavior in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. I mean the exact same verbs, nouns, and attributions. So in some ways, it doesn’t seem like we’ve changed that much, all the way down to our rhetoric.

One thing working on the project did confirm, though, is that Jack Johnson is a quintessentially-American figure. I knew the outlines of his biography coming into the project, but I didn’t know the specifics. Johnson came from humble beginnings and became one of the most famous people on the planet just 12 years after Plessy v. Ferguson. All the while, he dealt with a kind of Jim Crow racism that manifested itself in emotional and physical extremes. He is in many ways the embodiment of the American Dream because he willed himself to succeed when almost everyone in power was opposed to his success. It was dangerous to be black and he went after what he wanted anyway.

SP: The majority of The Big Smoke is written from the perspective of Jack Johnson, but several pieces come from other speakers. Why did you decide not only to include these voices, but also to give actual depth to these other characters as well

Matejka: I originally planned to write the project just from Jack Johnson’s perspective, but it became clear that the book would be like hearing one side of a phone conversation if I didn’t include some other voices. As fascinating and complicated as Jack Johnson is, he is only one character in his own story. Some kind of balance was necessary for narrative integrity.

There were also parts of the story that Johnson couldn’t — or wouldn’t — express that needed to be told. Early 20th century masculinity wasn’t big on outward emotion. He couldn’t show concern or weakness and still be considered a “man.” That naturally diminishes some of his honesty and limits the perspective of things.

Hattie, Belle, and Etta were the appropriate foils because of their intimate connections with Johnson. They would have seen him in most successful and unsuccessful moments, away from the crowds of admirers and haters. But they also had their own intense and wonderful personal histories that add nuance and complication to the story. Each one of the women in The Big Smoke could have been the focal point of another book.

SP: Hattie is portrayed through her letters, Belle through interviews, and Etta through broken sonnets. What is the significance of making their parts distinct from Jack Johnson’s in regards to form?

Matejka: Belle, Etta, and Hattie are always distinct from Jack Johnson in voice and narrative agenda, but sometimes their agendas overlap with each other. Especially when they are talking about the same events. In my research, I also found that two of the three women used similar diction and syntax which presented another challenge to writing monologues that could be differentiated solely by language.

Each woman deserved to have her say unencumbered by comparison, so I decided to use form as a means of giving Belle, Etta, and Hattie’s distinct environments in the book. I hoped that a reader would begin to associate the various forms with the speaker and recognize her voice simply by seeing the visual geography on the page. Like Kurosawa’s Roshomon, only in poems.

SP: What was the most challenging part of turning Jack Johnson into the speaker of these poems and representing his character though them?

Matejka: Historical reclamation is an emotionally and intellectually challenging space to work in, so the whole project was difficult. From the research to shaping the voice(s) to organizing the narratives in a way that might make sense to someone who hadn’t sent the time in Johnson’s archives that I did. Especially since I wanted to show all of the figures in the book the proper respect by staying as close to their facts as possible. I spent eight years on this project from the start of my research to its publication.

Staying true to the lives of these historical figures lead to the major challenge: writing without imposing my judgments or agendas. There were so many times I wanted to have Jack Johnson say something about racism, for example, that he wouldn’t have said. Or I wanted to have Hattie or Belle call Johnson out, which they would not have done. Or to depict Johnson as remorseful, an emotion he mostly likely would not have admitted to having.

I figured out pretty quickly that my agenda did not belong in this book. I had to get out of the way. The less I was directly involved, the more successful the poems seemed to be. So I tried to share these experiences and events without sanitizing or further dramatizing them. Belle, Etta, Hattie, and Jack Johnson’s scene is dramatic and substantial enough without my input. They are the heroes in their own stories as we all hope to be.

———

Matejka will be reading his poetry for free on Friday, September 25th from 6:30-7:30 p.m. at Krannert Center Studio Theatre (500 S. Goodwin Ave., Urbana). You can see the rest of the LitFest lineup and schedule here.

Photo credit: Michelle Litvin and Penguin Books