The third annual Art of Science exhibit will be held at indi go artist co-op between April 18 and April 21. There will be an opening reception on the 18th between 6:00 and 8:30 p.m. As in previous years, the exhibit features various images that were taken using the ultra high-tech equipment at the Institute for Genomic Biology at the U of I. While the images were all originally taken for scientific reasons, they were selected for the exhibit based on their aesthetic qualities.

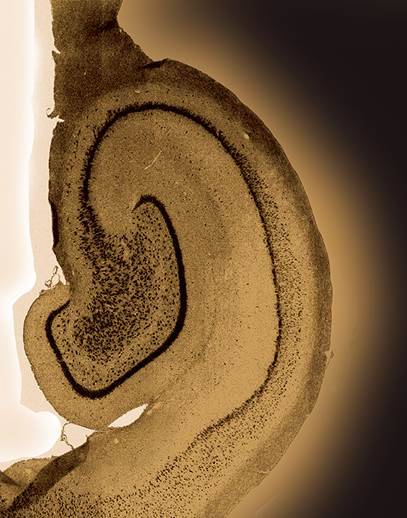

One of the images featured in the exhibit is of a section of a piglet hippocampus. It was taken for the research being done in Dr. Rodney Johnson’s lab with the Laboratory of Integrative Biology at the U of I. The researchers describe its importance in the exhibit literature as follows:

We are using the piglet as an animal model for human neonates. The region of the brain shown is the hippocampus, an area important for learning and memory. We are looking at how different factors, such as early-life infection and early-life nutrition, affect the development of the hippocampus. The broad underlying goal is to explore nutrition-based interventions that protect the developing brain from the harmful effects of inflammation.

I spoke recently with UI graduate student Matthew Conrad, one of the researchers, about the image and the studies with which it is associated.

Surprised by Results?

I asked Conrad if he was surprised by the results of the piglet animal model studies so far. He said:

We are just getting into the thick of our nutritional research. In the first study that we did, we wanted to prove to ourselves that the model we made was sensitive to nutrition and diet. So we introduced a diet that was deficient in iron – lack of iron has been linked to cognitive difficulties. What we wanted to see is: if you give a piglet a diet that is deficient in iron versus one that is sufficient, will they have learning difficulty? And what we found is that the pigs that had less iron in their diets did not do as well.

What we’re starting to get into now is looking at different compounds – to see if there’s something we can add to aid in brain and cognitive development. We are looking at certain compounds that are in breast milk that may or may not be in commercially available formula. We’re trying to see if they’re important to brain development and if they should be in commercial formula.

Why not monkeys?

I asked Conrad why the research team was trying to learn about the human brain by looking at the piglet brain. Wouldn’t it make more sense to use monkeys as an animal model since they are more similar to humans than pigs? He said:

Monkeys and other non-human primates are really one of the closest species to look at. However, the problem that a lot of researchers run into is the availability; and the restrictions, when it comes to using monkeys, are very tight. There are only certain facilities in the U.S. that are capable of housing the animals and doing research with them. The costs associated are very high in comparison to other animals. Over the last couple of years, there’s been a lot of pressure to reduce the use of primates in research.

Piglets and people

While they may not be as close of a relative to us as monkeys, there is much we can learn about ourselves from the piglet brain, according to Conrad:

A lot of my research has dealt with how the pig develops and comparing it to what is normal development in humans. Unfortunately, we don’t know a lot about what happens right around birth and about five or six years of age with humans because it’s very hard to get mothers to allow studies to be done. There have been a couple studies that have come out that focus on brain growth in the neonate, especially in populations that are at risk for developing psychiatric disorders. What we’ve found so far is that certain developmental patterns in people mirror what happens with pigs. So what we’re doing now is looking at piglets and asking what is the same and what is different than with humans.

There’s been a lot of research with people that indicates the possibility that early life inflammation or infection may have a role in later development of psychiatric disorders, especially schizophrenia. A lot of studies have been done looking at maternal infections – if the mother gets sick while she is pregnant how does that affect the fetus? There were a couple of studies done during the flu pandemic in the ‘50s that found that if the mother got sick in the second or third trimester, then the child actually had a higher chance of developing schizophrenia. So this probably isn’t the definitive cause, but a contributing factor.

What we’re interested in exploring is if the piglets get an early life infection, how that will affect the brain and what changes will occur that will predispose them to developing problems later in life.

Mazes?

One way the researchers are studying the effects of their early-life interventions on piglets is by assessing their performance in different mazes. Since the maze is such a classic symbol of animal research, I asked Conrad for his thoughts along these lines. He replied:

When we started to use the pig as an animal model for some of the research we wanted to do, we looked at things that had been used in rodent research for years and brought them back to the piglet. So we used a maze where the pig was in the center of the arena and there were eight arms. We had little doorways that had color coatings on them, and what the pig had to learn was that the milk reward was behind a certain door. That was the first maze. What we wanted to do next was create a maze that would target a more specific area of the brain, the hippocampus. So we used a spatial t-maze where a pig is in an arena and has to go either left or right. We have posters in the room, and the maze is made out of clear Plexiglas, so the piglet has to look around the room and form a map within its brain to complete the task.

Conrad also mentioned that because piglets are very smart, the mazes have to be hard enough that they wouldn’t be bored and refuse to participate.

The image itself

Conrad said of the Art of Science piglet hippocampus image itself:

This image actually came about when I was first doing a very beginning study to see if we could get a certain technique to work. We hadn’t done a technique to look for new neurons within the piglet and we wanted to see if it would work. So we brought some of our samples over to the IGB Building, and we were able to capture some images and we got some that we’re really detailed and high quality.

What that photo is showing is a really thin section of an area of the brain called the hippocampus. What we were looking at in that specific study was all the newly formed neurons within the brain region. We injected a specific drug into the piglet, and after we finish the study we can collect tissue and stain for this specific compound, which will incorporate into the DNA of any dividing cell. So what it basically gives us is a snapshot of all of the dividing cells within about a five-hour window. What we were doing with the image is looking at how many cells are dividing within that time frame.

In conclusion

I’m expecting this year’s Art of Science exhibit to be just as visually arresting and thought provoking as the previous two. While I’ve focused on just one image in the exhibit in this article, there will be many others from many different areas of science. Furthermore, it’s free.