Elephant’s Graveyard by George Brant is currently running at Parkland College under the direction of Latrelle Bright. The darker narrative follows the story of Mary the Elephant who arrives to the small town of Erwin, Tennessee with her circus. After a newbie without experience joins the circus and is handed Mary’s reigns, chaos ensues when she is distracted by a watermelon in the street, defies her under-trained handler, and kills him.

Parkland’s Second Stage was dimly lit as I walked into it this past Thursday, opening night. I was delighted to see the circular arrangement of the audience around a central stage. Aisleways cut in between sectors of audience, signifying that actors and possibly set pieces would be moving in and out between them. The colors were primary, but with a dark tinge to them. It was a bit unsettling, which set the mood for the grim play I knew I was about to witness. Excitingly, I got a seat up close and personal in the first row.

The lines were blurred where the show began. Performers came out into the audience. I prepared myself for the action. However, I quickly realized that the actors had come out to greet the audience. After I had casually chatted with several cast members, the show began with a burst of song. Easing into the show with a little bit of light-hearted chatter was retrospectively much appreciate, given how I felt after the show was over.

Elephant’s Graveyard was the definition of an ensemble piece. As an adjunct professor of Theatre at the University of Illinois and a freelance theatre maker, director Latrelle Bright is known for her devised and group-based theatre projects. In the post-show discussion, Bright shared that the playwright “gives you the lyrics of a song, but not the sheet music.” Bright’s direction has proven her yet again to be a maestro.

With the characters rarely addressing each other, the script and direction relied on alternative storytelling methods, such as shadow play. The shadows were delicate and beautiful, but also added to the overall spooky element of the show. One of the most striking of the shadow puppets was the face of Red, the newbie, who led to Mary’s downfall.

Along with shadow puppets were the clever and fluid stage pictures painted by the actors. These storytelling methods were highlighted by the simplistic, but clever scenic & properties design by Michael O’Brien and crisp lighting design by Nick Shaw. Nick Harris provided the sounds that pointedly accented the narrative. Vivian Krishnan’s costumes were cohesive but divisive, separating the players from the townsfolk.

The lines of the play read off as a poem, and the characters all functioned to tell their pieces of the overall story. I have high praise for each of the artists who were apart of this visual and verbal poetry. Among the circus players was Parker Evans as the Ringmaster, Kimmy Schofield as the Trainer, Melissa Goldman as the Ballet Girl, Lincoln Machula as the Tour Manager, Juan Suarez as the Strongman, and Zoë Dunn as the Clown. Among the people of Erwin, Tennessee were J’Lyn Hope as the Hungry Townsperson, Courtney Malcom as the Marshal, Krystal Moya as the Muddy Townsperson, Neil Ryan as the Preacher, Doug Malcom as the Steam Shovel Operator, Natalie Deptula as the Young Townsperson, and Jacob Blanchette as Ensemble. Aaron Clark as the engineer was the strong, soul voice of the railroad.

Due to the graphic nature of an elephant accident and the following hanging punishment the town bestows on Mary, my ears found this play hard to witness. When the audience learned of Mary’s fate, I saw contorted faces and tears. I would not suggest bringing children to see this show, as it is extremely upsetting in regards to violence against animals.

Playwright George Brant’s calculated discomfort served a greater purpose, which was to compare and contrast human and animal nature. Humans have made enemies of animals throughout all of known history whilst wreaking havoc on their environment. In Shakespeare’s days it was bear-baiting. Most modernly, endangered big game and unsustainable hunting.

As the Marshal chillingly boasts in Elephant’s Graveyard, “We can do whatever we want.” But why do we want to do this? The people of Erwin, Tennessee held Mary the Elephant to human standards, put her on trial, and decided her gruesome fate just to comfort themselves. Through the story of Mary the Elephant, Brant makes clear that establishing dominance over others in the animal kingdom is an atrocious practice of society, but what is more atrocious is when humans do it to one another.

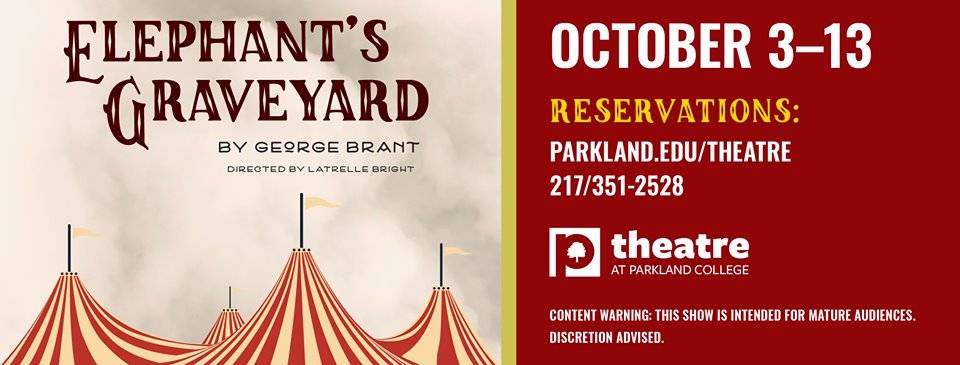

Elephant’s Graveyard

Parkland College’s Second Stage Theatre

October 3rd through 6th and 11th through 13th

203 W Park Ave., Champaign

All shows at 7:30 p.m. with the exception of October 6th and13th’s matinees at 3 p.m.

Order tickets online here.

Images courtesy of Parkland College Theatre’s Facebook page, photos by Bryan Heaton