The Illinois Natural History Survey currently has an art exhibit on display that is well worth checking out. The exhibit is called “Nature Sketches by Gladys and Ruth Dudley” and will run through the spring. It is on display in the west hallway at the Forbes Natural History Building (the building formerly known as the I-Building) at 1816 South Oak Street in Champaign.The exhibit features nature sketches by two sisters, Gladys and Ruth Dudley, who lived their entire lives in the Quincy area of western Illinois. Gladys lived from 1906 to 1994; Ruth from 1910 to 1996.

Recently, I spoke with Susan L. Post, who is a staff writer for The Illinois Steward magazine and a scientist with the Illinois Natural History Survey. She is one of the people responsible for bringing the exhibit to the Forbes Natural History Building (it is on loan from Dickson Mounds Museum) and also wrote an article about the sisters in the most recent issue of The Illinois Steward.

Recently, I spoke with Susan L. Post, who is a staff writer for The Illinois Steward magazine and a scientist with the Illinois Natural History Survey. She is one of the people responsible for bringing the exhibit to the Forbes Natural History Building (it is on loan from Dickson Mounds Museum) and also wrote an article about the sisters in the most recent issue of The Illinois Steward.

The sisters

Gladys and Ruth Dudley were born in Barry, Illinois, a small town near Quincy. As young girls, the sisters took a correspondence class in art and made the most of it. “They were born in 1906, 1910,” Post elaborated. “There was no TV. There was not a lot of stimulation. They probably took their correspondence course very seriously. And then it became their livelihood.”

After high school, the sisters started earning money as commercial artists and—among other things—created designs for advertising, textiles and wallpapers. They had their own studio and also gave lessons. They never married and lived simple lives, making their own clothes and growing much of their own food.

Their unfinished book

The sisters shared a lifelong fascination with nature and drew scenes from the western Illinois countryside. The exhibit features sketches drawn from many different decades of the sisters’ lives. Several of the sketches in the exhibit were drawn for an unpublished book the sisters began (it’s unclear if they ever finished) in the 1950s about the wildflowers in western Illinois. The purpose of the book was to urge people to save wildflowers and to show them how to raise them in their own yards. Post explained, “What these sisters were doing was actually documenting their place near Quincy.”

The sketches in the exhibit are highly realistic. Some are pencil sketches, and others are watercolors. The sisters wrote down notes which can still be seen next to many of the sketches.

After the sisters died, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources bought some sketches that remained in the sisters’ studio, but many of the drawings they made over the decades are still unaccounted for. Post said, “The question we have is… what happened to it all? Where did it all go?”

So far as can be determined, nothing was ever published, despite the years of work the sisters put into the project. Post said, “The DNR looked, but we’ve never found a book. We have a lot of Botany books here, but we can’t find any records.”

In 1982, Ruth Dudley had an exhibit of her sketches displayed at a library in Quincy. The sketches were of the wildflowers she saw blooming alongside the roadways, pastures, and wooded areas where she lived. She wrote on a panel that accompanied the exhibit: “My purpose, hopefully, is to paint them in such a way as to call attention to their beauty. Just because they are blooming where they are does not necessarily mean they are weeds.”

A paranoid vision of the future?

For the same exhibit, Ruth Dudley wrote of another motivation for painting wildflowers, the same motivation that compelled her and her sister to begin their unpublished book in the 1950s: “Another reason for painting them is to preserve, for future generations, a record of some of the beauties of nature that are all too rapidly disappearing. Many wild flowers that were common when I was a child just aren’t around anymore. They are fast falling victim to increased urbanization, increased tillage of the land and “better kept” roadways.” The sisters were worried that the wildflowers they grew up with would soon be gone.

Post said of the sisters, “They were seeing the landscape change. In the early 1900s, the prairies were being plowed; grassy areas were disappearing and woods were converted to farmland. The wildflowers are disappearing, as are the roadside patches. People were putting more and more land into cultivation. So the patches of woods and prairies where you might have seen wildflowers are no longer there.”

Post said of the sisters, “They were seeing the landscape change. In the early 1900s, the prairies were being plowed; grassy areas were disappearing and woods were converted to farmland. The wildflowers are disappearing, as are the roadside patches. People were putting more and more land into cultivation. So the patches of woods and prairies where you might have seen wildflowers are no longer there.”

From this, Post believes that the sisters thought, “We need to document this so it’s not totally lost forever.”

I asked Post if the sisters’ foreboding has turned out to be accurate. She stated that some wild flower species are, in fact, greatly reduced in Illinois and some even gone entirely from the state. Post said, noting the sisters’ sketch of a Cardinal Flower (see picture), “This Cardinal Flower is really cool—a lot of times you could see it in ditches or in wet areas. They are more spotty now.”

Post told me that the wildflowers the sisters drew probably aren’t in danger of disappearing entirely. However, she believes that there is still reason for concern; as to the sisters’ fear of total extinction, Post said, “It hasn’t come true yet, but who knows.”

Post feels that a lot of the sisters’ mindset was a product of their times. She said, “They are seeing highways being built that weren’t there when they were born. They see more and more land being paved over, and are thinking ‘Oh, we’re going to lose these things.” She reflected that if the sisters’ had begun their activism later in life they might have been less alarmed, because the state of Illinois did in fact make new steps to preserve natural areas starting in the 1970s through the Illinois Natural Areas Inventory.

“One nice thing about Illinois, at least, is beginning in the 70s, we started acquiring pieces of land that were in pristine condition, and these formed the backbone of our nature preserve systems. And Illinois has one of the finest nature preserve systems in the country. We were leaders in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Our problem now is budget cuts.”

While there were Illinois state parks in the 1950s, the nature preserve system wasn’t really going yet, according to Post. “This would have given the sisters hope, had they known about it—that there were people out there preserving land, trying to save some of these pieces of land.”

“People do not do illustrations like this anymore.”

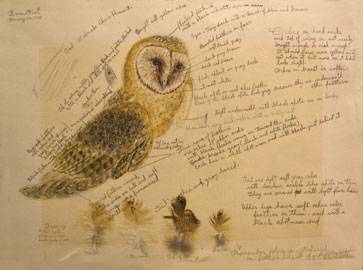

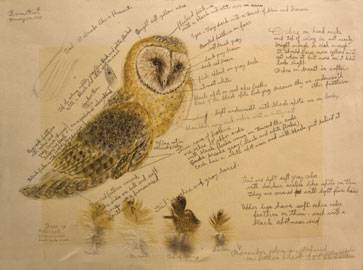

One of the more striking sketches in the exhibit is one of a barn owl (see picture). Post explained why it’s one of her personal favorites of the pictures on display: “I love this barn owl. I think because it has these feathers, maybe. These are something you don’t find all that often anymore in this state.”

One of the more striking sketches in the exhibit is one of a barn owl (see picture). Post explained why it’s one of her personal favorites of the pictures on display: “I love this barn owl. I think because it has these feathers, maybe. These are something you don’t find all that often anymore in this state.”

The Dudley sisters—as well as being interested in saving Illinois wildflowers—were interested in preserving old buildings, which (although they may not have been aware of it when the owl was drawn) actually ties in with why you see less barn owls these days than in the past. Post explained, “Most people have gotten rid of their barns. That was the roosting place, or a nesting place, for them.”

I asked Post why she feels this exhibit would interest someone from the general public and she said, “People do not do illustrations like this anymore. A lot of scientific illustration is done on a computer. The patience these women must have had to capture these illustrations is incredible. If you’re out in the field a lot, these are what these flowers look like. That’s what, to me, is inspiring about it.”

She continued that she’d like to ask the Dudley sisters: “How long did each one of these take? Did you draw from just one specimen? Did you have to sit outside and do them? Did you bring the specimen inside? How did you actually do that? Because it looks so real. For this owl, did you just sketch it in? How many times did you have to do it until it looked right?”

Post concluded: “I just hope people see it and appreciate it.”