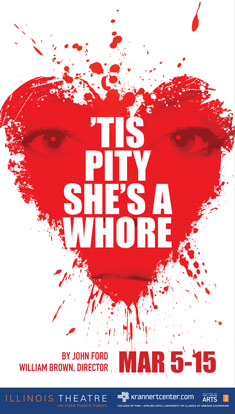

There is a moment in Hamlet, just after our conflicted prince has gone all nunnery bananapants on Ophelia, when Claudius tells Polonius and the rest of us that “Madness in great ones must not unwatch’d go.” This quote came to me more than once during last Thursday’s opening night performance of ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, a long-banned and seldom-produced 17th century play by John Ford, and for three very good reasons:

- There are plenty of parallels between Ford’s work and more than one of Shakespeare’s tragic couples.

- This play is chock-a-block with madness. Madness left and right. Everywhere madness. Buckets of it.

- This play, under the direction of Chicago director William Brown, achieves moments of true greatness.

For these reasons, and many more, this is a play that must not unwatch’d go.

The story, in a nutshell, goes something like this:

Welcome to Parma, Italy. Giovanni, the son of a prominent gentleman named Florio, has fallen desperately in love with his own sister, Annabella. Annabella, meanwhile, is being pursued by a trio of suitors: the capricious Soranzo, the callow Bergetto, and the menacing Grimaldi. Against the advice of his counselor the Friar, Giovanni confesses his love to Annabella; when she instantly requites his love, they share a passionate, incestuous night together.

Welcome to Parma, Italy. Giovanni, the son of a prominent gentleman named Florio, has fallen desperately in love with his own sister, Annabella. Annabella, meanwhile, is being pursued by a trio of suitors: the capricious Soranzo, the callow Bergetto, and the menacing Grimaldi. Against the advice of his counselor the Friar, Giovanni confesses his love to Annabella; when she instantly requites his love, they share a passionate, incestuous night together.

Meanwhile, Soranzo is pursued by Hippolita, whose love he has spurned even after she committed adultery with him against her husband Richardetto (who is now believed to be dead). After Soranzo refuses Hippolita, she engages Soranzo’s henchman Vasquez in a revenge plot against his employer.

That’s enough to get you started, though it’s important to know that Richardetto is not, in fact, dead. In fact, he has shown up under an assumed identity (as a doctor who is staying in Florio’s home), and he has engaged Grimaldi to assassinate Soranzo (who cuckolded him). This backfires spectacularly, resulting in the accidental death of Bergetto, who has just fallen in love with Richardetto’s niece after being rejected by Annabella.

From there, things get a lot messier; and by messier, boy do I ever mean bloodier.

Wait — did I mention that Annabella is pregnant? She is, as a result of her night with Giovanni. When she discovers this, she agrees to marry Soranzo on the Friar’s advice, and their wedding date is set. Following their nuptials, however, Soranzo discovers Annabella’s condition and loses his froot loops. He plans a grand revenge against Giovanni, which — while it does result in the brother’s death — also leads to a veritable orgy of blood and prolonged death spasms.

It’s true that the plot of the play, like those of Shakespeare or others of its era, can seem convoluted, but no one with a three-minute Wikipedia primer and a decent attention span needs to worry about following along. This ultra-stylized modern-dress adaptation, by director Brown, flows so briskly across the stage and so intelligently out of the mouths of its cast that one cannot help but get swept up in the emotional current.

The deceptively spartan set — designed by Yeaji Kim, with dazzling floor-to-ceiling projections by Kim and John Boesche — transitions smoothly from welcoming home to shadowy alley to posh poolside pad. And the utility of this gorgeous bronzed backdrop is augmented by smart and evocative lighting (by Lauren Tyler) and sound (by Dj Puuri). I don’t know enough about sound design to explain how the actors’ voices were made to echo only when they were in the Friar’s church; for all I know, there’s just a button marked “echo.” But however it’s done, it’s appreciated, as are the swimming pool suggested by brilliant blue light and the blood spatter images that accompany the grand (guignol) finale.

On the design side of things, respect must be paid to costume designer Kaitlyn Day for her inspiration and consistency in creating a look that is both timely and timeless. The wardrobe for this production skates along the line between trendy and over-the-top and does so with great flair. In their lavish, Jazz Age-meets-J. Crew threads, everyone looks fabulous, even when they look ridiculous.

All of this opulence would be wasted, of course, if the actors performing the play were not also worthy of praise. How fortunate, then, that the cast of ‘Tis Pity is not only uniformly good but mostly outstanding.

As the tragic lovers Giovanni and Annabella, David Monahan and Clara Byczkowski have perhaps the most difficult jobs of all, and not because they both appear fully nude — although they do, and this is handled with both grace and naturalism. In the hands of lesser actors, the siblings’ taboo love and descent into despair might seem overwrought and one-note. Giovanni has less nuance, on the page, but Monahan gives him fragile hope to go with his tormented soul. And as Annabella, Byczkowski conveys such a spark of happiness in rejecting her suitors — all too briefly confident in her love for her brother — that it is crushing when reality closes in on her.

As the tragic lovers Giovanni and Annabella, David Monahan and Clara Byczkowski have perhaps the most difficult jobs of all, and not because they both appear fully nude — although they do, and this is handled with both grace and naturalism. In the hands of lesser actors, the siblings’ taboo love and descent into despair might seem overwrought and one-note. Giovanni has less nuance, on the page, but Monahan gives him fragile hope to go with his tormented soul. And as Annabella, Byczkowski conveys such a spark of happiness in rejecting her suitors — all too briefly confident in her love for her brother — that it is crushing when reality closes in on her.

As the suitors, the audience is blessed with three very different actors with brilliantly disparate approaches.

The plum role here is, perhaps, Soranzo, who has the additional juicy Hippolita subplot. As this temperamental ladies’ man, Thom Miller delivers another in a string of great performances. Miller has great facility with physical, emotional roles, and his Soranzo has all this as well as a foppish, hair-trigger Gatsby-esque charm.

Speaking of foppish, Brandon Rivera’s performance as the cartoonishly childish Bergetto comes dangerously close to stealing the show. He is a magnetic comic performer, distinguishing himself in a fantastic cast as someone who is (in the words of the late Harris Wittels) “down to clown.”

Completing the trio is Jordan Pettis as the hulking, lethal Grimaldi. He is given less stage time and fewer lines than the others, and yet Pettis makes Grimaldi indelible. His ease with Robin McFarquhar’s fight choreography is impressive enough, but there are other, much more surprising tricks up his sleeve later in the play. (I won’t spoil it, as these are innovations of the adaptation, and not something you’d get from the 400-year-old script.)

I want to spend a paragraph on each and every member of this fine cast, but I fear that would try the patience of even the most ardent reader. I will say, in brief, that Timuchin Aker (as Florio), Wigasi Brant (as Richardetto), and Robert G. Anderson (as Bergetto’s supportive uncle) bring great wit and honor to relatively stock characters. Likewise, Sarah Ruggles brings charm and sauciness to Putana, a character that could otherwise be Juliet’s Nurse, and Allison Morse (as Hippolita) blows the roof off the theater and the cliché of the woman scorned.

And then there is Neal Moeller, whose double- and triple-crossing Spaniard, Vasquez, is as vibrant and gleeful a villain as you are likely to encounter. I hadn’t personally seen Moeller since his portrayal of Van Helsing in Illinois Theatre’s production of Dracula, and I am genuinely glad that that dry spell is over.

The adaptation of this play couldn’t be better, nor could the timing. Every once in a while, a play comes along that is perfectly, almost eerily in step with the popular culture. In this case, we’re talking about a play from the 1630s (!) that tortures and humiliates its women yet somehow manages to embrace feminism (I’m dead serious) by emphasizing the hypocrisy and pomposity of the patriarchy. Adapting a text like this for modern audiences is so much more than simply handing the actors some cell phones or putting them in leather jackets. Crafting a narrative and an aesthetic that mirrors contemporary culture while maintaining its classic voice is a tightrope walk, and William Brown crosses that wire with impressive balance. This is a play that went a couple of hundred years without being seen, and a production of this caliber makes me glad that not everybody thought they could give it a whirl. This is big-kid theatre, and this is exactly the kind of spectacle that a venue like Krannert Center does extremely well.

The only criticism I can truly level against my viewing of this play has nothing to do with the performance itself. Rather, it is with the audience that I must take exception. On the night that I attended this imaginative and engrossing work (Opening Night, no less), I was all but surrounded by people who seemed completely uninterested in being there. In other words, many of the faces I saw that night (and it was easy to see them, illuminated by the glow of their cell phones), belonged to students who attended based on a class requirement. I don’t mean to stereotype the student body of such a good school, but it was distracting and ultimately disheartening to hear so many conversations before and even during the play about leaving at intermission and “getting the rest from the internet.”

The number of people in attendance that night, just in my section of the auditorium, who could not be pried away from Instragram long enough to appreciate the work being done on stage was pretty appalling. Yes, most of them stayed until the end (before bolting for the doors DURING BOWS), and yes, I’m sure there were some who paid attention or even enjoyed the show. But, for the most part, these are people who can say they went to the theatre like someone with a two-hour layover at Hartsfield-Jackson can say they’ve “been to Atlanta.”

A modest proposal to professors: howsabout you stop requiring your students to attend these plays. I know you mean well, and I understand that there are those happy few who might experience some sort of awakening. I get it, and I can only hope, for the sake of the theatre, that they will find their way to love it on their own. In the meantime, right now, at Krannert Center…? The actors, designers, crew members, and people who actually care about theatre deserve better.

‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, a play by John Ford, will continue its run in Colwell Playhouse from Thursday, March 12th, through Sunday, March 15th. I cannot recommend this production highly enough, and I hope those with time, means, and curiosity will make plans to see it.