Linotype: The Film — In Search of the Eighth Wonder of the World plays on Thursday at Parkland Theatre. Proceeds from the event (the suggested donation is $7) will go to Parkland’s Fine and Applied Arts Department. A panel discussion will take place after the film.

Linotype: The Film — In Search of the Eighth Wonder of the World plays on Thursday at Parkland Theatre. Proceeds from the event (the suggested donation is $7) will go to Parkland’s Fine and Applied Arts Department. A panel discussion will take place after the film.

The poster for the film was designed by Molly Poganski, shop manager of the Living Letter Press in Champaign. Paul Young, a design instructor at Parkland, asked Poganski for the design.

Smile Politely had a chance to ask Director and Producer Doug Wilson a few questions about the film:

Smile Politely: When and how did you get involved with the Linotype?

Doug Wilson: I got involved with the Linotype about eight years ago when I was teaching myself letterpress printing while I was studying graphic design at Missouri State University. I visited a local print shop and he had a working Linotype. It was love at first sight.

SP: Whose idea was it to make a film about a technology that people see as outdated?

DW: It was my idea almost immediately after I first saw a running Linotype. The idea to make a film about the Linotype rattled around in my head for four or five years until I left my job and decided to make the film full time back in the summer of 2010.

SP: What types of projects have you worked on in the past?

DW: I am a graphic designer and letterpress printer by trade. This is my first film. I was naive enough to think I could make a film!

SP: What draws you to a project? What about this particular project hooked you?

DW: Telling the story of a machine that impacted the entire world, yet no one knows about it. Also, once I met the amazing people that love these machines, I knew we had something great.

SP: What did you learn from this production?

DW: I’ll tell you when I’m done! I really am too close to it to know what I have learned yet.

—

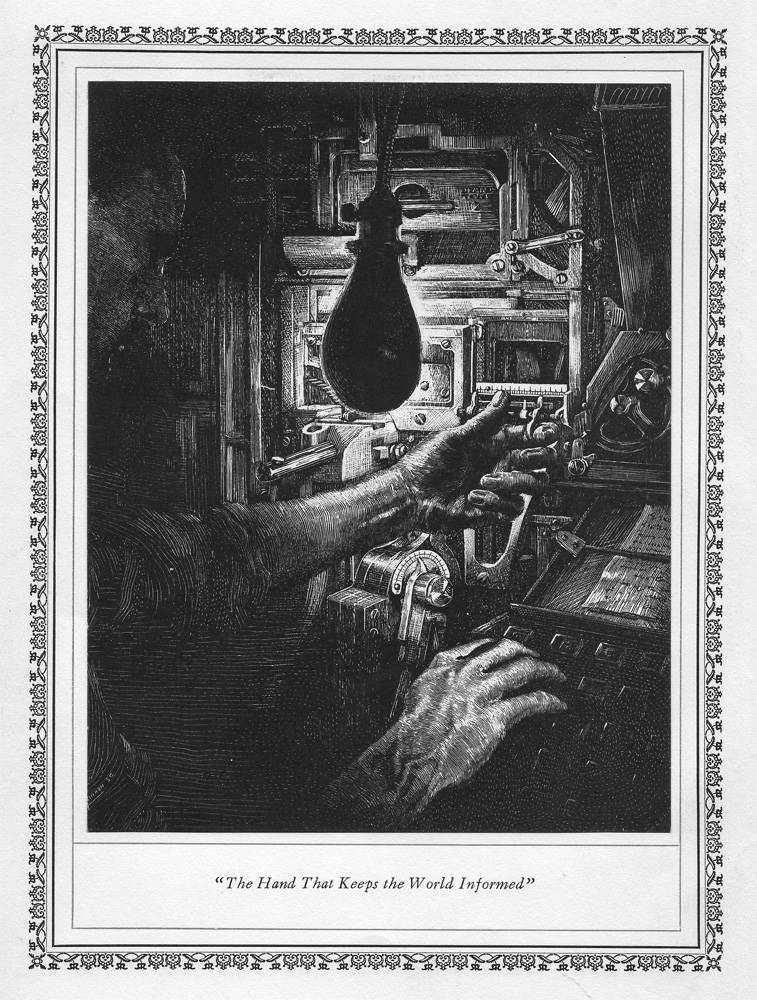

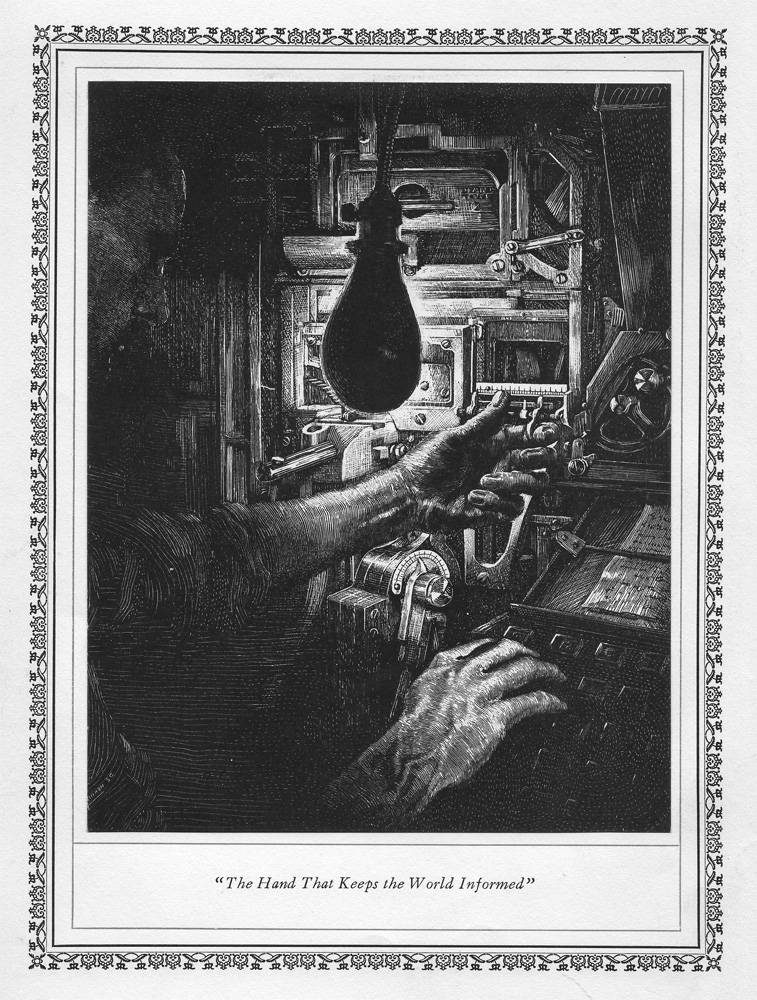

Linotype is a fascinating film about a monstrous machine. At seven feet tall and two tons, it’s described as a “cross between a typewriter, a backhoe, and a pop machine.” One man calls it the “pinnacle of Victorian engineering.” Thomas Edison called it the “eighth wonder of the world.”

A complex series of belts, pulleys, and levers put the machine in motion, its temperature reaching 550 degrees. And it’s all to create one “line o’ type” at a time.

A complex series of belts, pulleys, and levers put the machine in motion, its temperature reaching 550 degrees. And it’s all to create one “line o’ type” at a time.

One line might not seem like a lot, but the Linotype revolutionized the printing world. Workers no longer had to stack rows of type letter-by-letter, word-by-word, row-by-row. It worked at a pace six times faster. And faster printing meant a spread of information through the printed word. It transformed information and sparked literacy.

Newspapers boomed thanks to the Linotype. They began printing more editions, expanded their content, and sold at a cheaper price. In 1886, use of the Linotype began to spread rapidly and it became the supreme method of typesetting by 1928.

One of the consequences noted in the film is that, as newspapers grew, so did their headlines and their sensational stories. Everything began to move faster and the opportunity to sell grew. Publishers got people’s attention.

A series of interviews and insights in the film reveal the passion behind the connection that the operators had with their trade. Some of them are reviled by the eventual demise of the once beloved machine. Many of the machines were scrapped for metal. A few of them were bought by museums; others were taken in by Linotype University.

Wilson’s film captures all angles of the machine, from early attempts at its creation to its downfall. He seeks out repairmen, instructors, and the oldest living operators. The historical implications are evident and they are given life in the operators that once ran them. There’s a bit of sadness in the eyes of those old “hands” that look at what was once their imperative duty — to keep the world informed.