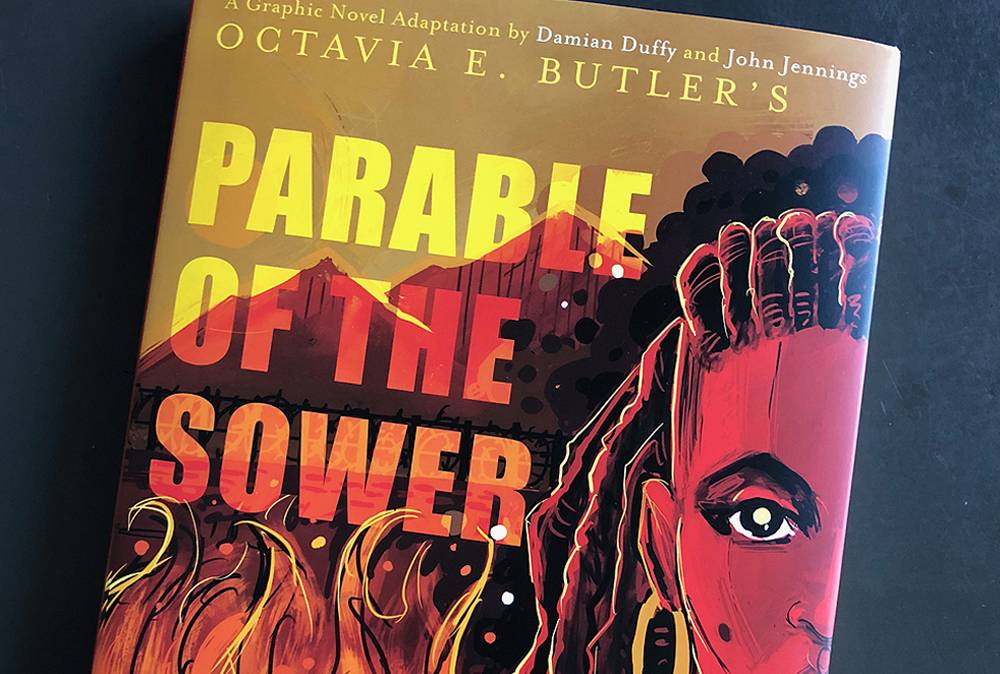

How often do you lament the way we’re living right now? Once a day? Fifty? The COVID-19 pandemic has us living in a way we didn’t think we’d have to, at least in our own lifetimes. It’s during this unusual and stressful time that I picked up the graphic novel adaptation of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower by Damian Duffy and John Jennings. Both men are graduates of and current (Duffy) and former (Jennings) professors at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Speculating about all of the terrible things that could happen, to the world or myself, is something I do often. But most of the things I imagine will never happen to me because of my privilege: as a white person, as a white woman, as someone with financial/food/housing security. It’s important to keep that in mind when reading works written by people whose experiences I don’t share, or about marginalized communities or individuals.

Octavia Butler (1947-2006) is the author of almost twenty works of speculative fiction. Speculative fiction is more or less what it sounds like: works of fiction — stories — that consider imaginary pasts and futures, realities and universes. The term has gained popularity, or at least more familiarity, in the last few decades, especially as dystopian literature has become increasingly popular in media the last 20 years. Speculative fiction is a “super genre” that encompasses many others, including fantasy, science fiction, dystopias, utopias, apocalyptic and post apocalyptic stories, and the supernatural, among others.

Butler, a black woman writing in the late 20th century, has been called the “Grand Dame” of science fiction; her influence on contemporary writers cannot be understated. I cannot state with any authority what her intentions were in writing works of speculative fiction featuring black women protagonists. I can say that as a white person, her writing encourages (white) people to learn from history and our current moments, to consider the spaces and communities we occupy, to question our actions, and try to think through the consequences. Undoubtedly, it functions differently for black readers, who may see themselves reflected in all roles in these novels.

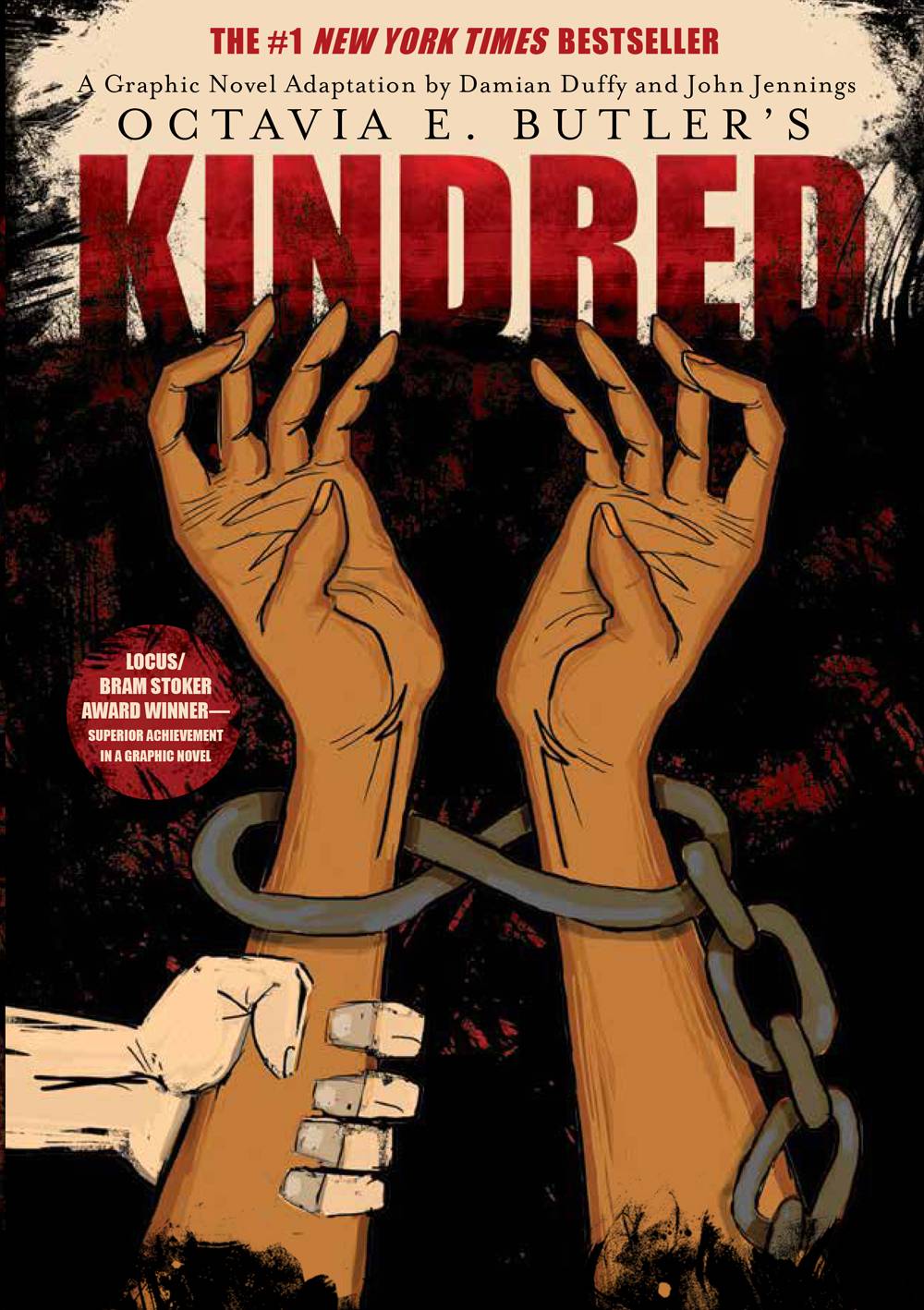

You might be most familiar with her 1979 novel Kindred, in which a black woman living in 1976 is sent through time and space to the antebellum plantation on which her ancestors were enslaved. You may also recall that just a few years ago, local author Damian Duffy and formerly local artist John Jennings adapted Kindred as a graphic novel. (You can read SP’s review here.)

Artwork by John Jennings. Image courtesy of Damian Duffy.

Duffy and Jennings have been working together for a very long time. They’ve collaborated on several graphic novels, but most recently have been adapting Butler’s Parable Series. The two-novel series begins with Parable of the Sower (1993); their adaptation was published by Abrams Books in January of this year. Parable of the Talents (1998), the second in the series, will follow soon.

I asked both men why they’re drawn to speculative fiction, fantasy, and science fiction:

John Jennings: I am drawn to speculative fiction, in general, because it gives us a certain amount of distance from a particular social issue and allows us to be more objective because it’s not the actual world. Science fiction and fantasy give us some wonderful chances, via metaphor and symbolism, to unpack what it means to be human in a complex world. It’s that narrative distance that affords us these opportunities.

Damian Duffy: The thing about fantasy and sci-fi is that they’re so often maligned as escapist, and therefore somehow frivolous. But if you think about any great escape, it’s never easy. It always requires careful observation, planning, and execution. If Harry Houdini doesn’t palm the key and slough off the straight jacket, he drowns. If Frederick Douglass doesn’t escape he is worked until he dies in bondage. What I’m getting at is there are different kinds of escapes. Escapist entertainment can be the traditional notion of something where you turn your brain off and let the predictable narrative mechanics comfort you. Or it can be about the transgressions required to escape oppression.

Parable of the Sower is set in the mid 2020s and tells the story of Lauren Oya Olamina, a 15-year old black girl with hyper-empathy living in an America that has been decimated by climate change, “environmental disasters, economic crises, social chaos.” It’s a world so violent, dangerous, and unstable that her community lives behind a gated wall in Los Angeles, but not the well-manicured kind of extreme wealth and privilege. Life within the walls is hard. There is little food, less water, and the threats of fire and attacks from pillagers. Sower takes place over three years. In that time, Lauren loses her home and her family and embarks on the treacherous journey north, toward the Pacific Northwest and Canada, where there are rumors of opportunities for a slightly better life. In speaking to the horrors Lauren encounters on her journey, Duffy says, “she finds places to put knowledge, understanding, and kindness, even in the bleakest, the most hopeless of realistic worlds.” Through all of this, she is developing her own religion called Earthseed.

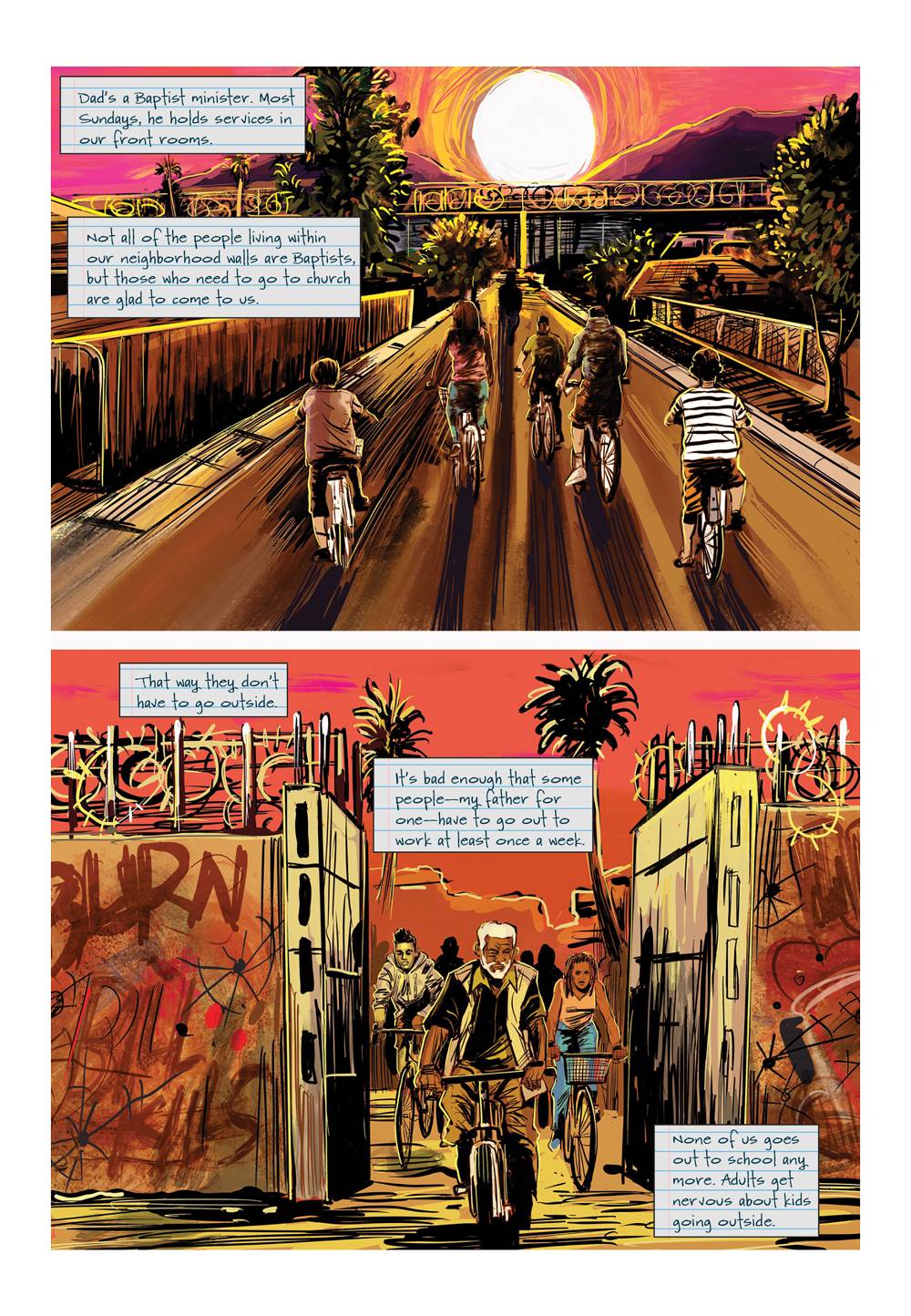

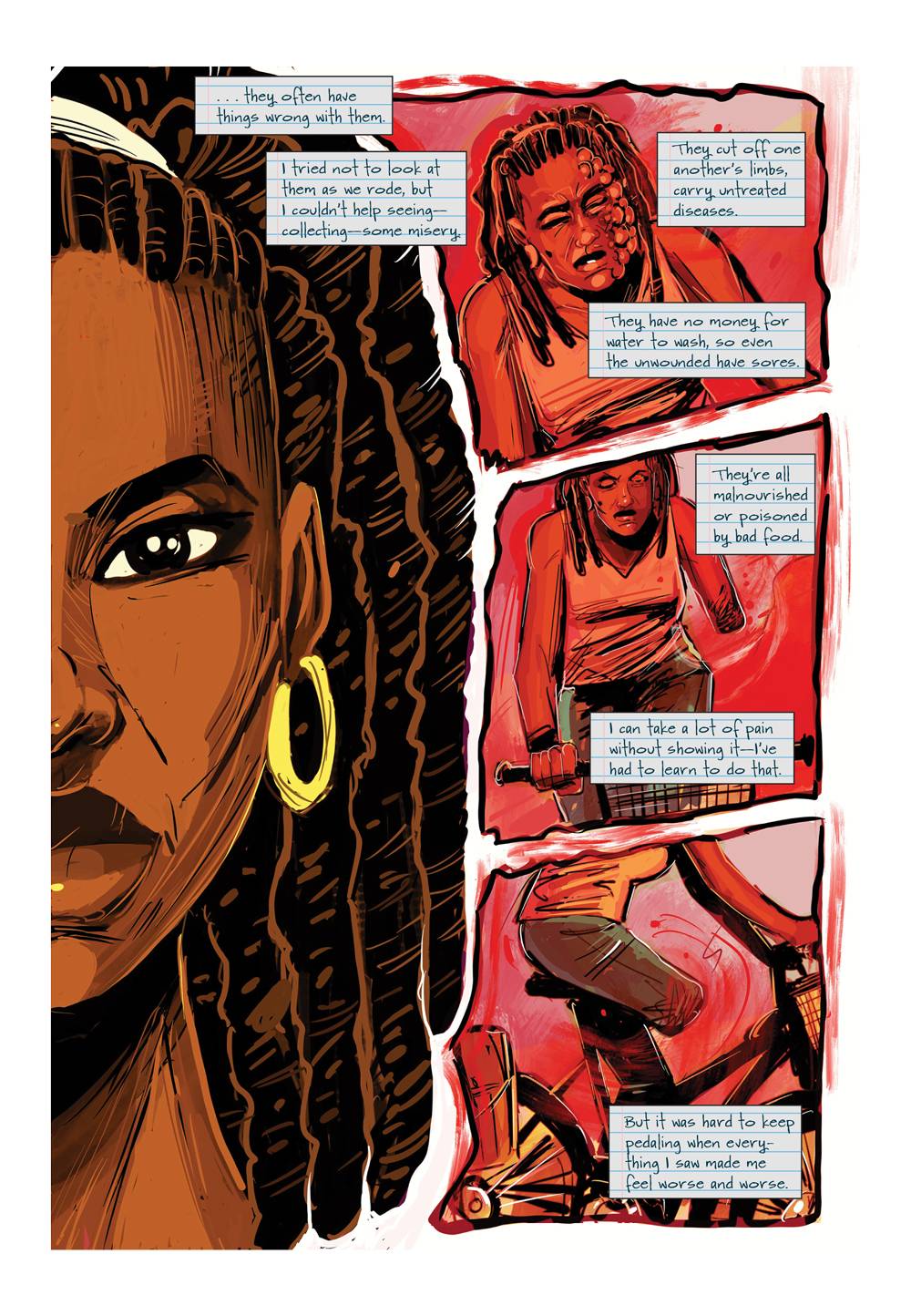

A page from Parable of the Sower. Artwork by John Jennings. Words by Damian Duffy. Image courtesy of Damian Duffy.

Allow me to note: Entire books have been written on what it means to have black women as the protagonists in fantasy and science fiction, in speculative fiction, broadly. Entire books have been written on what it means for black women to write black women. Entire books have been written on Afro-futurism, and what it means to imagine the existence and the lives of black people in the future. I don’t have the space to do that right here, and let’s be serious: I can’t hold a flame to those scholars, either. If those subjects interest you (and they should), do a little research and find more media to consume. Here’s a good starting place.

Jennings says that from Butler’s works he’s “learned a great deal about how to look at systems of power and critique them through narrative. She was a master as this.” Like the rest of her work, Parable of the Sower addresses the holy trinity of white supremacy and patriarchy — racism, classism, and sexism — and the ways these manifest in and as greed, violence, and oppression. Over the course of the novel, the reader is subtly (and not so subtly) exposed to the ways these –isms have resulted in this disastrous world, and the tolls they take on the characters therein.

Parable of the Sower was adapted by Damian Duffy with illustrations by John Jennings. Duffy’s work to adapt 300-ish pages of prose into 262-page graphic novel is no small feat; he did it well. In somewhere between 50 and 100 words per page, Duffy tells a story that is rich and dynamic through dialogue, internal monologue, and the notes from Lauren’s journals. The text is varied and interesting, but consistent in the tone. In part this is the source material, but it’s also knowing what to source material to use and how to use it. There are different visualizations of the text — that is, depending on the purpose of the text and where it’s coming from, it looks different: different typefaces and fonts. This dynamic texture creates a rhythm for your reading.

Jennings has a distinct aesthetic to his work — there’s usually no doubt the work is his. It’s unique; his imagery and formal choices are confident and consistent throughout this book. The gestures and marks are expressive, informing the pacing of the plot and the way you read the images. The attention to detail in the faces of the characters is nuanced and allows the reader to glean a deeper aspect of the emotional story.

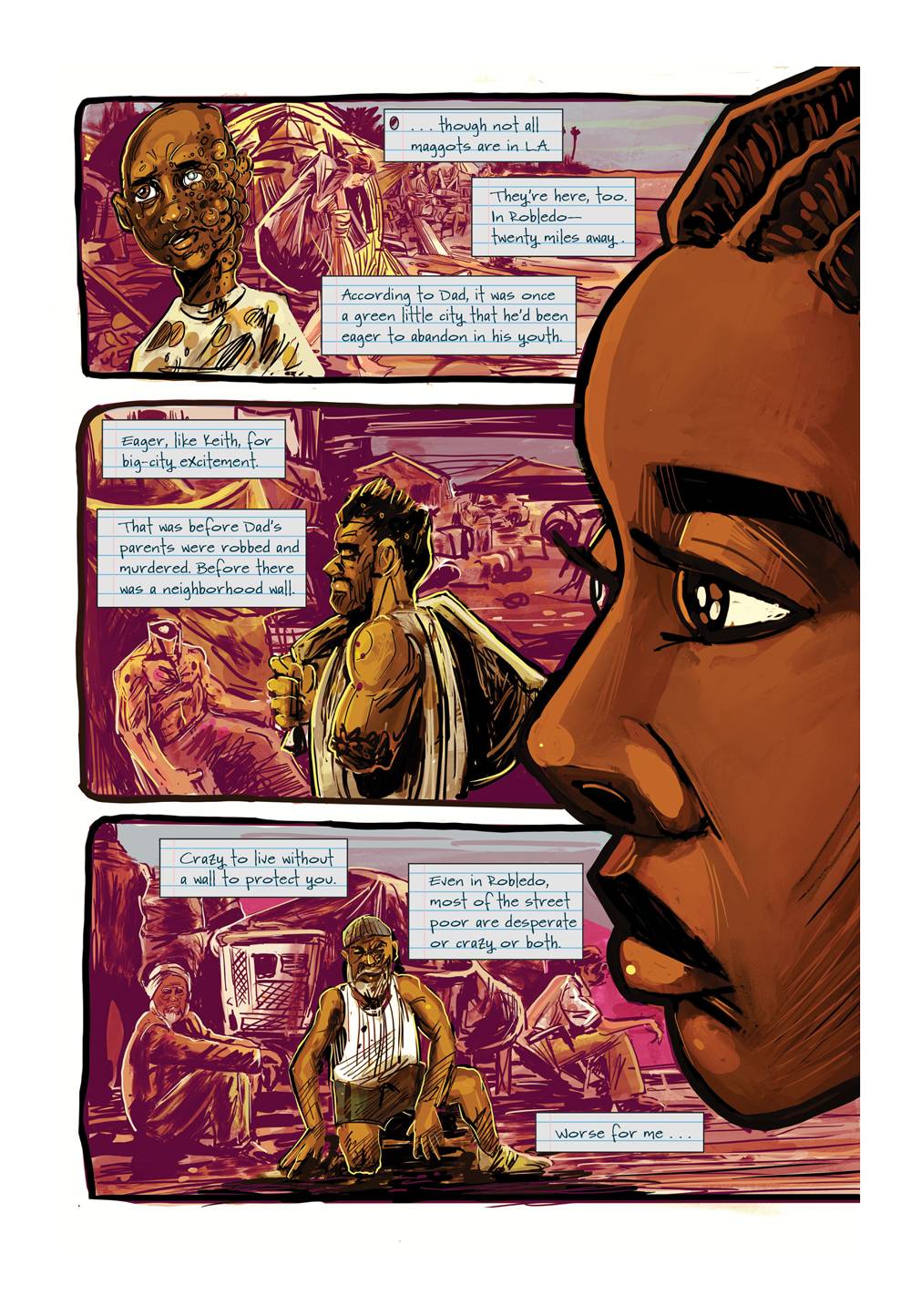

A page from Parable of the Sower. Artwork by John Jennings. Words by Damian Duffy. Image courtesy of Damian Duffy.

One the most successful things about this adaptation of Sower, and the artwork specifically, is the layout of the image panels. For the most part, no two adjacent pages share the same structure. One page might have three horizontal panels, and the next page might have six square ones, or just be one big panel. The layouts on each of the pages compliment each other, to create visually dynamic storytelling. On the rare occasion that two adjacent pages are laid out with the same number and shapes of panels, some are slightly askew. Nothing is too symmetrical. Like the variations of the text, the variations in the panel layouts provide a rhythm to the way the images are read.

Similarly, the color palette shifts with the story. Jennings’ choices tend to be monochromatic, so when there are punches of contrasting colors, it’s noticed. Those choices function as punctuation marks; they let you know you need to pay attention. It’s particularly effective when we encounter Lauren’s hyper-empathy; she experiences the pain of others, and through the artwork, we experience that pain, too.

A page from Parable of the Sower. Artwork by John Jennings. Words by Damian Duffy. Image courtesy of Damian Duffy.

When I’m reading graphic novels, I often think about drumming. I know practically nothing about music, but I know that successful drumming, on a kit with multiple drums, requires the drummer to keep more than one beat. Or maybe it’s all one beat, I don’t know…just work with me here. Drummers have the bass, the snare, and the cymbals, right? Graphic novels have to function in the same way. The text, the images, and the overall story need to work together, to create a rhythm. The reader has to be able to glean enough of the story from the individual elements to have a rough idea of what’s happening, but the beauty comes when all of those things are working together. And when they’re working together harmoniously, you probably won’t notice. That’s success. That’s this graphic novel. Duffy and Jennings have orchestrated an intense, vibrant, percussive piece.

Parable of the Sower is tragic and violent: good things do not happen to these people. Sower hasn’t exactly been a light read, but it has made some things clear. We are not (yet) living in a country with that level of sustained chaos and violence. Even though it’s fiction, it encourages me to have a little perspective, to ask myself some questions: Do I want to live in a world like that? (No, obviously.) Are there things I can be doing to help ensure we avoid a future like the one laid out by Butler? (Yes: vote, vote, vote. Agitate for change. Educate myself.) I’m left thinking about something Damian Duffy said about this book:

Parable of the Sower is quite dark. It was the first book I ever had to put down because it scared me, and that was one reason I really wanted to adapt it. But in going over it again and again, in sifting through every devastating and brutal part, you start to realize that those aren’t the point, the point is that Lauren, the protagonist, goes through all that and still keeps going. She finds places to put knowledge, understanding, and kindness, even in the bleakest, the most hopeless of realistic worlds.

Those are the things I want to keep thinking about. How can we put our knowledge, understanding, and kindness into action? We have to find a way. Learn or die, as Earthseed says.

Find Parable of the Sower at a local bookstore by searching this site.