If I told you that Julia Nucci Kelly, Director of Marketing and Communications at Krannert Art Museum, gave me the scoop on an upcoming exhibit called “Fake News and Lying Pictures,” you’d probably imagine some new media examination of Trump-era memes and Photoshop fails. You might also be shocked to learn that the prints in questions, curated by KAM curator, Maureen Warren, come from the Dutch Golden Era, and, in some cases, date back to the 1660s.

As Kelly rightly observes, Warren is “arguing that using images to persuade, even if you’re telling lies, is an old trick. Centuries old. As old as politics.” This extremely relevant endeavor offers multiple points of entry for students of art, political history and discourse, and for all consumers of political media and messaging.

While the Dutch Golden Age, roughly 1500 through 1800, may be best known for producing masterpieces by Rembrandt and Vermeer, it was also a politically fraught period, one that produced some of the earliest examples of political printmaking. And thanks to Warren, KAM has aquired the largest museum collection of early modern Dutch prints outside of Europe. In the past year, over 100 Dutch prints have been added to KAM’s already substantial print collection.

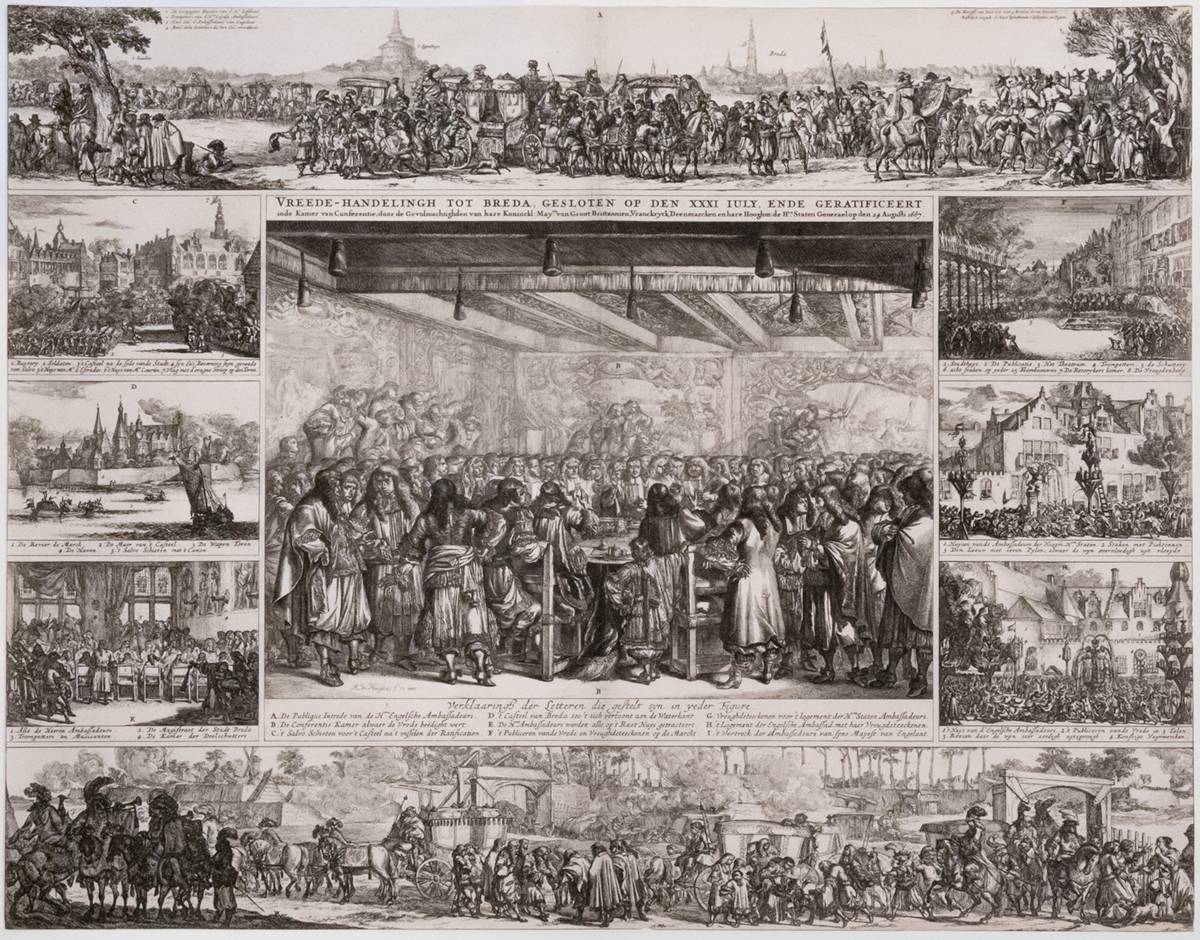

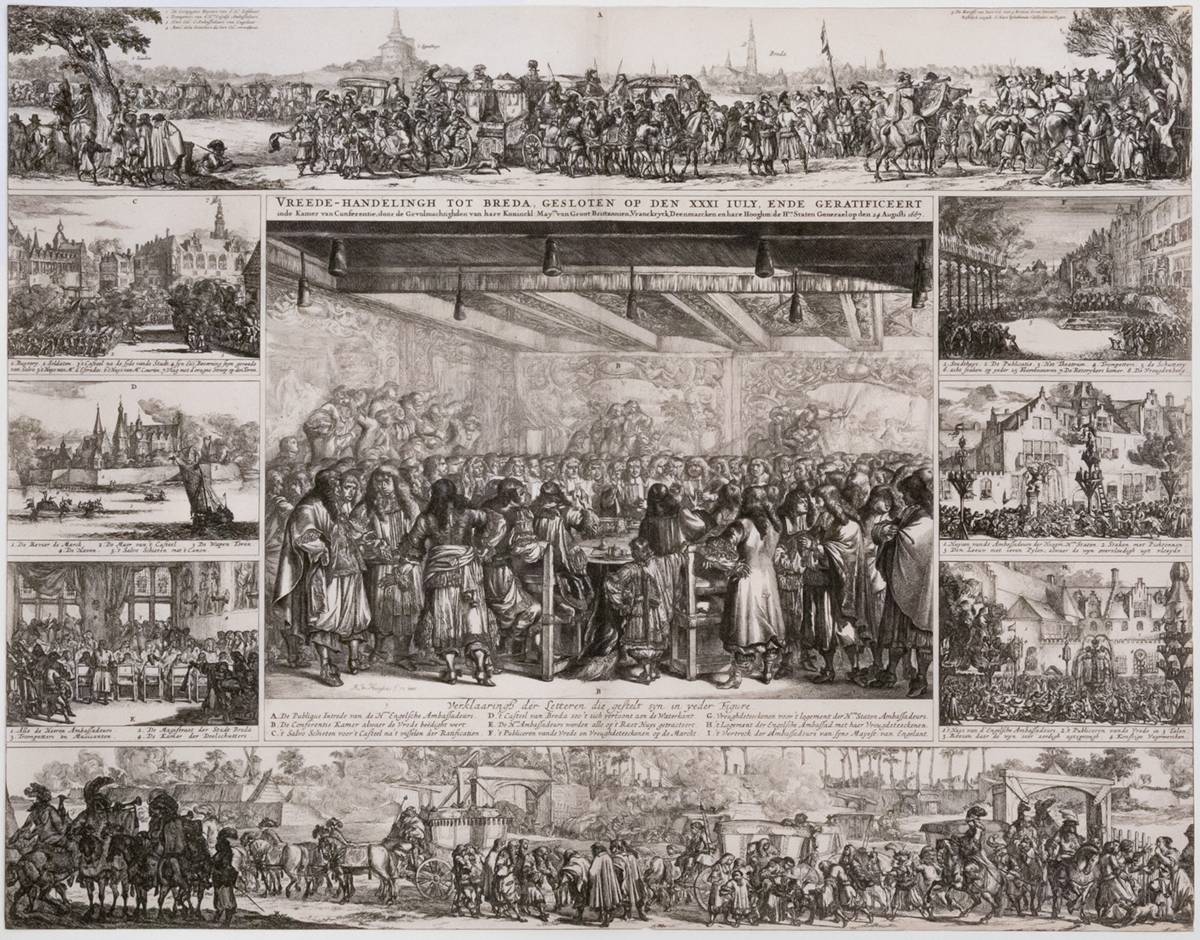

Romeyn de Hooghe (Dutch, 1645–1708), Peace Conference at Breda, 1667, depicted in nine scenes, 1667, Etching, Museum purchase through the John N. Chester Fund, 2019-7-6

One of her goals in curating this exhibit is to challenge and broaden our definition of what art looked like at this time, and perhaps, more importantly, what larger purposes it may have served.

“I’d like audiences to see the 17th-century Netherlands a little differently. People think of the tranquility of Vermeer’s milkmaid and Rembrandt’s windmills, so they can imagine this was a peaceful landscape. Politically, it was a maelstrom. Opposing groups were fighting tooth and nail, sometimes quite violently. I’d like this exhibition to resonate with our political culture and fake news in our own age, and to lead visitors to see how we continue to be persuaded by imagery.”

Warren sees this era’s outpouring of political art as a result of two significant and non-unrelated factors: political unrest and emerging print technologies

“The Netherlands was a republic in a sea of monarchies. It’s why they have this really radical printmaking and image-making a full century before most of their neighbors. There were talented, technologically-savvy printmakers putting tremendous financial and intellectual resources into making political arguments through provocative imagery.”

Romeyn de Hooghe (Dutch, 1645–1708), Marriage of William and Mary, 1677, Etching, Museum purchase through the John N. Chester Fund, 2019-7-7

Maureen Warren considers de Hooghe a “propaganda master” and credits him with inventing a new form of political satire in which stories and characters were so thinly disguised that there would be little question of who or what was being satirized.

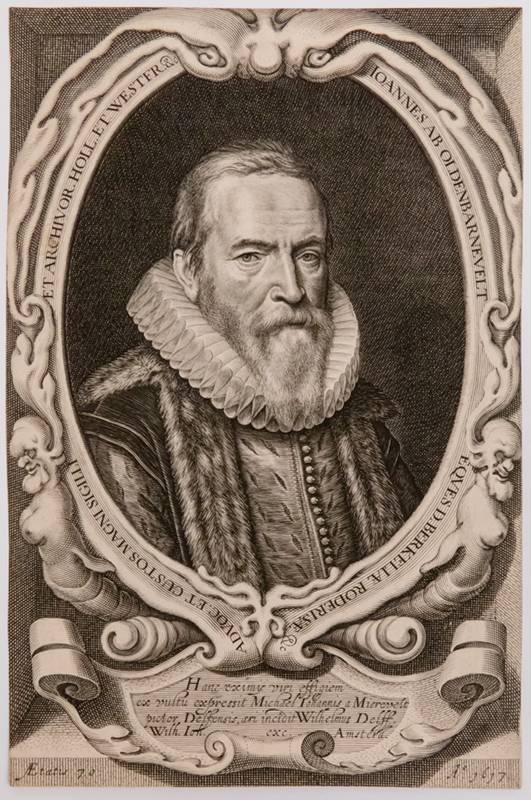

Willem Jacobsz. Delft, (1580–1638) after Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt (1566–1641)

Portrait of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547–1619), 1617, Engraving

Museum purchase through the John N. Chester Fund, L2019.45

The fact that the collection is comprised of prints is significant. Though created by established fine artists, many of these works appeared in text-heavy broadsheets and have therefore considered the provenance of libraries, rather than art museums. Though printed in large numbers and meant for wide public distribution, these types of prints were rarely considered collectible at the time. In order to get these works to KAM, Warren applied to the U. of I.’s John N. Chester Endowment Fund, which supported one-third of the total acquisitions.

Romeyn de Hooghe (Dutch, 1645–1708), Peace Conference at Breda, 1667, depicted in nine scenes, 1667, Etching, Museum purchase through the John N. Chester Fund, 2019-7-6

While examinating how images were used to sell a particular, and often more positive, version of current events, the exhibit will also explore representations of women’s lives, particularly depictions of their independence, as well as images of Dutch naval power, trade, war, and crime.

The exhibition will look at how images were used to put a favorable spin on events and persuade people to believe a certain retelling of history.

Romeyn de Hooghe (Dutch, 1645–1708), Arlequin Deodat et Pamigre Hypochondriaques, ca. 1688, Engraving, letterpress glued on verso, Museum purchase through the John N. Chester Fund, 2019-7-5

Scheduled to open in fall 2021, the provisionally titled “Fake News and Lying Pictures: Political Prints in the Dutch Golden Age” was made possible by a grant from the Getty Foundation which support the exhibition and an accompanying publication through The Paper Project, a funding initiative focused on prints and drawings curatorship in the 21st century. We are incredibly lucky to have such important work happening right here in our community.

And though this means we will have to wait a while to enjoy the results of Warren’s groundbreaking scholarship and inspired curation, I share this preview as a reminder that at their best, museums stand not as monuments to the past, but as discursive sites where current challenges can be placed in broader and more illuminating contexts. So as we continue to drown in fake news and lying pictures up through the 2020 campaign, it might serve us well to channel Maureen Warren’s critical eye and unpack these images carefully.

To keep up with this exciting collection and other news from Krannert Art Museum, follow them on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, or visit their website.

Photos courtesy of Krannert Art Museum