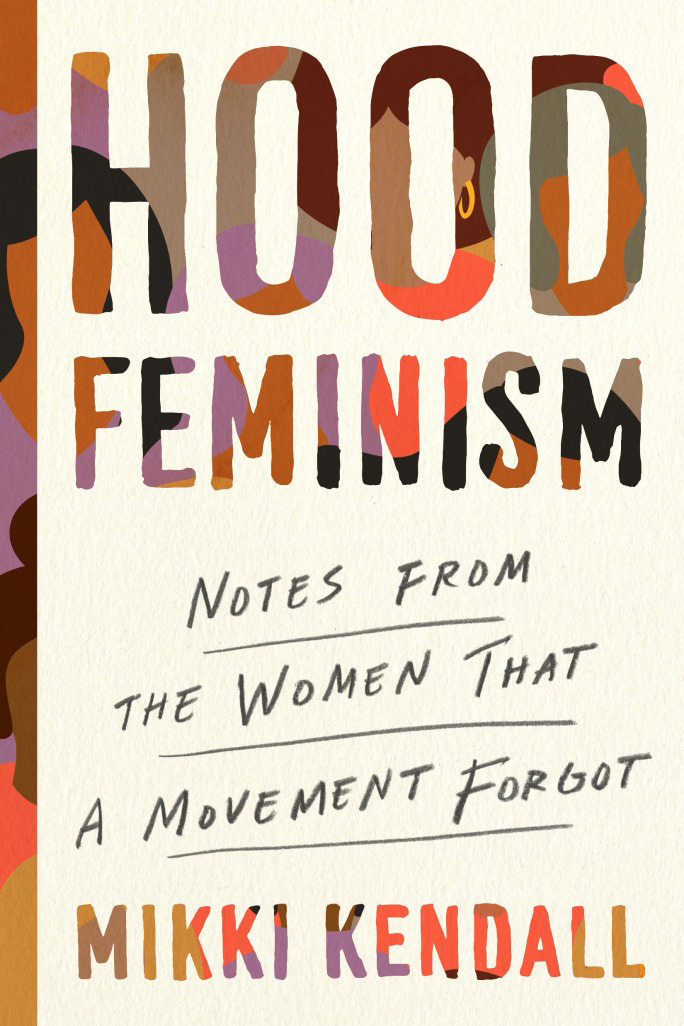

The Literary reached standing-room only and was buzzing with excited conversation long before Kendall began speaking. Every chair, couch, and step-stool was a seat for an enthusiastic reader, waiting for the Q&A with the author to begin. Kendall is the author of both Hood Feminism (Viking, 2020) and the graphic novel Amazons, Abolitionists, and Activists: A Graphic History of Women’s Fight for Their Rights (Ten Speed Press, 2019), but it was Hood Feminism that appeared in the window and in the hands of most of the readers present. An unsold copy of this book had barely to be brought out and placed on a display by watchful staff before it was quickly picked up by a waiting enthusiast to be signed and later read.

A constant question Kendall’s audience seems to have is what inspired her to make Hood Feminism so accessible, which it truly is. It reads unpretentiously and conversationally but seriously, seeking to invite readers in and to give them advice that makes taking action easy. It encourages them to think about what they can do, how they can help, and the kinds of privileges they have that they could leverage to remove systemic barriers in their communities instead of getting caught up in doing activism “perfectly” or feeling like they can’t get started until they can talk the most advanced talk while they’re walking.

Kendall wrote Hood Feminism because she wanted to discuss social issues within feminism that have often been characterized as “divisive” or “hurting the cause.” These naturally include race and class, but also food and housing insecurity, domestic violence, education, ability, reproductive justice, sexual orientation and the insidiousness of respectability politics. Mainstream feminism has an undeniable (and often unhelpful) preoccupation with respectability, and by Kendall’s own description it has had this problem for far longer than she has been writing. Importantly, she does not consider her work to be breaking new ground, but to be bringing an already-long conversation into a more public space where it was previously only happening in private.

She has also been unwilling to write a book that intellectually prices many readers out of engaging with its ideas. In answer to a question from the audience, she described reading statistics that said the average American adult reads at between a seventh and tenth-grade level; further, that opaque, jargon-heavy texts can be generally miserable to read, even for readers who are used to them (to the room’s general agreement). Kendall holds degrees from both UIUC and DePaul, and has necessarily read widely in fields whose literature is packed with jargon, obscure references, and purposefully-difficult writing—she knows whereof she speaks. She wants Hood Feminism to account for both of these factors: to be readable and re-readable by average readers, and to be both enjoyable and inspiring to read and to think about. Judging by the enthusiasm for her book and the diversity of people who came out to hear her speak, she is succeeding.

Much of Hood Feminism is also autobiographical. “I decided a long time ago not to be ashamed,” Kendall explained to her audience before declaring, “Shame is a useless emotion. Once you let shame about the things that happen to you go, then you can see the things for what they are.” Her two favorite chapters, “The Hood Doesn’t Hate Smart People” and “How to Write About Black Women” examine her experiences with the systemic issues that intersect with feminism and the contradictory narratives that can create or try to create feelings of shame in people from marginalized communities. In “The Hood Doesn’t Hate Smart People,” Kendall writes that “It’s no surprise that a narrative of ‘being smart is acting white, so other marginalized people hate you” resonates with a lot of people. After all, it echoes a narrow, stereotypical image of what it means to be Black, to be Latinx, Asian, or Indigenous. It validates the prejudices of adults who remember feeling that they were different, and remember conflating that feeling with ostracism.” (144–5) Such a narrative often plays directly into other narratives of respectability and exceptionalism, where improving one’s circumstances and stabilizing one’s life comes with the added cost of cutting off the individual from their community. Community, to Kendall, is essential, and a strong community that looks after all of its members regardless of how respectable they are or their perceived ability to contribute is evidence of a strong, vital feminism done well.

As a gathering of minds, The Literary did an excellent job of putting together Kendall’s Q&A. In addition to being a superb author, Kendall is also an engaging public speaker who has a natural gift for talking directly and unapologetically to her audience about heavy topics without making the future seem hopeless. She doesn’t sugarcoat the truth—and no one who has read her writing would expect her to—but she also speaks with an infectious optimism. “The world after COVID is the world we have to live in,” she remarked, and Hood Feminism is overflowing with ways that we might all make that world better.

The Literary

122 N Neil St, Champaign

Check out upcoming events here.

Learn more about Mikki Kendall on the author’s website.