No matter what I say about my ability to suspend disbelief or put aside any preconceived notions or biases, it’s much easier said than done. For me, at least, it’s not like flipping a switch; rather, it is a constant internal reminder to forget what you know and accept what you see.

No matter what I say about my ability to suspend disbelief or put aside any preconceived notions or biases, it’s much easier said than done. For me, at least, it’s not like flipping a switch; rather, it is a constant internal reminder to forget what you know and accept what you see.

Which is both apt and ironic, given the subject.

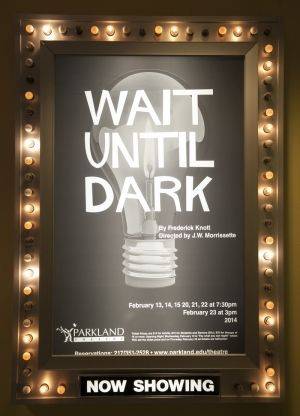

I told myself — as I walked into Parkland College Theatre’s wide, comfortable auditorium — that I would not put my foreknowledge of the play as written ahead of the play being presented. I told myself that I wouldn’t superimpose my fondness for the Terence Young film starring Audrey Hepburn and Alan Arkin on this production. I would do what Edward Albee once recommended, which is to watch a play as if I’d never seen one before.

As it turns out, I needn’t have worried quite so much, because JW Morrissette’s production of Wait Until Dark is a gripping, thoroughly effective experience. For those not familiar with the plot: three criminals converge on a basement apartment in New York in order to find a doll. Two of the conmen are past associates brought together by the third, a mysterious operative called Roat (played by Zachary Ross). The doll has been passed to one of the apartment’s occupants (Sam Hendrix, played by Monty Joyce) via subterfuge, and neither he nor his wife (Susy, played by Cara Maurizi) know how valuable the doll is or where, at the moment, it could be. When Sam leaves town on business, Susy — who is blind as the result of an accident and is still getting used to her new life — becomes the target of the trio’s machinations. Will she see through the con? Can she find the doll? Can Susy outwit the murderous Roat and survive?

The play unfolds cleverly, giving us enough information to wonder how the next bit will play out without ever letting us get too far ahead of the characters. When we meet the play’s first two antagonists, for instance, they don’t know where they are any more than we do. Enter Roat to explain. The necessary exposition is handled artfully. We learn of the plan, and we get a sense of the characters, but there’s never one of those dreadful moments where one character turns to another and says, “We’ve known each other seventeen years, Joe, ever since the bicycle factory caught fire and mangled your leg, causing your wife to leave you.” This is quality suspense writing—the kind that makes you wonder why there aren’t more stage thrillers.

As Mike Talman, the first of the bad men, David Kierski is a cool customer. His is not a showy performance. He doesn’t chew scenery or reach for “interesting choices.” Like Mike the conman, Kierski’s job is to be as normal, as believable as possible, and he anchors the action in such a way that he makes an indelible impression. His Mike manages to be sincere, even when he is lying, and Kierski’s scenes with Maurizi have a lovely low-key tension. We’re fully aware that Mike is pretending to be someone else with Susy, and yet we almost want to believe him. (Also, as a sidenote: Kierski and local actor Mike Prosise should play brothers. Immediately.)

As Carlino, Talman’s partner, David Dillman does wonderful things with the concept of “less is more.” I’ve only seen Mr. Dillman in a handful of roles, and this is my favorite yet. There is genuine menace in Carlino’s threats, and yet he can be invisible at times, blending into the background. All the marks of a good conman.

We see very little of Sam Hendrix in the play, as his removal from the apartment is crucial to the nefarious plan, but Monty Joyce manages to leave his mark on his two brief scenes. We get a sense of Sam as a decent, trusting man who loves his wife and, for that reason, doesn’t cut her any slack. He doesn’t pity his blind wife but rather encourages her to do more on her own. I will admit that, when viewing the film, I always found Sam (as portrayed by Efrem Zimbalist Jr.) to be kind of a dick—patting Susy on the head like she was some kind of spaniel. Not so with Joyce’s Sam, who might be a bit of a hardcase but definitely has a heart.

One of the trickiest roles in a play — and certainly one that can make an experienced theatergoer a little nervous — is that of “the kid.” Knowing that there will be a preteen character in the mix with a cast of grown-ups can make one apprehensive about the tone and, frankly, level of acting one will see. All fears of this kind turned to vapor, however, the moment Karen Hughes (as neighbor Gloria) appeared on stage. Without divulging a lady’s age, I’ll just say that Hughes is older than her character, but she plays the old-soul child with a light touch and a wicked sense of wit. A nuanced performance that folded perfectly into the rest of the batter.

And then there is Susy herself. Oh the shoes Cara Maurizi has to fill in this role. Oh the unfair comparisons. And yet, from her first entrance, Maurizi makes the role her own. Her Susy is such a unique creature, borrowing nothing from other portrayals but rather amplifying (or, when necessary, muting) Maurizi’s own personality to create a sympathetic, smart, and utterly engaging heroine. I have seen Ms. Mauizi in several plays (including a couple where we shared the stage), and I did not realize she was capable of this. This is the kind of role that an actor talks about for years to come as a great opportunity or a big challenge. And Maurizi crushes it. Bravo.

The elements of the production are impeccable. The set, designed by Julie Rundell, is very nearly a character all its own, as Susy’s ability to navigate the space is a constant dramatic device. The space is at once interesting and inconspicuous, detailed but allowed to simply be. The costumes, by Malia Andrus, are similarly noticeable but ignorable. No character seems out of place, yet each character has his or her own identity. The lighting in this play — especially in this play — is a crucial element, and the design (by Susan Summers) is fantastic. In a play about shadowy characters and the loss of sight, darkness is a major player. To that end, the execution of sensitive light adjustments by light board operator Teri Sturdyvin must be commended. This is not an easy gig.

The elements of the production are impeccable. The set, designed by Julie Rundell, is very nearly a character all its own, as Susy’s ability to navigate the space is a constant dramatic device. The space is at once interesting and inconspicuous, detailed but allowed to simply be. The costumes, by Malia Andrus, are similarly noticeable but ignorable. No character seems out of place, yet each character has his or her own identity. The lighting in this play — especially in this play — is a crucial element, and the design (by Susan Summers) is fantastic. In a play about shadowy characters and the loss of sight, darkness is a major player. To that end, the execution of sensitive light adjustments by light board operator Teri Sturdyvin must be commended. This is not an easy gig.

Speaking of the use of darkness and light, I must congratulate director JW Morrissette on a truly thrilling climax to the evening’s orchestrations. I won’t give away what happens or how it happens, but he was right on the money when he told me that it would be something one can only experience in live theatre.

Wait Until Dark is an entertaining nail-biter of a play with a solid, impressive cast. I feel a bit jealous of those who encounter it having never seen the film. I enjoyed the play immensely, but to experience this play moment to moment, as if one had never seen a play before… That is enviable.

Performances continue through this weekend. Do yourself a favor and check out the Parkland website for more information, then make a reservation.