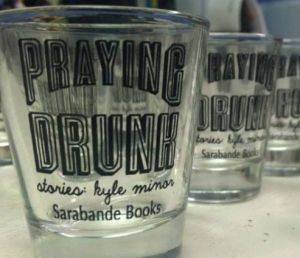

Kyle Minor is a writer. There is plenty of evidence of that, of course. You could do a Google search, or you could pick up one of his books, which include a couple of collections of short fiction called In the Devil’s Territory and Praying Drunk. More evidence can be found in his numerous awards and accolades, including the 2012 Iowa Review Prize for Short Fiction and the Tara M. Kroger Prize for Short Fiction. He was also named one of Random House’s Best New Voices of 2006, and he is a three-time honoree in the Atlantic Monthly contest. And the list goes on. Seriously, do a Google search.

Kyle Minor is a writer. There is plenty of evidence of that, of course. You could do a Google search, or you could pick up one of his books, which include a couple of collections of short fiction called In the Devil’s Territory and Praying Drunk. More evidence can be found in his numerous awards and accolades, including the 2012 Iowa Review Prize for Short Fiction and the Tara M. Kroger Prize for Short Fiction. He was also named one of Random House’s Best New Voices of 2006, and he is a three-time honoree in the Atlantic Monthly contest. And the list goes on. Seriously, do a Google search.

But it takes speaking with the man, even if it’s via email, to understand what a lover of words and letters and ideas he is. Having had such an opportunity, as you’re about to read, I can say with great enthusiasm that we are fortunate to have him reading and speaking at Pygmalion Lit Fest. It will be entertaining; it will be educational; and, above all, and without meaning to sound redundant, it will be literary.

Here’s how our conversation went…

Smile Politely: In your latest book, Praying Drunk, you go against commonly held beliefs about collections of short stories and inform the reader that the stories must be read in order. Why was the order so important for you? Do you often wish you could dictate other aspects of the reader’s experience, like “For the next 20 pages, go to the nearest seedy bar and nurse a beer?”

Kyle Minor: Sure, I wish I could dictate all sorts of readerly behaviors and self-talk, such as: For the next year or seventeen, I will buy twenty-seven copies of this book to give as gifts to all the people closest to me. And I like your idea, too — a book that tells the reader how to read each story. I guess there are books that do that in oneway or another. Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler, with its explicit instructions about reading posture. (“You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought. Let the world around you fade. Best to close the door; the TV is always on in the next room. Tell the others right away, “No, I don’t want to watch TV!” Raise your voice—they won’t hear you otherwise—”I’m reading! I don’t want to be disturbed!” Maybe they haven’t heard you, with all that racket; speak louder, yell: “I’m beginning to read Italo Calvino’s new novel!” Or if you prefer, don’t say anything; just hope they’ll leave you alone. Find the most comfortable position: seated, stretched out, curled up, or lying flat. Flat on your back, on your side, on your stomach. In an easy chair, on the sofa, in the rocker, the deck chair, on the hassock. In the hammock, if you have a hammock. On top of your bed, of course, or in the bed. You can even stand on your hands, head down, in the yoga position. With the book upside down, naturally.”) Or Cheever’s Oh What a Paradise It Seems!, which tells the reader when and where and in what weather to read the book: “This is a story to be read in bed in an old house on a rainy night.”

SP: Speaking of “in bed,” what role, if any, do naps play in your creative process?

Minor: I have an important rule when it comes to naps. If I need one, I try to take one.

SP: I’ve read that some readers report being sad and even broken upon reading your stories. What is it about your writing that elicits such reactions of sadness?

Minor: I can’t speak for any individual reader, but I did know a writer once who said, “No pain in the writer, no pain in the reader.” A small part of me is sad to hear that some of my stories have brought about sadness or brokenness, but a larger part of me thrills at this news, because so many of the stories in these two books deal with characters who are broken, and if that sense of brokenness has been delivered to the reader with a visceral force, then maybe the story is doing its job of offering the reader the opportunity to live, for a little while, a life not one’s own, in its fullness. That’s the goal of most of the stories in these first two books, although Praying Drunk has some other, more playful pleasures (I hope) to go along with the darker pleasures.

SP: How does your experience as a “junior preacher” and background in religion affect your writing?

Minor: It’s always dangerous to conflate the writer and the story’s speaker in these ways, although I have it coming in this case because the book more or less explicitly invites the conflation. I could be coy and say: But so does Tim O’Brien’s The ThingsThey Carried, which reads like a broken memoir, but which also is dedicated to people who never existed except in fiction, and which has an ostensible writer who is very concerned about his daughter—except that Tim O’Brien didn’t have a daughter when he wrote The Things They Carried. My book is probably closer to what passes for facts in some ways than his, but what book is closer to the bone than The Things They Carried? It’s instructive. As William Faulkner wrote to Malcolm Cowley in 1948, “I don’t care much for facts, am not much interested in them; you can’t stand a fact up, you’ve got to prop it up, and when you move to one side a little and look at it from that angle, it’s not thick enough to cast a shadow in that direction.” And yet William Faulkner, who lied about his service in World War I (among other things), taught us through fiction, his liar’s art, more true things about human beings in all their complications and contradictions than any fact writer who ever lived. And all the while, he was drawing upon the things he knew best, the things closest to him, the people of his childhood, the stories he learned from the elders, the things he saw with his own eyes, and he invented out of that bounty Yoknapatawpha County, the greatest literary construction since Gilgamesh or Krishna or Yahweh himself.

SP: The speaker in “The San Diego County Credit Union Poinsettia Bowl Party” displays a great deal of self awareness, both is his resentment of his wife’s requests and his feelings towards his mother. How self-aware would you say you are…?

Minor: Writing fiction for ten or more years forces the issue, I would say. Every day you are confronted by the distance between the story you’ve been telling yourself about your life and the evidence that time and distance and reflection cause you to reexamine. I will say this, in closing: When I finished writing the stories that make up the preponderance of these two books, I was tired of myself and the people so close to the world of my childhood, and I started spending large swaths of summers and even falls and springs in the mountains of rural Ouest Province, Haiti, among people I came to love in different ways than the people I had to love enough to write the first two books. The next two books, novels both, will be set there, but damned if the old people don’t creep in anyway. It turns out my community of origin has been into mischief all over the Western Hemisphere, and indeed the world, and that’s a public trouble to match or exceed what looked at first like a private trouble. As Herman Roth told his boy in The Plot Against America, history is what happens to everyone everywhere, to which I might add, for myself and the people of In the Devil’s Territory and Praying Drunk, at least: Colonialism begins at home.

Check out Minor at Pygmalion Lit Fest on Friday at Buvons in Urbana, starting at 8 p.m.