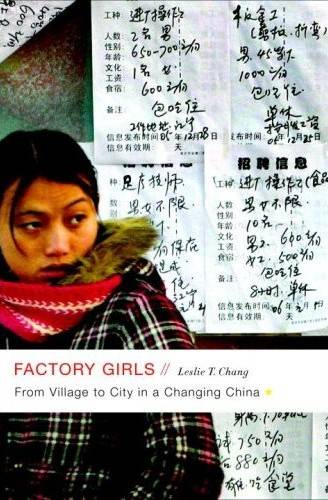

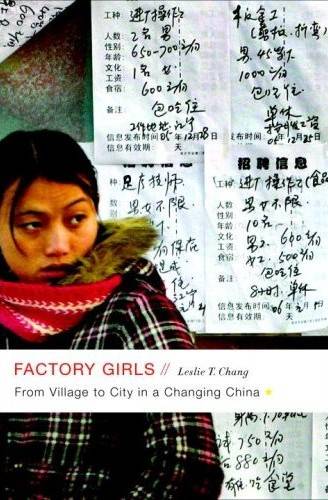

The urban factories of China currently employ around 130-million migrant workers. Many of these workers are the teenage and twenty-something daughters of rural villagers — sons are still valued at home to run the family farm. These young women assemble cell phones, stitch together clothing, and inspect electronic gadgets coming off the assembly line. They are, in large part, the labor force behind China’s booming manufacturing sector. In her book, Factory Girls, former Wall Street Journal correspondent Leslie T. Chang follows a few of these girls through their days in the south China factory city of Dongguan. By so doing, she puts a human face on this exodus from the countryside to the city.

The urban factories of China currently employ around 130-million migrant workers. Many of these workers are the teenage and twenty-something daughters of rural villagers — sons are still valued at home to run the family farm. These young women assemble cell phones, stitch together clothing, and inspect electronic gadgets coming off the assembly line. They are, in large part, the labor force behind China’s booming manufacturing sector. In her book, Factory Girls, former Wall Street Journal correspondent Leslie T. Chang follows a few of these girls through their days in the south China factory city of Dongguan. By so doing, she puts a human face on this exodus from the countryside to the city.

Factory Girls is a book about change. There is, first of all, the backdrop of the sea change in Chinese society from communism to raw capitalism. In one interesting passage, the author compares the rural calendar that has dictated life for generations — when to plant, when to harvest, when to celebrate holidays, etc. — to the business cycle in a giant shoe factory, from the process of taking an order for a batch of sneakers to putting them on the market.

For the girls profiled in this book, change is constant and personal. The author spends months in Dongguan, which has over a million residents, before she actually meets someone from the city. Everyone else is from the country and has had their world change completely in the past few years. Girls leave behind their families in the villages for strangers on assembly lines and in factory dorms. They abandon the traditional Chinese public schools, which focus on learning the history of the communist party, for night classes in commercial city schools where the subjects are intensely practical: English, computer skills, and rudimentary accounting. Girls leap from job to job, trying to improve their pay, status, and condition.

Sometimes, the changes are unexpected. The author interviews more than one girl who has her cell phone stolen, thereby losing the contact information of everyone she knows and forcing her to start over from scratch. For the most part, the girls roll with the changes. They see themselves as being on an adventure, away from home for the first time and surviving on their own.

Chang does a good job examining the personal ambition and individualism that runs rampant in this new world. Some of this seems very familiar to anyone living in the West. One factory girl writes in her diary: “I must exercise my body. To be fat is unacceptable. I must read a lot and practice my writing, so that I can live happily and richly. As for sleep, six hours is enough.” The traditional communist ideology of collective behavior and group thinking has eroded in this economically oriented city. Self-improvement books about positive thinking and hard work leading to wealth and success become bestsellers. Factory girls meeting each other for the first time make snap judgments based on salary and job titles. Income and rank are huge factors on the online dating sites the girls peruse looking for boyfriends or husbands.

Some of the most affecting scenes in this book occur when the author travels with her subjects on vacations back to the girls’ villages. Back home, the girls — who are making substantial financial contributions to their families — gain an elevated status rare in a society that has traditionally stressed Confucian obedience toward older generations. In her village, teenage Min visits older relatives and neighbors, bestowing gifts, turning down or accepting requests for money, and generally basking in her role as worldy provider. During the daytime, she is exempt from family chores. Still, some things between generations haven’t changed completely. Min’s parents disapprove of the relationship between Min’s older sister and her boyfriend because — horrors — he is from a different province, and the sister is sometimes at pains to hide the relationship.

Chang takes an unapologetically personal approach to her examination of this rural migration. In the early pages of the book she writes of the factory girls: “To have a true friend inside the factory was not easy. Girls slept twelve to a room, and in the tight confines of the dorm it was better to keep your secrets. Some girls joined the factory with borrowed ID cards and never told anyone their real names. Some spoke only to those from their home provinces, but that had risks: Gossip traveled quickly from factory to village, and when you went home every auntie and granny would know how much you made and how much you saved and whether you went out with boys.” Writing about her own book on the blog The China Beat, Chang notes that she didn’t start to provide any global background and statistics until around page ten. For the most part, this approach is effective. Chang does not hesitate to put herself into the story, writing accounts of hanging out with the girls in factory dorms, public parks, commercial English classes, and nightclubs, and the reader comes away with a good sense of the personality of the girls and the context of their lives.

However, Chang — in some points — goes too far in including herself. Although raised in America herself, Chang’s parents immigrated from China, and Chang devotes several chapters in her book to exploring her own family’s background and history in the homeland. Chang notes the changes from her father’s China to the current one. For instance, Chang’s father was beaten by his own father for changing his college major without permission, whereas Min, the contemporary teenager Chang profiled, informs her father what is and isn’t fashionable to wear. But overall, this detour does not work well, as there are not enough parallels to Chang’s primary story of the rural migration.

Still, on the whole, Factory Girls is a timely, informative, and moving book that is well worth reading.