This film’s selection for opening night surprised a lot people. I guess Ebert has developed a fondness for it and he has wanted to show it at his festival for 10 years or so. Ebert’s wife, Chaz, admitted at the screening that even she had never finished it because it was just “too weird.”

Sure, Joe is often weird and cheesy at times, but it’s actually pretty good. The humor is subtle at times and ridiculous at others, the way many 90s movies are. Most importantly, the film has a heart that many comedies — and romantic comedies for that matter — lack today.

The studio created a special new digital print for the festival and it looked impeccable on the screen thanks to a $250,000 projector. Director of Photography Stephen Goldenblatt was on hand for the Q&A and discussed filming in actual film versus digital. Film forces you to get it right the first time or not at all, and it’s evident that Goldenblatt was able to do so here. He captures the different styles throughout the film with precision and clarity.

Joe is a relatable film, despite its absurdities. Joe Banks is a hypochondriac who has essentially stopped living and he needs to find inspiration and a reason to exist. Meg Ryan’s portrayal of DeDe /Angelica /Patricia (it’s nice to see Meg Ryan play something other than herself, in two of these roles) help facilitate Joe’s life-change and his soul is revived. It speaks as an awakening to those who need an awakening in his or her life at some point; this film just takes it to the extreme. If you haven’t watched Joe, give it a chance. It’s not like any other film I have seen and that just doesn’t happen often. It’s bizarre and magical and it should leave you with some warmth and, possibly, lift your “brain cloud.” (JS)

Big Fan

Big Fan

I’ve never been a Patton Oswalt fan, and in all truth, it’s probably best that he didn’t show up for the film festival as it is. Maybe you remember, and maybe you don’t, but Mr. Oswalt took to his blog after a tour stop in Champaign back in 2006 at the Highdive and lit up this community like a church.

Here, scroll down and read this piece of shit entry.

Look I am biased. Ward Gollings, one of my best friends and mentors, put this show on, and let me tell you this: what Patton wrote in his blog was a total fucking LIE. Ward is a true pro, and would have never, EVER, encouraged the audience to heckle or interrupt a performance. The request for that came from … wait for it … Oswalt’s fucking agent. Yep. That’s true. Believe me, don’t believe me, it’s irrelevant. But Patton Oswalt wore out his welcome here a while ago, and I am sorry, but I was kind of glad he didn’t show. His excuse was bullshit anyhow. Double scheduling happens, sure — but whatever. You make things happen at the level he is at. I don’t really wanna hear it.

But, I can separate art from personal matters. There are plenty of bands that I’ve been honored to bring through Champaign that I love to pieces, but whose members or crew were huge dicks. Sure, it tainted my feelings towards them a bit, but I will never stop listening to songs by bands that are just really really good.

Same goes here. Big Fan is a great, great movie. I loved it. And it could have been anyone in that lead role, quite honestly. The fact is, it was written so well, and so true to its topic, that it would be hard for anyone who is obsessed with sports, and understands the minutae of poring over things like position matchups and scheduling in a conference season to disagree. The premise of the film here is basic: insane NY Giants fan finds himself in the middle of a mess as a result of trying to get close to his favorite player on said team. What ensues is both hilarious and pathetic; heartbreaking and candid. Parts of the film get tired midway through, but the ending is so brilliant, so perfectly defined, that I instantly forgot all that was starting to bother me about the movie and immediately decided that I’d be watching it again at some point in the future.

Perhaps Ebert had no clue about the ways in which Mr. Oswalt denigrated our community six years ago. Perhaps he did, and didn’t care anyway, because he felt as strongly about the picture as I ended up feeling. No matter. Oswalt didn’t come to the festival, the movie was really good, and he was spared a question by yours truly regarding how he really feels about Champaign. Probably for the best. (SF)

Kinyarwanda

Kinyarwanda

“Violence is expensive, bodies are expensive, and blood is expensive,” director Alrick Brown said after the Ebertfest viewing of Kinyarwanda, explaining one of the reasons why his crew chose not to use much on-screen violence in the film about the 100-day Rwandan genocide. With a $250,000 budget, he said they couldn’t afford helicopters and Hollywood-style explosions, but it’s clear from watching the film that, as the saying goes, sometimes you learn to do more when you have less. The lack of on-screen violence makes this film all the more compelling. In his post-film talk, Brown noted that the sound design included gunshots and barking dogs, setting a tone for the film that included an ever-present feeling of violence.

The filmmakers clearly chose to focus on the human aspect of the 1994 conflict. In a non-sequential patchwork of interconnected personal stories, we meet a remorseful soldier from a killing unit, a hunted Catholic priest, and Jeanne and Patrique, a young couple falling in love, among others. Many stories are real. Most are disturbing. Each explain the agony from both sides of the conflict.

Kinyarwanda is riveting, compelling, and punctuated with just enough humor and forgiveness to leave you feeling hope again at the end. It was the wisest use of 96 minutes I’ve spent all month. (SK)

Terri

Terri

There is something to be said for the fat kid that gets made fun of. It’s a familiar tale. Not one of us who went to public school didn’t have a bud, a pal, a nemesis, a neighbor, who didn’t carry a few extra, and consequently, felt the wrath of the coolest in the class.

Terri plays it up, and then some, leaving its audience to be marred with the anguish of having to be voyeurs and simultaneously, being injected on to his team. Had director Azazel Jacobs not so deftly directed and crafted this film, and had casting not put the inevitably perfect John C. Reilly in the role that it did, Terri might have been a pathetic attempt at a coming-of-age tale.

Instead, it is a really high quality picture. Up there with The Breakfast Club and Karate Kid and Almost Famous? Nah … not there. But still, a totally formidable film, and a sign of things to come from both director and star. John C. Reilly already owns my heart.

The movie’s star, Jacob Wysocki, was on hand to discuss the film, and man oh man oh man, is this fella green behind the ears. Cute, even, in his discussion, the 22-year-old spoke truthfully about the stroke of luck he’d come upon in his casting with role. A community college student just three years removed, the newly slimmed down (but with still some work to do) Wysocki is grateful; he knows just how fateful his life has become, and sees how awesome of a life he is currently living: being flown from film festival to film festival to discuss his genuinely fantastic performance as opposed to being stuck where so many of us were, and still are, to a degree.

That perspective came through in the movie as much as it did in the discussion. And for that, I loved Terri even more after having seen it. (SF)

On Borrowed Time

On Borrowed Time

No one was expecting Roger Ebert to show up to introduce films for the festival, or at least I wasn’t, but Ebert was feeling better on Friday and wouldn’t have missed co-introducing a film about Paul Cox, a filmmaker and one of his friends who has now been featured for three of the 14 years of the festival. The documentary film by David Bradbury is about Cox — a retrospective through his life in filmmaking and his journey through cancer, which required a liver transplant. The idea of the film is that each of us lives on borrowed time, because we never know when things will end.

Apparently, for those who know Cox, the film captures his personality and determination perfectly, a credit to Bradbury to successfully capture a filmmaker on film. Since Cox never cared about making headlines or being in the filmmaking spotlight, the documentary outlines how, throughout the making of his 22 films, he was accused at times of too much realism for things like having too many lepers in a film about lepers. Maybe because of his persuasiveness and commitment to reality, he emboldened unlikely actors of all ages to disrobe on screen.

The documentary, perhaps, was meant to entice me into viewing a few Cox movies, and although I won’t see all 22, I might try to catch a few of Cox’s favorites, Innocence, Vincent, and A Woman’s Tale. (SK)

Wild and Weird

Wild and Weird

As I mentioned in my Ebertfest preview, this is what I looked forward to seeing the most this year. While the Alloy Orchestra wasn’t as active and loud as they were during last year’s Metropolis, they brought seamless accompaniment to the silent shorts this year. It was more about detail and timing this time around, as they played to the variety of styles portrayed in the film selections. Honestly, it helped get me through a couple shorts that I just wanted to end. Here are my favorites from the screening:

The Cameraman’s Revenge (1912) — A stop-animated, detailed story about unfaithful insects. It was one of the longer shorts, I believe, but it felt brisk and action-packed due to its breezy storytelling and the intrigue and suspense built through Alloy’s instruments. The detail in the animation is unmatched here and a triumph for its time. I would have been just as impressed if this was shot today.

The Red Spectre (1907) — A French short full of special effects: disappearing, shrinking, levitating, and setting things ablaze out of thin air, in addition to colored hand-tinting. Alloy was on target the whole time here, their sound mirroring fireballs, puffs of smoke, and the sinister red skeleton devil lurking on screen.

Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906) and Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend: The Pet (1921) — These are stories of a man who over-indulges, which brings him strange, surreal dreams. The former is an interesting look at some stop-motion special effects and a spinning bed that provides all the dizzying and pounding effects that one feels in such a state of inebriation. The latter is an animated dream of a stray pet taken in who has his own indulgence issues. It’s all good fun, the American way.

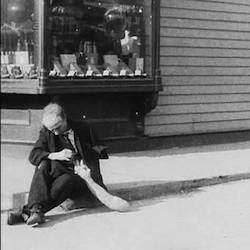

The Thieving Hand (1908) — “No good deed goes unpunished” in this short, in which a one-armed beggar is rewarded with an artificial limb for his honesty in returning a wealthy man’s ring. The hand has a mind of its own, pick-pocketing passersby and leading the man to more trouble than from where he began. Alloy’s capable presence aided the stop-motion animated arm’s comedic journey that brought laughter to the crowd. (JS)

A Separation

A Separation

A Separation can be considered a triumph for Iranian cinema, and for Asghar Farhadi and his family. It won an Academy Award earlier this year, for Best Foreign Language film – a first for Iran in that hyper-competitive category. Farhadi wrote, directed, and produced it, and cast his daughter in one of its most pivotal roles. She mesmerized with her performance, and her father became the first Iranian to win a major Oscar. The film has been the recipient of worldwide acclaim, and much was made of that fact on Friday night at the Virginia Theatre.

At first glance, its subject matter seems difficult to stomach. Newly separated from his wife and forced to hire daily help for his elderly and demented live-in father, a man soon finds himself charged with murdering the caretaker’s unborn child. As we watch him attempt to defend himself while confronting his own crumbling marriage, we’re presented with a tangled mess of heavily complex and conflicting emotions, social and religious trappings, and moral challenges. But, due to the deftness of the film’s ensemble of actors, we are never overwhelmed. The aforementioned Sarina Farhadi is particularly stunning as the 11-year-old daughter caught between her warring parents, and between her desires to draw the truth out of her father and to see him exonerated.

All of these elements make for a rich and powerful movie – one that Roger Ebert himself named the very best of 2011, and one that was a natural to light the Virginia screen. (MC)

Higher Ground

Higher Ground

This movie was the one I wanted to see from the moment that the schedule was released. I’ve enjoyed Vera Farmiga’s work as an actor in the limited times that I’ve seen her perform, but if Roger Ebert says she is even better as a director, I figured: I’d bite.

The fact of the matter here is simple: I was able to relate to this movie in a very significant way, just as I imagine many people can as well. Rooted in the quasi-hippie, leftist, Jesus Freak movement of the late 70s and 80s, the story revolves around the coming of age of newfound Christians, struggling as a young family and learning about what it means to be both good parents and progressive thinkers, all while maintaining a solid understanding of what the Good Book preaches within its pages.

If that last sentence sounded convoluted to you, I join you with a furrowed brow. I was raised in a non-denominational church of a very similar nature (New Covenant Fellowship in Champaign), where the congregation and our elders were just as committed and interesting as the characters in this film. When the movie works, it works well, giving us a harsh glimpse into the power dynamics and tough situations surrounding church plants without much structure or ability to truly understand what it is, exactly, they are trying to preach. When the movie doesn’t work, it tries too hard to be funny, and gives us stupid metaphors about what faith and doubt mean to individuals and how that aspect of the Christian church will never, ever be able to reconcile with its delusional perspective on the history — and future — of this world.

I’d like to tell you that I loved this movie, but I simply didn’t. Perhaps it’s because Robert Duvall drove one so far out of the park with 1997’s The Apostle (watch the whole thing right here) that any attempt to try to bring to life the ins and outs of evangelical Christian life in the modern era might just always fall flat. But I was entertained for most of it, and these days, that’s all I ask from a movie. (SF)

Patang

Patang

Kites. I once dated a girl who left me for a dude who flew kites. His family owned the Iams brand pet food, and sold it off for three billion the year that she flew the coop. I couldn’t help but associate the two.

How is it relevant here? Not in any way — but honestly, we couldn’t get anyone to take the time on a Saturday afternoon to get excited about this feature.

But flying kites? Yeah. It’s really just not that much fun. I am willing to take criticism for it, but get real — we’ve got hover boards in the pipeline. Give it up, people. No one cares. (SF)

Take Shelter

Take Shelter

Just before Take Shelter lit up the screen on Saturday night, Jeff Nichols took the stage alongside the film’s lead, Michael Shannon, to thank the audience, and offer a bit of insight on what proved to be one of the more disturbing films I’ve seen in some time. The film, he said, has come to represent not only what he saw as being a very dark time in his own life, but also, in our country’s history. My annoyance over this bit of context soon gave way as I was introduced to Curtis, a 30-something father and husband who, in the midst of living his own middling version of the American dream, begins to have dreams of a very different sort: danger is on the horizon in the form of some indescribable storm. Dread mounts on dread as Curtis struggles to remain self-aware while simultaneously being seduced by his own ideation. A chasm widens between what Curtis knows and what he understands that ultimately seeps into the audience’s perception of what is real, what is not real, and what is to be feared, and in the process thereof, challenges the audience to empathize with him in some very unexpected ways. (CDC)

Citizen Kane

Citizen Kane

Oh. So you’re a really big Orson Welles fan, are you? Wow. That’s really neat. You must have taken an Introduction to Film class in college, amiright? What a great opportunity you had this Sunday to watch such a profoundly influential American Masterpiece for the second time. Seriously, though, I’ll bet that film class came in handy when the voice of Ebertfest past said something that your professor could’ve maybe possibly disagreed with, prompting you to whisper your emphatic regurgitations into your poor date’s ear with such authority, such assured veracity, that you had to promptly take a bathroom break in order to adjust your fedora. Congratulations on being awesome. (CDC)

—

To men of a very particular age, Orson Welles is best remembered for being the bloated, disembodied voice of the planet-eating robot, Unicron, in Transformers: The Movie. To everyone else, he’s probably best remembered for Citizen Kane, frequently voted one of the top films of all time, including #1 on the AFI’s Top 100 Movies of the 20th Century. The Ebertfest showing of the film with Roger Ebert’s critic’s commentary helps to remind viewers of the reasons for these high ratings. Some people claim this film is sleep-inducingly boring, but for some of us, the incredible visuals and sound will keep us engaged through many, many viewings. Ebert’s commentary helps to cement just why this can be, by focusing on the incredible use of light, sound, and powerful early special effects. Welles came from a background in stage and radio, and it shows in Kane. The film is powerfully punctuated with sound.

Ebert’s commentary draws attention to the articulate use of light and sound to frame and construct scenes and direct the viewer’s attention-or lack thereof-to parts of the screen. The showing in the Virginia, combining the powerful commentary with a big-screen view made this viewer feel the need to watch Citizen Kane yet again. (guest writer Seth M. Spain)