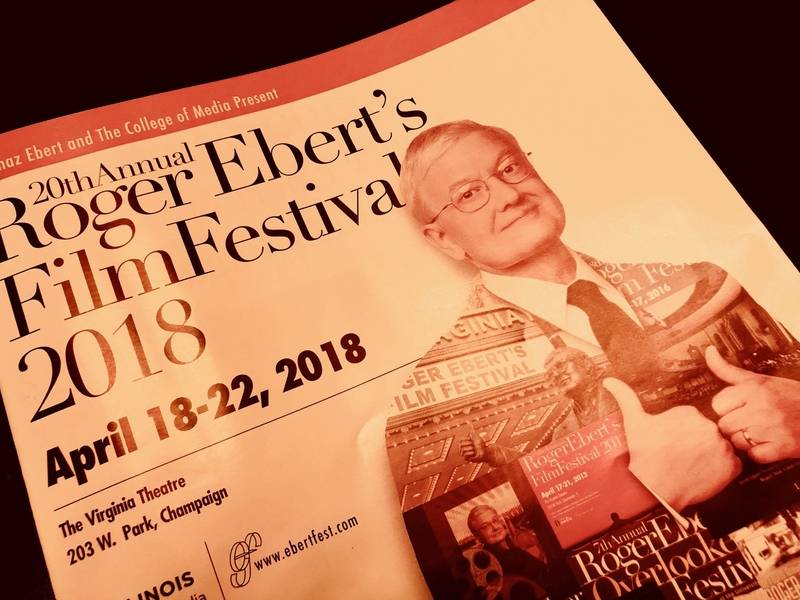

Roger Ebert’s Film Festival has officially been around for two decades, and while many things have changed over the years, one thing remains the same: the festival brings our community together in the name of incredible filmmaking. This year is no different, presenting popular films like Interstellar and The Fugitive alongside critically aclaimed films such as 13th and Columbus. The festival has also garnered a lot of attention beyond CU and seems to be bringing in bigger and bigger names each year. This year Ava DuVernay, Julie Dash, Amma Asante, and Jeff Dowd are just a few of the guests that will join the post film discussions on the Virginia stage. If you can’t make it out to the festival yourself, we’ve got you covered. Our editors and writers are attending all parts of the festival, and we’ll keep you updated on what’s happening right here.

Wednesday

Wednesday

The Fugitive

Folks scurried into The Virginia Theatre and out of the cold for opening night of the 20th anniversary of Ebertfest. Seats on the main floor filled up quickly for the 7 p.m. showing of The Fugitive. Chaz Ebert came out and welcomed the audience, and remarked on the fact that movie going is a community experience that tends to be rare nowadays, when we are all consuming media individually on our devices. In her words, the festival is a part of “healing the world through film.” After hearing from University of Illinois President Timothy Killeen, Dean of the College of Media Wojtek Chodzko-Zajko, and head of the Illinois Film Office Christine Dudley, the movie was introduced by it’s director, Andrew Davis, who choked up a bit in recalling his friendship with Ebert; he even spoke at Ebert’s memorial.

The Fugitive is one of those films that you will watch whenever it’s on TV. I overheard another film-goer say as much, and I could relate. Having the opportunity to view it on the big screen for the first time, and with an audience for the first time, was a thrill, as we collectively applauded it’s magnificent train/bus crash sequence (which was done in one take), and laughed at the expertly inserted humor, mostly delivered through Tommy Lee Jones’ U.S. Marshal Sam Gerard. In his review, Ebert called it a “tense, taut and expert thriller that becomes something more than that, an allegory about an innocent man in a world prepared to crush him.”

In a panel discussion following the film that included Ebert’s former film critic partner Richard Roeper, film critic Scott Mantz, and editor-in-chief of RogerEbert.com Matt Zoller Seitz. Davis recalled realizing in the early screenings of the film that “grandmas might like this movie,” speaking to it’s broad appeal, which was certainly reflected in it’s box office and critical success. Roeper brought attention to the “Chicago-ness” of the film, an aspect which I definitely appreciate as a native Illinoisan. Davis is a Chicagoan, and his love for the city shows throughout the film, from making the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade part of a tense action sequence, to featuring the historic Pullman neighborhood on the city’s South Side, to the final scene in the Chicago Hilton on Michigan Avenue. He also represents Chicago in his casting, sharing how one the cops who grills Richard Kimble after his wife’s murder is a former Chicago police officer, and two members of the famous Cusack clan, John’s brother and father, have small roles. Davis said he wanted a spectrum of humanity in the film, to show the “fabric of Chicago.” There are several familiar faces in the film; Julianne Moore and Jane Lynch each have big parts. Davis joked that Moore is still angry with him after pulling out a love scene with Harrison Ford. Probably the most amazing fact that Davis revealed is that the film took just 52 days of filming and was cut in 7 weeks. Pretty amazing for a film that includes a real train derailment, a parade, helicopter chases, and on location shots in Chicago and North Carolina. Photos by Julie McClure and Patrick Singer.

In a panel discussion following the film that included Ebert’s former film critic partner Richard Roeper, film critic Scott Mantz, and editor-in-chief of RogerEbert.com Matt Zoller Seitz. Davis recalled realizing in the early screenings of the film that “grandmas might like this movie,” speaking to it’s broad appeal, which was certainly reflected in it’s box office and critical success. Roeper brought attention to the “Chicago-ness” of the film, an aspect which I definitely appreciate as a native Illinoisan. Davis is a Chicagoan, and his love for the city shows throughout the film, from making the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade part of a tense action sequence, to featuring the historic Pullman neighborhood on the city’s South Side, to the final scene in the Chicago Hilton on Michigan Avenue. He also represents Chicago in his casting, sharing how one the cops who grills Richard Kimble after his wife’s murder is a former Chicago police officer, and two members of the famous Cusack clan, John’s brother and father, have small roles. Davis said he wanted a spectrum of humanity in the film, to show the “fabric of Chicago.” There are several familiar faces in the film; Julianne Moore and Jane Lynch each have big parts. Davis joked that Moore is still angry with him after pulling out a love scene with Harrison Ford. Probably the most amazing fact that Davis revealed is that the film took just 52 days of filming and was cut in 7 weeks. Pretty amazing for a film that includes a real train derailment, a parade, helicopter chases, and on location shots in Chicago and North Carolina. Photos by Julie McClure and Patrick Singer.

Julie McClure

Thursday

Critical Mass: The Future of Film Criticism

The first official day of the 20th Ebertfest started with a bang at the panel “Critical Mass: The Future of Film Criticism”. Sponsored by Rotten Tomatoes, the panel focused on, as I’m sure one can surmise, the evolution of film criticism as cinema changes. Moderated by writer and critic Claudia Puig, the panel was made up of critics such Rebecca Theodore-Vachon (Entertainment Weekly, NY Times, RogerEbert.com), Matt Fagerholm (RogerEbert.com), Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune), Richard Roeper, Leonard Maltin, and many more. Although filled with humorous quips and snarky jabs at the way younger generations enjoy movies, their discussion offered thoughtful, poignant, and concerned perspectives on the current state of Hollywood and cinema.

Questions presented by Puig ranged from the critics’ views on the means by which cinema is consumed, to how movies on streaming services should be viewed in comparison to theatrical releases, to even the best and worst parts of being a critic. But the most discussion came out of Puig’s question regarding diversity in Hollywood and film criticism, especially the grossly low number of Rotten Tomatoes voting and criticism by women. Or the predominantly male-dominated industry that is film and film criticism. As critics have the tendency to do, they had no objection to talking, and that practically guided the the rest of the panel.

It seems that the draw for the festival is tends to be the films, and the big name guests. But the panels are a wonderful gem in which a true love and appreciation for film can be discussed.

Jarrod Finn

Interstellar

When I saw the list of films that would be shown at this year’s Ebertfest, Interstellar was one that immediately jumped out at me. Not because of how much I enjoyed the film the first time I saw it (IMAX was the route I went, and those of you who did the same know the thrill), but because of how it stuck out as something I wasn’t expecting from the festival. Walking into the Virginia around noontime on Thursday, it started to make a little more sense as Chaz and ebertfest.com’s Brian Tallerico introduced the film. Tallerico described Interstellar as the “biggest film of the festival”, and my thoughts were sure, the special effects are incredible, and the film is massive. A $200 million budget and Christopher Nolan helped make it happen.

I had forgotten how big it made my heart swell watching it, since it has been a few years since I watched the surprisingly-emotional and wrenching film starring Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, and plenty of others. This was Christopher Nolan’s $200M film about love and empathy, which is a central theme of what Roger Ebert was all about. A thrilling exploration through space and time, and so much more scientifically that I won’t begin to attempt to explain, Interstellar‘s spot at this year’s festival made a lot more sense to me as the film was moving forward. The combination of that empathetic component collided with Ebert’s passion for films and humanity, all alongside a R1 University of Illinois — specifically the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA). It came full circle for me, and as the panel that followed it discussed scientific components of the film (discussing other science-based films like 2001 and Star Wars), and how the messages in the film “bypass our brain straight to our gut” as Brand Fortner pointed out. Miguel Alcubierre insight was fascinating — he’s one of the top relativists on this planet.

“Making movies is difficult, but it isn’t rocket science” — Scott Mantz pointed out, he had waited a handful of hours to spill that one. Certainly not, but this film is a marvel — on top of that, mixing love, despair, sadness, and excitement all into 170 minutes made Interstellar the no-brainer I didn’t use my brain quite hard enough to realize fit so well with the programming in 2018. Screencap photo by Patrick Singer, panel photo and photo of Chaz Ebert by Anna Longworth

Patrick Singer

Selena

Following blockbuster Interstellar, the screening of Selena felt intimate and special. A beloved movie about a beloved musician certainly contributed to this mood. But just before the curtains open, and the film began director Gregory Nava mentioned that we would be viewing his own personal print shipped directly from the Academy in Los Angeles. During the subsequent panel, it became quite apparent how close Nava holds the movie to heart.

Moderated by Claudia Puig, the discussion felt more like a conversation between two friends than anything as Nava opened up about how the film was very much a passion project. How as a Mexican-American himself, it became very important to him to truly honor Selena’s importance in the Latino community, especially her importance to the young Latina girls who looked up to her. Nava offered an anecdote about the development of the movie in which he talked about how the studio heads wanted to sensationalize the story of Selena’s death at the hands of her fan club president. He refused to do this. He refused to “spill Selena’s blood on screen.” Instead, he wanted to show the wonderful person and musician that fans cherished.

Moderated by Claudia Puig, the discussion felt more like a conversation between two friends than anything as Nava opened up about how the film was very much a passion project. How as a Mexican-American himself, it became very important to him to truly honor Selena’s importance in the Latino community, especially her importance to the young Latina girls who looked up to her. Nava offered an anecdote about the development of the movie in which he talked about how the studio heads wanted to sensationalize the story of Selena’s death at the hands of her fan club president. He refused to do this. He refused to “spill Selena’s blood on screen.” Instead, he wanted to show the wonderful person and musician that fans cherished.

Also interesting was Nava’s discussion of behind the scenes secrets that perhaps most fans would not know. This mostly centered around the casting of Jennifer Lopez—he cast her out of 10,000 auditions—and how dedicated she was as an actress to study Selena’s tapes and get every little mannerism perfect. Just as interesting was a story Nava telling how one of the more beloved scenes when Selena and her husband Chris Perez elope was nothing but a word for word transcription of the story Perez told him. Nava even shared that Abraham, Selena’s father, was unaware eloping was Selena’s idea until he read the script.

If the Selena panel proves anything, it is that festival goers should come for the movies and stay for the panels. You never know what you will learn. Photos by Jarrod Finn

Jarrod Finn

Belle

When I initially looked at the lineup of films for this year’s festival, I will admit that Belle was one film title that I did not recognize. I didn’t know anything about it, but after briefly looking into each of the films, it was the one I most wanted to see. The summaries I read promised a British period drama with romance and real history, and it delivered.

Visually stunning and emotionally stirring, Belle tells the story of Dido Elizabeth Belle, a woman of mixed race in the 18th century raised to exist somewhere between a “proper” English lady and a slave. It juxtaposes her home life and romances against the issue of the Zong massacre, which was a real case in the 1780s involving the murdering of slaves for insurance money. The film incorporates issues of race, class, and gender on both a personal level and a greater, societal scale. Director Amma Asante said these issues were “layered in” with each new draft of the script in the post film discussion.

One of the points I really appreciated in that discussion was how she explained that it is more than just a love story between a man and a woman. It’s also a love story between Dido and herself, as she gains acceptance and love for herself despite the opinions she encounters and the societal norms of the time. One of the more poignant moments in the film shows Dido in front of a mirror, crying and tearing at her own skin. Asante actually commented that there was some conversation about whether or not that scene should be included in the final version of the film. She insisted that it was necessary in order to see that starting point for Dido and how far she comes in her journey of self acceptance, and that it was a “sanitized” version compared to what they had filmed.

One of the points I really appreciated in that discussion was how she explained that it is more than just a love story between a man and a woman. It’s also a love story between Dido and herself, as she gains acceptance and love for herself despite the opinions she encounters and the societal norms of the time. One of the more poignant moments in the film shows Dido in front of a mirror, crying and tearing at her own skin. Asante actually commented that there was some conversation about whether or not that scene should be included in the final version of the film. She insisted that it was necessary in order to see that starting point for Dido and how far she comes in her journey of self acceptance, and that it was a “sanitized” version compared to what they had filmed.

She also talked about how the film could also be seen as a love story between a father and daughter. Having lost her father just before they went into filming, Asante said a lot of it was a tribute to him. She shared lovely stories about being lectured on the way to school by her father and how his proper language affected the language of Belle (which strikes just the right balance between period and compelling).

The conversation also moved on to the topic of representation in film, particularly for period dramas which, as one audience member put it, tend to ignore the existence of people of color all together. That audience member asked if Asante felt the tides were changing in that regard. She charmingly answered that yes, she felt they were, and she wanted to take some credit for it too. Because of the success of Belle, the gatekeepers of British period drama are finding it difficult to ignore stories of people of color and these stories are fresh new avenues to be admitted into that costume drama world that we love so much. The night ended on a note of hope, that more stories of these hidden figures in history would be shared and adored in the same way that Belle has been. Photos by Kate Fenton

Kate Fenton

Friday

The Alliance for Inclusion and Respect Panel: Challenging Stigma Through the Arts

Day three of Ebertfest started with a couple of panels, the first of which was presented by the Alliance for Inclusion and Respect and focused on “Challenging Stigma Through the Arts.” The panel itself, which included Barry Allen, Julie Dash, Richard Leskosky, Barb Bressner, Joseph Omo-Osagie, Todd Rendelman, and Karen Simms, was a mixture of filmmakers, professors of film, and people using film to address issues of mental health and trauma.

Multiple panels members identified Daughters of the Dust as a movie that they personally identified with, that created new understanding for them about the experiences of others, or that they use in film classes to teach a multitude of different things. Dash, who wrote and directed the film, was able to speak to her experience in creating it. She explained that she grew up as a fan of foreign films, loving the way they took her someplace else, and she wanted to share that experience. After years of studying film in school, she felt that with Daughters of the Dust, their goal wasn’t to create a commercial film. Instead, “we were experimenting.”

Eric Pierson, the moderator of the discussion, asked Dash how she felt Daughters of the Dust has aged in the 25 years since its release. She responded that “The world has changed” since the film originally was released, when it was in some ways a “shock to the system.” But now, people have a new way of accepting stories that are non linear. With a whole new group of people are seeing it for the first time, their reaction is different.

Other panel member discussed the ways they use that film in the classroom—as a bridge into foreign films or as a look into a film that’s “outside the Hollywood pattern.” From there the conversation developed into the importance of using film to find connections. Joseph Omo-Osagie said that he often uses film clips in his Introduction to Psychology class in order to illustrate certain theories psychology or mental illness. He also spoke to the importance of how accessible films can be to students: “If we are not willing to use what young people see on a daily basis, we will lose them.”

The discussion rounded out with thoughts around how visibility creates understanding. It ended in agreement that though progress may be slow, conversations like the one we had are important in that progression. Photos by Kate Fenton

Kate Fenton

Levelling the Playing Field: Hollywood in the time of #MeToo and #TimesUp

The Levelling the Playing Field: Hollywood in the time of #MeToo and #TimesUp panel started with many statistics on the involvement of women in filmmaking throughout history. Interestingly, in 1917, the era of silent films, more women were working in film than now. At that time film was seen as silly and unimportant. Editing movies was the same as sewing in the garment district—a woman’s job. Once filmmaking became important and profitable, “women got moved out.” Now, women are fighting not only to have their stories told on the screen, but to be writers, directors, and people in positions of power in the industry.

The Levelling the Playing Field: Hollywood in the time of #MeToo and #TimesUp panel started with many statistics on the involvement of women in filmmaking throughout history. Interestingly, in 1917, the era of silent films, more women were working in film than now. At that time film was seen as silly and unimportant. Editing movies was the same as sewing in the garment district—a woman’s job. Once filmmaking became important and profitable, “women got moved out.” Now, women are fighting not only to have their stories told on the screen, but to be writers, directors, and people in positions of power in the industry.

But it’s also more than that. As producer Ruth Harnisch spoke about the #TimesUp movement, she said that it’s not just about negative portrayals or a lack of representation. “It’s times up on everything that use to be normal.”

The panel itself included Greg Nava (director of Selena), Ruth Harnisch (exective producer of Columbus), Bob Pulcini (co-director of American Splendor), Julie Dash (writer and director of Daughters of the Dust), Sherri Springer Berman (co-director of American Splendor), Kogonada (writer and director of Columbus), Darrien Gipson (national director of SAFinidie), Andrew Miano (producer of Columbus) and Jeff Dowd (a producer and the inspiration behind “The Dude”). Many of those panel members shared the experiences and struggles they had to get their movies made as women. Bob Pulcini told an anecdote about meeting with a producer who questioned his wife Sherri Springer Berman’s ability to direct. Julie Dash shared that even she, writer and director of Daughters of the Dust, hasn’t been able to make a feature film since; her work since has always been passed on. Sherri Springer Berman spoke to how a movie she worked on was produced by Harvey Weinstein and while she was not personally harassed by him, she was “tortured by the through of what might have happened on my set or to the people around me.”

That inspired her to get involved with the #TimesUp movement, which has a “simple agenda: to create a safe and healthy and equal work environment for all.” While it started with the entertainment business, it’s grown to be more than just a hashtag or stories about famous actresses. #TimesUp has developed a legal fund, which has gained over $26 million just since the first of the year, and is designated to help women who may not be able to afford legal help, who can’t afford to lose work, and who need help.

Near the end of the panel, the conversation came back to films specifically and their impact. Gipson brought up how there are very few women and absolutely no people of color in higher positions of power at major studios or production companies. As such, stories that focus on people of color or women are getting passed on, because there’s still a myth out there that people aren’t interested in that. She told an anecdote about some male white producers who didn’t believe that Black Panther would really do all that well before its release.

The panel closed by looking to the future. Nava said that in his work, he interacts with a lot of “brilliant young female filmmakers” who are “demanding their place at the table.” Hopefully, we’ll hear from them soon. Photo by Kate Fenton

Kate Fenton

Columbus

Columbus focuses on a friendship between a man (John Cho) who is stuck in Columbus, Indiana due to his dying father and a young woman (Hayley Lu Richardson) who chooses to stay there for the sake of her mother. Their honest friendship blossoms out of their shared appreciation for the architecture of the town and their differing attitudes towards their parents. But that short description really does not do justice to all the nuances of the film, which was just stunning to watch on the big screen.

In the post film discussion with director Kogonada, one of the points he spoke to was the idea of absence and its role in the film both on a thematic level and as a technical tool. The story looks at the absence of a parent, whether it be death or the process of leaving home for the first time, but interestingly, the film also uses absence to tell that story. On more than one occasion we are denied seeing the face of who one of the characters is talking to until after the conversation is over. And in one fantastic moment where John Cho’s character pushes the young woman to tell him what moves her about a particular building, the perspective changes. We now see them from inside the building and the sound is cut out—we are denied her answer, though we see it through the window. It was stunning, and I heard a couple of gasps in the audience around me in that moment of silence.

In the post film discussion with director Kogonada, one of the points he spoke to was the idea of absence and its role in the film both on a thematic level and as a technical tool. The story looks at the absence of a parent, whether it be death or the process of leaving home for the first time, but interestingly, the film also uses absence to tell that story. On more than one occasion we are denied seeing the face of who one of the characters is talking to until after the conversation is over. And in one fantastic moment where John Cho’s character pushes the young woman to tell him what moves her about a particular building, the perspective changes. We now see them from inside the building and the sound is cut out—we are denied her answer, though we see it through the window. It was stunning, and I heard a couple of gasps in the audience around me in that moment of silence.

The discussion afterwards also included producers Andrew Miano and Danielle Renfrew Behrens and executive producers Bill and Ruth Harnisch, who spoke to the process of getting the film on its feet. Ruth Harnisch also spoke to the importance of producing films and how she and her husband view themselves as “patrons of art” more than “producers.”

Jeff Dowd actually stood up when they opened up to the audience for questions to comment on the casting of John Cho as the lead, which the group has discussed previous, and to tell a a story about Roger Ebert standing up at Sundance to defend Asian American characters, saying they “have the right to be whoever the hell they want to be. They do not have to ‘represent’ their people.” Dowd also said that Behrens was an example of a real producer, after she explained how she got the sound team on board. Kogonada also commented that he believe it was because she was a woman that she was able to recognize that this story needed to be told, tying it back to the #MeToo and #TimesUp panel that he had participated in earlier. Photos by Kate Fenton

Kate Fenton

Page of Madness

I know it’s slightly shameful to admit, but I am a second semester senior preparing to graduate, and throughout my four years in Champaign-Urbana, I’ve never once attended Ebertfest. Come to think of it, I’ve never actually stepped foot inside the Virginia Theater.

That is (thank goodness) until I was able to attend the showings Page of Madness and American Splendor.

As this post focuses on Page of Madness, the best piece of advice that I can give to future viewers is to devote only a quarter of your attention to the actual plot. While I know that sounds completely counterintuitive, this point was actually recommended to the entire audience by the opening speaker, and after the film finished and the lights came up I think we all understood why.

Page of Madness, which is a 1926 silent film by director Teinosuke Kinugasa, took every element of avant-garde cinematography you could possibly imagine and, amazingly, found a way to incorporate it into a visually captivating piece. The general plot, and as there was no one consensus about what truly happened general is an entirely appropriate description, takes place in an insane asylum where a man works as a custodian to care after his wife, who at the time is a patient. What gets cloudy is exactly why he’s there in the first place, since beyond understanding that he’s trying to do penance for something, you never receive clarity as to what transpired in the past.

But this moment is where my earlier piece of advice comes in handy, because in comparison to the visual effects, and unbelievable live accompaniment by the Alloy Orchestra consisting of musicians Terri Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, the plot’s importance largely fades into the background. I can’t say that I’m now a huge fan of silent film, or that I loved this particular film, but the skill within various camera shots, overlapping scenes, and depictions of intense chaos combined with the Alloy Orchestra’s musical creativity was truly incredible.

Following the film, if you were able to stay there was a brief conversation between two of the Alloy Orchestra members and Ebertfest speakers. First inquiring about how the Orchestra chose Page of Madness (Donahue explained how he’d wanted to work on Page of Madness for years), the questions from there mainly revolved around whether specific music signified a character’s internal or external state, and how they went about constructing music to such an opaque film. To these questions Donahue and Winokur responded that the music was not intended to reflect the interiority/externality of a character, and that during production they tried to simply fit the music into the chaos, instead of pushing on their own narrative. Virginia Theatre photo above by Anna Longworth

Meghan McCoy

American Splendor

For anyone who loves comic books, Paul Giamatti, or just ironic, dry as a bone humor, then American Splendor is a movie made for you.

Beginning in the 1960’s in Cleveland, Ohio, American Splendor tells the life of comic book writer Harvey Pekar, who is also the leading character within his own comics. Pekar is easily one of the most pessimistic, dismal characters you’ve ever come across, but never once did I end up disliking him. Luckily, Pekar’s desire to write his comics in the first place, so that he can show the everyday battles people are always fighting, consistently lends him that superhero quality we all find hard to resist. I think of it as the fierce desire to save everyone and anyone from whatever dangers they’re facing, and while Harvey Pekar never flies off the ground or turns into the Hulk, he does voice the daily concerns, worries, and frustrations people the world over face. To me, that seems harder than almost any Superman stunt.

This film was endearing, beautifully refreshing, genuinely funny, and openly embraced attitudes we all feel but may not always be comfortable showing. In American Splendor grumpiness to outright despair is honestly laid out, and we’re able to sit with it and Harvey, precisely because this pain is not shied away from, but instead given room to breathe. More than anything it was delightful to watch from the casting, cinematography, musical composition, and script writing, and happily this enthusiasm easily transferred over into the after-viewing discussion.

Following the film, we were all incredibly lucky to listen to producer Ted Hope, co-writer and director Shari Springer, and other co-writer and director Robert Pulcini talk about the production process and what working with the real Harvey Pekar was like. Amidst many laughs from the audience and the stage, Springer, Hope, and Pulcini explained how they constructed American Splendor from the physical comic books and old tapes of Pekar on the Dave Letterman Show.

From there, they discussed how they crafted the tone of the film, which again was primarily based off of the comics themselves and the “odd comedy” present in nearly every situation of Pekar’s life. While there were a few more questions, one in which an audience member was extremely impressed by the film’s structure, for most of us I think we left the theater strangely refreshed, and if nothing else, with the sense of another festival day well done. Popcorn photo above by Anna Longworth

Meghan McCoy

Saturday

Lumiere Bros and the Birth of Cinema

I am revealing how much of a history and film geek I am, but the lecture “The Lumiere Bros and the Birth of Cinema” was incredibly fascinating. Given by Richard Neupert, professor of Film Studies at the University of Georgia, the lecture primarily focused on the creation of technology that made cinema as we know it possible.

As Neupert presented, the cinematic camera began with Pere Lumiere, a photographer based in Lyon, France, and his sons. Lumiere had already established himself as a photographer, and unlike many photographers at the time felt motivated to make photography accessible to the general public. Such an impetus drove Lumiere’s growing and increasingly successful company until he saw Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope which could record 30-45 seconds of footage and requires many electrical cords and a large electrical attachment. From there Lumiere and his 17-year-old son created the cinematographe. The rest, as they say, was history.

Beyond the plethora of historical facts, to watch where film has come from was fascinating. To watch the forethought and the creative genius of someone creating an art form that did not exist made my jaw drop. We think that with our modern cameras, editing software, and technology that we have reached the pinnacle of cinema. That contemporary work surpasses all work that comes before it. A lecture such as this one reminds us that we must remember the foundations of art. We cannot truly appreciate where film is now, unless we continue to appreciate that foundations on which cinema was built. Photos by Jarrod Finn

Jarrod Finn

13th

This week has not been a great week to be Black in America. The Starbucks controversy in particular has been a chilling reminder of how tenuous Black folks’ presence can be in spaces where White comfort and security is of primary importance…and this includes Ebertfest. Annually, attending Ebertfest requires that I strap on my psychic armor and give myself the pep talk for screening-while-Black-at-Ebertfest, no matter how many Black films are on the schedule.

On Friday morning, I mentioned my plan to attend the 13th screening to an African American academic. He laughed and and remarked: “Ebertfest, huh? You know, Ebertfest really isn’t for us.” On Saturday morning, I walked from my parking space to the Virginia with an African-American woman who wondered aloud: “I really don’t understand why there aren’t more of us in attendance. I wonder, why don’t the organizers do more outreach? All they would have to do is reach out to Black churches! I can’t tell you how many times I have taken my money out of town because of what we don’t screen or stage here in Champaign-Urbana.” So, it is with these encounters that I arrived at the Saturday morning screening of Ava DuVernay’s 13th —having all of the Sister-Insider-Outsider feelings: UIUC alum, sorority sister of Ava DuVernay, donning my press pass, but roiling inside with a mix of race/gender pride and alienation as I took my photos and prepped my notes. As I watched the film, hot tears streamed down the right side of my face at least every half hour as the film marches us from slavery to mass incarceration and I thought about my own parents who fled Jim Crow Mississippi, my coming of age during the Reagan/Clinton eras, and my own incarcerated relatives and extended family.

As the Q&A opened, the audience was advised that DuVernay’s schedule was extremely tight and that she’d be leaving immediately after. Yet, with the confidence of a woman operating in the fullness of her gifts, DuVernay piloted a rich post-screening discussion divided between her life experiences and influences, her creative priorities as a mediamaker and her hopes for 13th audiences. DuVernay attributed her industry success to her awareness of racial and class disparities at an early age growing up in Compton, CA, her academic interests in Africana Studies, cultivation of a work ethic steeped in collaboration with other women and minorities, opportunities to work with powers like Oprah Winfrey and Netflix who gave her funding and creative freedom, and the support of journalists like Roger Ebert and Carrie Rickey reviewing her early films repeatedly and passionately to help her break through an industry primed to reward young white male filmmakers. The other gift of her remarks was her explanation that 13th is designed to provoke the viewer to consider what each one of us can do — like James Kilgore, who appears in 13th and works on these issues locally in Champaign-Urbana — to dismantle this vast web of mass incarceration.

Unfortunately, despite the rich exchange between DuVernay, Chaz Ebert and acclaimed director/producer Rita Coburn, only one question was allowed from an audience member before DuVernay had to leave for the airport. Ironically, the questions posed to me by fellow African Americans about the relationship between Ebertfest and communities of color locally are perhaps the most pertinent questions I’ve heard this year. Photo by Nicole Anderson-Cobb

Nicole Anderson-Cobb

Daughters of the Dust

After an intensely beautiful and contemplative film about family and one’s roots, Daughters of the Dust director Julie Dash was joined on stage by Chaz Ebert, critic Sheila O’ Malley, and critic/podcaster Sam Vergoso for a charming and engaging discussion.

Serving as an apropos bookend to Ava DuVurnay’s 13th, the panel lead off with a discussion of Dash’s intent to offer a less prevalent depiction of African Americans and African American life. Contrary to what media was portraying at the time of the film’s release her desire was to present a movie about African American life that was not slavery or any other popularized depiction. Rather, she offered a depiction most close to the culture she knew and came from.

As most panels go, there was interesting discussion about the difficulty Dash had finding a interested producers and executives attached to the film. Dash mentioned that she wrote the film in 1988 with the intention of making it a silent film. Executives passed on that and continued to pass because they were not familiar with the history of the culture depicted in the film.

As most panels go, there was interesting discussion about the difficulty Dash had finding a interested producers and executives attached to the film. Dash mentioned that she wrote the film in 1988 with the intention of making it a silent film. Executives passed on that and continued to pass because they were not familiar with the history of the culture depicted in the film.

The highlight of the entire panel was when Sam Vergoso brought up movie’s connection to Beyoncé. Dash offered the following anecdote: On the day Beyoncé released her video Lemonade via HBO, Julie Dash’s website crash and could not be accessed. For a good amount of time she and her assistants could go figure out why. Then she received a call in which a friend implored Dash to watch Lemonade. She did, and turns out that certain scenes in the video replicated images and scenes from Daughters of the Dust. Turns out Beyoncé was heavily influenced by Dash and the film. Photos by Jarrod Finn

Jarrod Finn

Rambling Rose

Rambling Rose after formally being introduced by director Martha Cooldige, was also introduced by Robert Ebert himself, in a short pre-movie clip from At the Movies in which Ebert and Siskel discuss the film, which is told through the point of view of Buddy as he looks back on his young adult life when a beautiful and sensual woman named Rose came to live with them. The film itself is filled with as much love and life as the titular character.

I knew the story addressed sexuality, but I was surprised by the honest way in which it illustrated how Rose, in all of her sexual exploits, was actually looking for love. Because of her past, sex was the only way she knew how to get it. I was also surprised by just how funny it was. I so enjoyed being able to literally laugh out loud with hundreds of other people at simple and subtle moments of the film.

The post film discussion with director Martha Coolidge started with discussing the long process of getting this film on its feet. It took seven years for her as the director and over seventeen for the writer Calder Willingham. She said she changed very little of Willingham’s work, adding only one scene—the scene between the mother and father in bed, who get into a small squabble before eventually making love. Coolidge described how she felt that scene was necessary to seeing “what they had that was a flaw and what they had that was going to get them through it.”

The post film discussion with director Martha Coolidge started with discussing the long process of getting this film on its feet. It took seven years for her as the director and over seventeen for the writer Calder Willingham. She said she changed very little of Willingham’s work, adding only one scene—the scene between the mother and father in bed, who get into a small squabble before eventually making love. Coolidge described how she felt that scene was necessary to seeing “what they had that was a flaw and what they had that was going to get them through it.”

Prompted by an audience member, Coolidge also spoke about the process of filming the climactic moment in which Mother (played by Diane Ladd) defends Rose from two white men deciding what is best for her body (an infuriating moment, believe me). That scene, in which Duvall’s character changes his mind, was shot over three different days and Coolidge insisted on shooting Duvall first, despite Ladd’s requests. She said it took him one take. Meanwhile Ladd was so tense about the scene, Coolidge thought it best to keep trying and pushing her, until she relaxed into it a bit more: “I felt she’d be better with more time, and she was.”

Rambling Rose was beautiful and hysterical and a wonderful ending to my first experience with Ebertfest. Photos by Kate Fenton

Kate Fenton

The Big Lebowski

It’s fitting that EbertFest chose to celebrate its 20th annual festival with a film like The Big Lebowski, perhaps the greatest “cult classic” in the modern era. It lends itself to the festival’s first intentions, which was to bring new eyes to “overlooked” films as far as Roger Ebert was concerned. The film itself is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, as well.

This was the Coen Brothers’ first film release after their sleeper hit Fargo, which set the bar higher than ever for the irreverent duo from Minnesota. As special guest Jeff “The Dude” Dowd explained before the beginning of the movie on a full house on Saturday night, The Big Lebowski offers almost no arc for its characters. No one comes to any sort of grand realization about how they might change, or improve. Nothing really happens, outside of everyone simply accepting their fate amidst a complicated, and sad, set of awkward scenarios fueled by pot smoke, greed, frustration, PTSD, and Creedence Clearwater Revival.

It was a lively audience, and when Dowd asked the audience how many of the crowd hadn’t seen the film, a surprising number of hands shot into the air. When he asked how many had never seen it in a theater, it was 5-1, easily.

When this movie came out, it was, indeed, overlooked. It had a lot of recognition from the critics, having premiered at Sundance and because of the Coen Brothers’ new found fame, the studio took out a good amount of pre-publicity on it prior to its theatrical release.

But this isn’t a movie for the average filmgoer. It’s always been a slow burn. When the movie became available on VHS (and DVD to a small extent), its popularity began to grow via word of mouth and in early internet chat rooms and movie sites. Every viewing offered its fans a new easter egg, a new quote, a new reference, and a new way to approach the caper.

That Nate Kohn and Chaz Ebert would select this film as its Saturday “late” night film is a showcase of the fact that the two of them still recognize and appreciate the original intentions of this event. It is a celebrated movie in so many ways now, having spawned festivals worldwide, tribute cafes in places you’d least expect, and an ever-growing fanbase of “Achievers” who consider themselves fluent in the language of Lebowski.

Seeing it on the big screen with 1500 other people was something that won’t happen often, and that’s what makes this film festival so special. Photo by Seth Fein

Seth Fein

__________________________________________________________________________

For more information on Ebertfest 2018, click here.

Header photo by Patrick Singer.

Wednesday

Wednesday