“For never was a story of more woe/Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.”

This line from Prince Escalus, the last in Shakespeare’s iconic tragedy Romeo and Juliet, lends a definite air of finality and closure to the scene as the curtain falls. For most readers and playgoers, this marks the end of the story: the lovers are dead and the families reconciled by their loss, bringing some solace to their sad fates.

But what happens to everyone else?

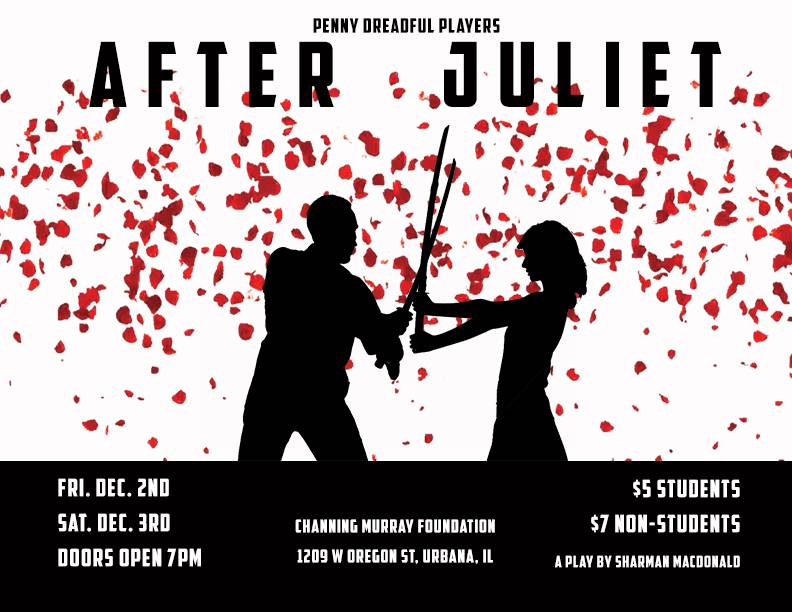

Enter the Penny Dreadful Players’ upcoming production of After Juliet. Set in the aftermath of the original play, After Juliet explores the effects of Romeo and Juliet’s deaths on the families who survived them, and particularly on the young Capulets. Surrounded by a still-raging power struggle between the families and subject to the machinations of the silently ominous Drummer, the teenage characters weave a tangled web of grudges, schemes, and unrequited affections as they progress through a day that will culminate in the election of their new leader.

Katelynn Shennett leads the cast as Rosaline, Juliet’s cousin and the previous object of Romeo’s affections. Rosaline opens the play with the revelation that she had rejected Romeo at the beginning of the original play only because she was playing hard to get, and now resents having lost him — first to Juliet, and then to death. Her grief and bitterness at Romeo’s loss set the tone for the rest of the production, wherein the rest of the characters react to the lovers’ deaths. Some cope with their loss through fits of sadness or rage; others are entirely apathetic, or are simply more concerned with the living than the dead.

The dichotomy between the characters’ responses to Romeo and Juliet’s deaths constitutes just one of the several sets of opposing themes in After Juliet. The production is an amalgamation of opposites, pitting against each other war and peace, life and death, and, perhaps most imperatively in Penny Dreadful’s production, fate and autonomy.

Fate in After Juliet is embodied by the Drummer, played by Logan Weeter. A brooding, unspeaking entity, he lurks in the background throughout the show, alternately observing and directing the events of the play, either by influencing the other characters’ interactions or by controlling their bodies like a ghostly puppeteer. With one notable exception, he and his manipulations go unseen by the rest of the characters, except in certain moments of particularly intrusive intervention. However, though the characters cannot see him, they all seem able to hear his drum as he sends them marching down the path of fate.

Though the Drummer weaves his tangled web of schemes and subplots, the characters within it are not mindless drones subject to his whims. From their interactions emerge a vibrant and varied cast, each with their own motives, wishes, grudges, and angsts; each either accepting the Drummer’s imperious rule or fighting against it. Brittney McHugh delivers a stellar performance as Bianca, the notable exception who, despite being fully aware of fate’s contrivances, often lacks the agency to resist them. On the more manipulable end of the spectrum are Lorenzo (Michelle Lee) and Gianni (Ye Qian [Moody] Wu), two vapid and suggestible characters whose incapability to think independently of one another makes them easy prey for the Drummer’s tune.

The characters’ places on this spectrum of pawns and free agents are visually denoted by their costumes; those characters most subject to the whims of fate are garbed in doublets and vests reminiscent of traditional Shakespearian costumes, while the independent characters wear distinctly modern clothing. The juxtaposition of costuming, along with the use of swords as weapons and the implicit presence of a loudspeaker, gives the production an air of timelessness. The overlapping scenes, characters’ freezing and reanimation, and fluidity of the production root this timelessness within the world of the play itself.

While the dichotomy of themes present throughout the production is one of its greatest sources of meaning, their presentation sometimes seems a bit heavy-handed, largely as a result of the text itself. Most characters are rooted solidly in one camp or the other on every issue, leaving little room for a gray moral area, while the Drummer’s reliance on body language, in combination with his fixed position, limits his ability to communicate his motivation and places him in danger of seeming causelessly antagonistic. Still, the actors find room for nuance within the confines of their roles, creating believable and intriguing characters through their interpretations. Ultimately, the liveliness, vibrancy, and believability that After Juliet’s cast brings to their roles are among the greatest strengths of the production.

After Juliet will run at the Channing Murray Foundation for two nights only. It opens tonight, Friday, December 2nd at 7 p.m., with a second performance on Saturday, December 3rd at the same time. Tickets are $5 for University students and $7 for non-students.